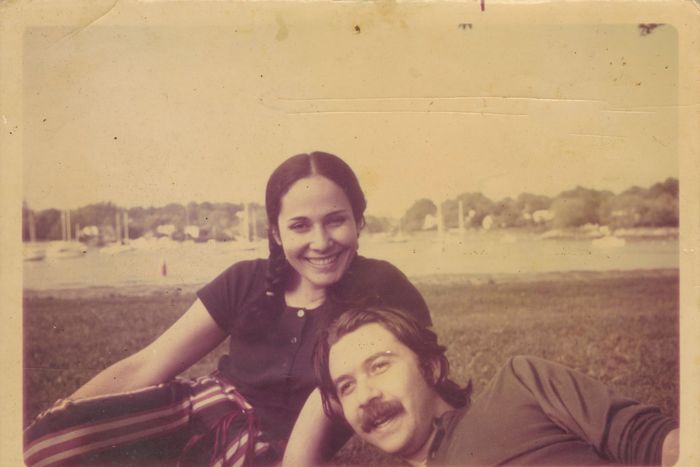

In 1968, artist Anna Maria Maiolino moved to New York from Rio de Janeiro with her husband, Rubens Gerchman, and their two children. Gerchman, an artist, too, had won a grant, and she accompanied him north for the adventure. She’d had a career in Brazil making fabric sculptures and woodcut prints, but in New York, she felt frustrated. She found herself isolated by language — she didn’t know English well — and distracted by domestic responsibilities.

“New York was a very tough city for two artists with children,” Maiolino tells me, switching between Italian, Portuguese, and English. But the whole time she was here, she drew. It was her outlet, and, looking back, her salvation. Her fellow Brazilian expat artist, Hélio Oiticica, suggested she carry a notebook to channel her thoughts. “He reminded me to take up the sketchbook I had begun working on before leaving Rio,” she remembers. “I was motivated to use the notebook because I was already predicting the difficulty of transferring my work to New York.”

On November 14, she opens “Errância Poética (Poetic Wanderings),” an exhibition at Hauser & Wirth in Chelsea, which includes 40 drawings she made in a sketchbook during her New York sojourn, some of which are pictured here. The 76-year-old has the soothing, yet self-assured vibe of an Italian grandmother (she would later insist I ask more questions). “I was surprised when the gallery asked me to turn the drawings into a book and exhibit them because they are so personal and modest,” she says.

She and her family lived in New York for less than three years — first on West 72nd street and later on the Bowery, in a third-floor loft across from where the New Museum stands today. But the city left a lasting impact on her. Upon return to Brazil, she left Gerchman, reclaimed her career, and never gave it up. “The divorce and my return to Brazil came out of my need to be able to do my work, which was difficult for me in New York, in addition to having to take care of my children,” she reveals. “And added was the fact that we were living the well-known crisis of seven years of marriage!”

Over the next five decades, she amassed an oeuvre not restricted by any one language or medium, spanning her introspective and arresting drawings, sculptures, prints, and films.

Hauser & Wirth supports the exhibition with a book, including 72 drawings and Maiolino’s writing on her New York days. “We still have one year more here before returning to Brazil. I wonder why I like this city and what motivates me to remain in this extremely tiring situation, ” she writes.

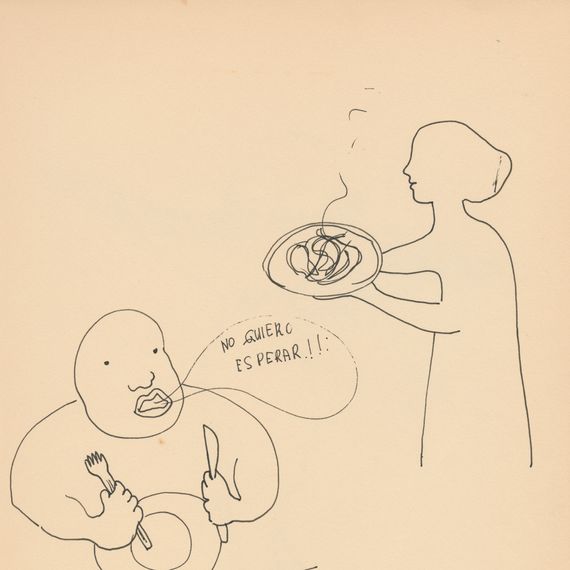

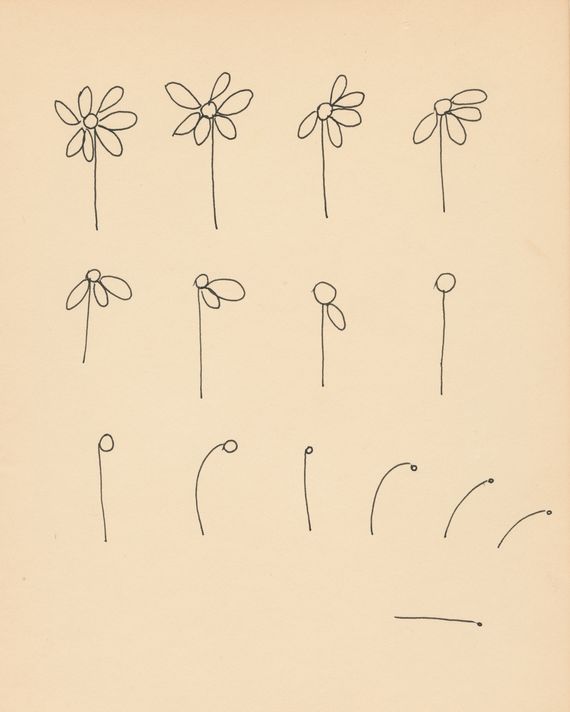

Gracing the book’s cover is an image of a delicate flower gradually losing its petals. A rush of heartache and resilience pervades the drawings, whether Maiolino inserts her figures into sensual domestic scenarios or street scenes. Looking both ethereal and sturdy, her figures are demure, caught in in-between moments. The subtle elegance of her lines suggests fluidity, a sense of evanescence like time itself. In rare occasions, scribbles of words appear. “Rosita, tu me matas (Little rose, you kill me),” a caterpillar says to a rose.

Maiolino’s family had initially migrated to Venezuela from Scalea, Italy, in 1954, but before she became fluent in Spanish, they moved to Brazil in 1960, where she had to learn Portuguese. And while she knew some English when she moved to New York, it wasn’t enough for her to communicate easily. As she recalls it, at the time in New York, Spanish and Italian were looked down on for being immigrant languages. Even their native speakers avoided using them. Among Latin American artists, Maiolino was the Italian, and a woman whose role was to housekeep.

In New York, Maiolino found work at a textile-printing workshop while fulfilling her domestic duties. Her lack of English and limited social circle made her feel isolated, but drawing helped her express herself. She found her missing words through winding lines.

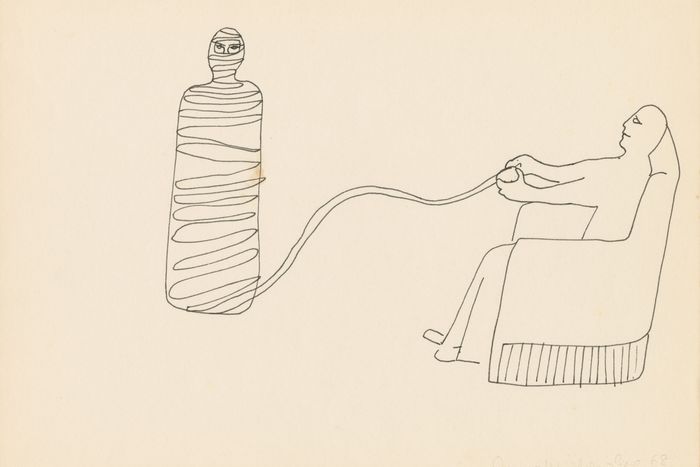

The last figurative work she had created before moving to New York was a 1967 woodcut print of two simply drawn ghostly figures sharing a speech bubble that yells out her name in all caps: ANNA. In her sketchbook, we get a sense of her delirious desire to make art as a woman and mother, and the internal conflicts it presented. A mummylike figure is wrapped around a twirling fabric, held by another person sitting on a couch. Another work shows an enormous roll of paper surrounding a figure, almost like a suffocating blanket. Is she the mummified figure entangled by her husband?

“These are my humble interpretations of New York, not about specific moments or people,” she explains, looking on at her drawings with affection as art handlers arrange them in the gallery with blue-chip meticulousness. For her, they are not only artworks, but old friends, the witnesses of a past life. “I am ready to let the drawings go to a new home with this exhibition, but I will keep six of them for my children and grandson,” Maiolino says. “I just don’t know which ones, yet.”