Nobody likes to be the sibling also-ran, the middling middle child, while big sister or little brother hogs the spotlight. But just as Solange proved herself to be more than just Beyoncé’s little sister with A Seat at the Table, three lesser-known sibs of famous artists are now finally getting their due — albeit posthumously. Right now, there are three exhibitions going on that spotlight the other artists in the families of Georgia O’Keeffe, Marcel Duchamp, and Balthus.

The O’Keeffe Sisters

It turns out Georgia O’Keeffe had a lot to do with why you’ve likely never heard of her little sister Ida. According to Sue Canterbury, a curator at the Dallas Museum of Art, where Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow is on view until February 24, the “mother of modernism” wanted to be the only big-name O’Keeffe and took many steps to keep it that way. Two of Georgia’s six siblings, Catherine and Ida, were also exhibiting artists, but Georgia asked them to stop their practices in the 1930s. She threatened in a letter that she would tear Catherine’s pictures to pieces.

While both Georgia and Ida scraped by, teaching art in various locations throughout the 1910s, Georgia was discovered by the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz in 1918 and brought into the luminous, male-dominated art world in New York City (an opportunity that Canterbury says was unavailable to “99.9999 percent of all the other women artists of the time”). And as that Brooklyn Museum show last year made clear, she worked hard at her brand, and it worked for her. Ida, on the other hand, did not start her painting career until 1932, in the midst of the Depression, after she finished her MFA at Columbia University. Georgia and Ida shared many of the same teachers, art-world friends, and interests, and these influences are apparent in their approaches to surfaces, color, and abstraction techniques. To Georgia’s “disgust,” Ida continued painting even when Georgia asked her explicitly to stop, and so the sisters, who were once close, became estranged. We can’t help but wonder: If Ida had had the same support, space, and time that Georgia did to develop her work, what would have happened?

“It’s the story of an artist who could have been more, had the opportunity been there, it’s a story of the sisters, it’s a story of the situation for women artists in general at that period in time, and it’s also a story about how Georgia created her own myth,” Canterbury says.

She also notes that viewers who have had a sibling who “always got their way” tend to really respond Ida’s work.

The Duchamp Siblings

The Duchamp brothers were more supportive of one another and they often collaborated. Though Marcel Duchamp became the most world-renowned of his six siblings, four of them went on to become artists, often exhibiting together and using each other as models and subjects. Matthew Affron, co-curator of The Duchamp Family at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, on view through August 2019, emphasizes that this show is hardly the first exhibition to juxtapose the other family members’ talents. Marcel’s older brothers were exhibiting artists in France: Jacques Villon was a printmaker and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, a sculptor. Suzanne Duchamp was closest in age to Marcel and they shared a flair for the avant-garde, often exhibiting together in the ’50s and ’60s. Like Marcel, Suzanne and her husband, the abstract painter Jean Crotti, worked with glass and other non-traditional materials mixed with oil paint and went on to form a sub-group of the Dada movement called Tabu.

“When these people first burst on the scene just before and after WWI, they were considered really together, connected to one another through networks as part of the cutting edge,” says Affron. “That’s a story that gets lost when one member of the family ascends to the kind of worldwide fame that Marcel now has.”

Balthus and his Brother, Pierre

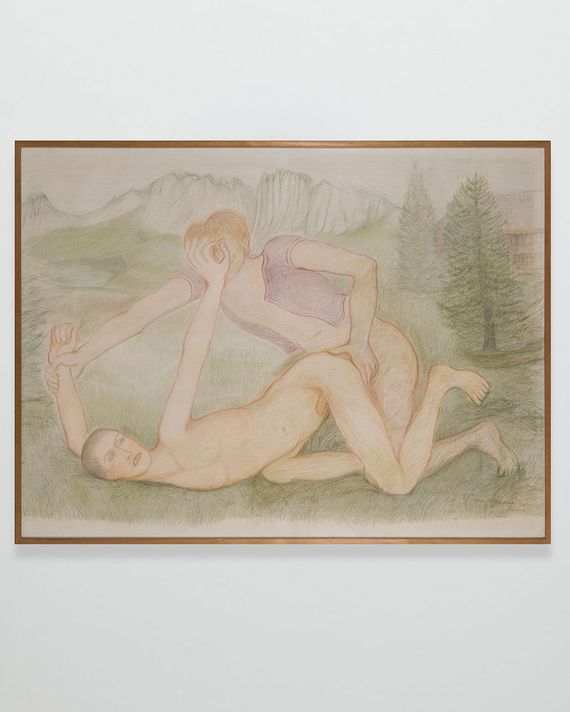

Balthus — whose voyeuristic 1938 painting, Thérèse Dreaming, at the Met, caused a controversy last year — had an older brother who was also an artist, and also, it seems, a bit of a perv. Pierre Klossowski was born in Paris in 1905 (three years before Balthus) to artist parents, and he went on to produce many mannerist-inspired works exploring themes of homoeroticism and sadomasochism. He was “more intellectual,” than his brother Balthus, according to Alexander Hertling, gallerist at Balice Hertling in Paris, where Klossowski’s work is currently on view. While Balthus “enjoyed the social status that he had obtained with his success and enjoyed the company of many famous, rich, and beautiful people,” Hertling says, “Klossowksi wrote important books.” He translated many of Nietzsche’s works and was a specialist — okay, maybe this isn’t surprising — in the work of the Marquis de Sade.

Two of Klossowki’s drawings are currently on view at Balice Hertling through January 2019, as part of an exhibition titled Byrd Hammond Klossowski Olowska, featuring other figurative painters who explore violence from a psychological point of view. The Klossowski drawings, Hermaphrodite of the Alps (1985) and Au Miroir Révélateur (1985), depict sexualized scenarios of Sadist decadence, combining techniques of Italian mannerism with surrealism. Their pastel coloring belies the fact that their subject matter is a little startling, especially in our post-#MeToo era.