As photographer Omar Victor Diop eases into his seat at the oceanside restaurant Le Ngor, it is evident he is happy to be back in Dakar, happy to be back home. He orders a bottle of Flag, the local beer, and sits silently, a little bit regally, listening to the waves roll in, the water keeping his attention. “I like how at this time of day the sun makes the water look silver,” he says, and after a beat he adds, almost like he didn’t want to say it out loud, “I should come here more often. You kind of take it for granted.”

It stands to reason that Diop doesn’t get back here as often as he would like. When we meet, the 38-year-old self-taught photographer has just returned from Paris Photo, the International Fine Art Photography Fair, and the closing of his exhibition, “Liberty: A Universal Chronology of Black Protest/Diaspora” at Autograph, in London.

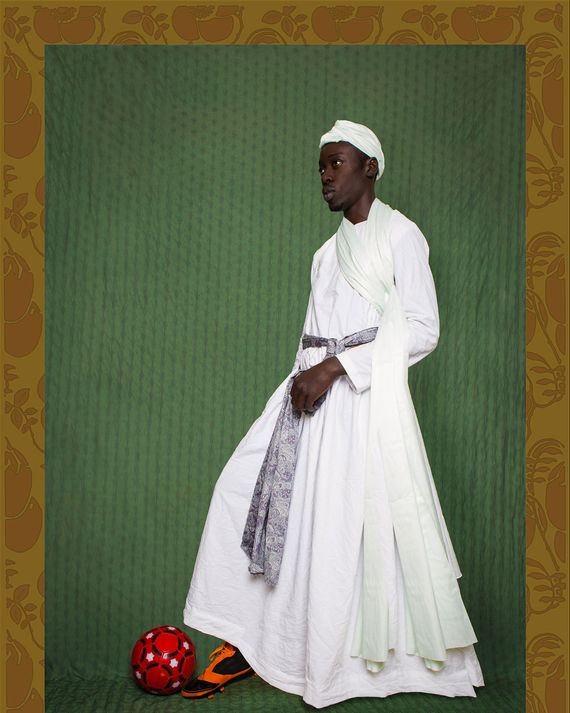

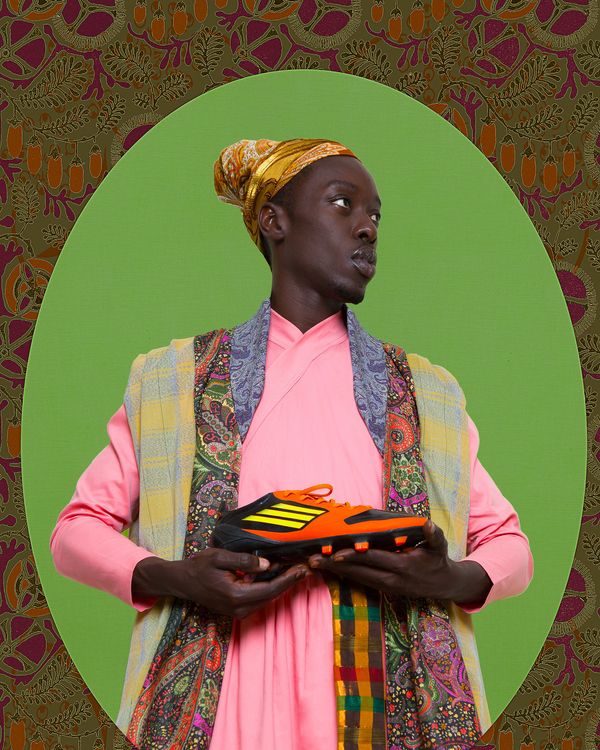

In “Liberty,” he looks at the history of black revolt from the African railway workers and Jamaican Maroons to the Black Panthers and Selma, Alabama, capturing a sense of humanity, survival, and the capacity to persevere. As for the “Diaspora” part of the exhibition, Diop, again, looks at history, highlighting notable African and African-Americans and their impact on European history. Though he photographs himself, these aren’t self-portraits. For him these characters are merely using his body.

Diop glances back at the ocean. “At certain times of the year you can see dolphins jumping in the distance,” he says, as if finally ready to talk. “Yes, I need to come here more often.”

As recently as 2010 you were working in finance and corporate communications. Back then, did you think you’d ever find your footing in the art world?

No. I wasn’t sure it would happen at all. It started with a sabbatical [from my job]. I decided to take a year off because I thought I was in a nice spot, where I could make some money doing advertising and travel for a bit. It was an artistic adventure. But for me, [I thought] at some point it would fade away and I would have to go back to corporate life. But it kept growing and I’m thankful for that. I feel fortunate that I am among the few African and African-based artists that can live on art sales and a couple of projects every year.

Finance is kind of a “good son” profession. Was photography something that you were doing during your corporate life as a hobby?

No. My main trigger is frustration. It has always been. Seeing something, being attracted to it, and realizing that it might be too late. “Oh, I wish, but I can’t.” It always starts with that, but at some point there is always this defining moment where I’m like, “Wait. Who said I can’t?” That’s how it started with photography. In 2010 I bought a camera. It was a very basic Nikon camera. You know the type of SLR cameras that are sold to people to give them the impression that they have a serious camera, but it wasn’t that at all. I had no studio equipment. I just had this tiny camera but it gave me enough megapixels to have something that could be printed. The first time I saw my work printed it was at an exhibition and I was blown away.

In Dakar?

No. At the Rencontres de Bamako [in 2011, also known as the Bamako Biennale]. It was my first exhibition ever, ever. I dropped that envelope off [for consideration] with little prints, cheap prints and I was like, “Okay. I did it at least.” But I forgot about it, then months after I received the email. I thought it was a bad joke from one of my friends, but it was real. They took care of all the logistics and the printing. Basically, I arrived one hour before the opening and I saw the pictures. Yeah. That was a moment. So, the stages for me are: frustration, I challenge the situation, then somehow, most of the time, it happens. In this particular case of photography, it is way beyond what I expected. I’m grateful.

You’ve had a steady rise, internationally. A rise that many artists, in general would appreciate, let alone a self-taught artist. That phrase always seems like a bad word when you hear it in the art world. Have you run across any of that?

For me it’s a blessing. I see many of my fellow artists, especially those who are my age, they struggle to escape from these conventions. They always feel that need to reference something or someone. I don’t have that problem. Maybe because I am early in my practice, but I also don’t feel the need to be categorized. I don’t shy away from certain parts of photography that many people look down on. If you tell me I am a fashion photographer, I’m not offended. I see that as a compliment. I have a lot of respect for fashion photographers. Many of the art photographers who come from these schools feel it is considered something with no substance, while for me it’s the toughest part of creation because it needs to be fast, it needs to be good, it needs to be appealing. It tells a story. It documents the present time and gives a snapshot of what the future is. How can you not have respect for that?

Speaking of respect, the Diaspora project focuses not just colonization, but African greatness and the contributions black and African people have made throughout Europe, for centuries, most of which have been erased from what the West deems “history.”

Absolutely, absolutely, and it won’t stop with these projects. My mission is to establish the fact that as a black man, as an African, I come from a lineage of great people. We have great Africans and black men and women all around the world. The Lupitas (Nyong’o), Chimamandas (Ngozi Adichie). You name it. Actually, this started a long time ago. We’ve been pretty dope for a while. That’s what I’m trying to bring to the table. It is something that is ours. That recognition is something that we deserve. We have been deprived of that for decades, for centuries, and there are ways to fix it and my way to, at least, to contribute to this conversation, is to bring these interpretations that are fact-based. It’s not me making up things so that we have something to be proud of. It’s based on facts. These people lived. I put my touch on it, but basically it is just material that is designed to encourage people to go and do their homework and that’s exactly how it happens. When people come across my work they always will go and try to discover more. I just give snapshots. Even though it is based on history and facts, these should not be considered as historical documents. It is my interpretation but it can be a gateway to discoveries.

I look at the pieces Dom Nicolau and Jean-Baptiste Belley, which you presenting history, but using modern aspects, like footballs — soccer balls, to Americans. I find that rather intriguing, because one can still go to football games in Europe and they will throw bananas on the field …

Yeah, they do.

… at black and brown players even though the teams are mostly comprised of black and brown people.

That’s true. It was my way to somehow say, in a subliminal way, that what these African people went through. It’s still here. It just has changed. It has been tamed, it’s now shameful, but it’s still happening.

And on the rise again. It seems we are engaging in cultural wars …

Yeah. The nationalist.

Do you consider the foreign gaze when approaching your process?

I try to consider the universal gaze. Even though my topics are very African or African Diaspora–centered, I articulate it in a way that allows anyone to engage. I’m not doing art for black people. I’m doing art about black people that everyone can connect with, or at least have an interaction with. It’s the only way we can change that gaze, which still exists, and every now and then you get stupid questions, and you’re like, “Really?” For my show in London, there were several public engagements. I always expect the black and cool crowd, but actually it was so diverse. Every time. People of all ages and backgrounds. For me, that was a moment that I realized, “This whole diversity thing is actually happening.” Of course, the struggle is not over. But it’s happening. These people were not forced to come and they didn’t come because they were expecting to see some cool, exotic thing. They were knowledgeable. I was positively surprised.

Much like this moment where black artist are making strides, everyone also seems to be saying, “Africa is having a moment,” which we seem to hear every ten years, do you see that or does the thought belittle the strides being made on the continent? Or do you even think about it?

You know, I don’t think it’s a moment. It’s just that maybe there has been progress, which translates into people giving credit to those who deserve it, where it is due. Realizing that this black or African creativity has always been there, has always existed.

Which is why many Western museums have vast collections of African Art.

Exactly. We have not produced more art than before. There are not more African artists than before. No, I don’t think so. Now, they have to take it seriously and appreciate it. I don’t think it is a “trend.” It’s just that the art market has grown. It’s opening up. Maybe in a slower pace, but just like in the fashion industry, things are progressing. People have been fighting for this so it’s now happening. There is more diversity. Art and fashion, it’s just the same. I don’t think, on the creative side, anything is new.

How do you feel when people attempt to compare you to other African artist from the past?

That’s a complicated question and my answer changes every day. Through the years it has evolved. In the beginning I used to hate when people would compare me to Malick Sidibe or Seydou Keita. And you know what, I was right because I hadn’t incorporated their heritage into my work. What I was doing was really different. I was like, “This is B.S.” Because my first project, “Le Futur Du Beau,” it’s all on white background and there was nothing that was inspired by the great masters of African portraiture, but people were still telling me, “It’s so like Malick Sidibe.” It’s not. I’d take it as a compliment if it were true. It’s just you simplifying the whole situation. Then when I started my own portrait series (“The Studio of Vanities,” 2012), which was designed to continue their tradition, because I realized how great it was, this tradition of portraiture, and how it could be modernized and used as a way to continue this narration and see how people have evolved. I felt that one day, probably people are going to put a photograph of Sidibe, Keita, Mama Casset and mine, and people will see what has remained in the young, African, urban spirit and what has changed. So to me it was a contribution, then I was comfortable (with the comparison). That was the purpose. I think people get it. With projects like “Diaspora” and “Liberty” I don’t get the comparisons as much anymore. Of course, there is an influence, but it’s not the core of what I do.

You often appear in your work, but you don’t consider it self-portraiture.

No. Honestly, when I look at the pictures, which I am in, I don’t see myself. I see those characters. It’s something I’ve constructed, I know, and I guess it’s a way for me to detach myself from the artwork, to protect myself. You need that. But I don’t see these as self-portraits. It’s not me playing a role. It’s more me lending my body to a spirit. Because spirits live in a vacuum. Maybe it comes also from my African heritage. Even though now we’re all Muslims or Christians, we still have this belief that souls are somewhere in the air and every now and then you can invite them to enter.

So you are the vessel?

Yeah! That is exactly how I conceived these works. So for me, “self-portrait” is reductive. It’s a lot more than that. At least to me. When I was shooting each and every one of these portraits, I was all alone in the studio. I would be able to have anybody else because it really felt like I was meeting a spirit, a memory. Something that is here, that is latent. Something that just needs to be given a vessel for the time. So I could have a team around me. In general, I always work alone.

I suppose space and time is also about energy.

I agree. Creation is painful, it’s ugly, it’s full of doubt, it’s full of ego, and full of all the things that, to me, aren’t what makes art beautiful and useful.

Each time I come to Dakar, I see a great deal of social and commercial development. Do you feel the artist community has been growing with it?

Honestly, in the last couple of years I’ve been really withdrawn from the art scene here. Not by choice, just because I’ve been traveling so much. I’d have a problem making an assessment, because I haven’t really been involved. I’ve had some critics about that, but hey, I think my job, or the job I decided to take on, is of representation. I don’t need to represent us, among us. We know who we are. My battle is out there. That’s where this needs to be told because that’s where people don’t know it.