Within a few minutes of looking at one, a Peter Halley painting begins to move. First Halley’s squares, rendered in lurid cartoon tones of pearlescent puce and safety-cone orange start to pulse. The vertical and horizontal Day-Glo channels that stream from them like shimmering rivers of chintz seem to hum, the information rippling through them visible under their drugstore gift-bag surface. Before long, the whole thing is vibrating, a restless, insistent telegram from the future.

He’s been sending them for over forty years. Halley’s strict geometric vocabulary of prisons, cells, and conduits has remained mostly unchanged since he set it out in the ’80s, neat studies in discomfort that flattened minimalism, color-field painting, Constructivism, and Josef Albers’s squares into a sociological diagnostic of the isolating and anonymizing effect of technology on contemporary life. They emerged in the era’s moment of cool irony, both a postmodernist critique of geometric abstraction and an indictment of how we’ve arranged ourselves in the post-industrialist West, allowing instant connection to replace the messier human kind.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of Halley’s paintings, from this period and later, is how they feel of our current moment, with its unabating monsoons of noise and flashing alerts that wash over us, and the battalion of increasingly frictionless consumer products that connect us with ever more terrible efficiency. Halley has concurrent shows in New York this month. At Lever House, the 1952 monument of the International Style, Halley has installed new work, an immersive warren of rooms drenched in his nervous Day-Glo colors, as if the circuits of his paintings have broken free and metastasized. At night, the band of mezzanine windows, which he wrapped in electric acrid yellow film, buzz with a spooky, irradiated glow. Meanwhile, downtown, Sperone Westwater is exhibiting what it’s calling his “Unseen Paintings,” ten canvases completed between 1997 and 2002 that thrum with anxious energy and Y2K paranoia, made during a decade in which Halley’s work was rarely exhibited in New York City, his hometown, and when he was focussed on running then then quite influential Index magazine.

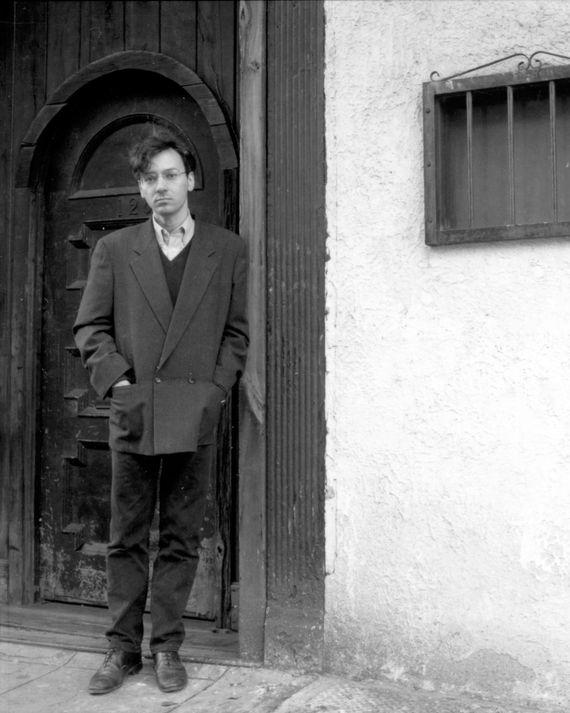

The Lever House show is a circuitous development for Halley, who was born a year after the building opened, on Park Avenue, and grew up two avenues over, and whose art turns on a kind of modern architecture-addled psychic dislocation. I met Halley at his Chelsea studio, where assistants were busy wrapping up new paintings bound for Europe. His portrait by Warhol, a version of which is included in the Whitney’s current Warhol retrospective, hangs above the toilet.

You grew up in an apartment on 48th Street and Third Avenue. What was that like?

When my parents moved there in 1956, it was still a residential neighborhood. My dad died soon after, and my mom never moved, so by the time the ’60s rolled around and all these skyscrapers were going up, I was growing up in this extremely strange, almost futuristic environment. It certainly had an effect on me. I’ve always been very uncomfortable, it’s just too much stimulation, and I never quite understood how my mom was comfortable there all those years — she lived there until she died. But doing the Lever House show, I’ve also become aware of how visually and spatially seductive it is. All those shifts of scale and contemporary materials, all that glass and metal next to some leftover brownstone. It is kind of kaleidoscopic, and intoxicating as well.

The canvases that you do, and have been doing, read to me as textures of the city, probably because that was my experience — my parents were living in a studio a few blocks away, at 54th Street, when I was born. But I wonder if that was the intent?

Well, I guess the answer is yes and no. I was newly back in New York and feeling quite psychologically isolated, and began to think of things coming in and out of these isolated spaces, like the telephone lines, electric lines, plumbing. I shortly thereafter added a second canvas, with the idea that these were underground conduits feeding these spaces. So it wasn’t just a cityscape, it was a diagram of contemporary life as it’s organized. I thought of these early works as cable TV, but it seemed to anticipate what was about to happen with the internet. I get a certain amount of feedback from people acknowledging that, not that I’m delusional to say that myself.

That was something that was remarkable to me about the Sperone paintings, because those were done around the late ’90s and early 2000s, and obviously there was the internet, but not to the extent that we understand it now.

Well, that was the era of the World Wide Web. So ten years later, all these connections have proliferated. In the Sperone work, by my own estimation, it becomes really baroque.

When you think of Malevich and Mondrian and Albers and their use of the square, that was an ideologically hopeful idea for a new society. I don’t get that feeling from your squares.

Yeah, I mean in that sense there’s almost a classic postmodern critique of geometric abstraction, and that’s how a lot of people see the work. So instead of seeing abstract geometry as utopian, I’m seeing it as dystopian. For Malevich and the modernists and Albers, the square was sort of the ultimately balanced form. I saw the square as something confining, and if you thought of it in terms of a modern environment, it could be seen as an isolating space. So the first thing I did was put bars on it and Roll-a-Tex, which turned it into this very childlike prison. That was the other great thing about Lever House: I physically got to do an installation in a space that is prototypically modernist.

Right, which seems like a real coup on Lever House’s whole idea.

It allowed me to install what I do within that context to get that dramatic juxtaposition.

Had you wanted to do something there for a while?

Well, you know, they invite people. There’s no application or anything. Let’s just say I was delighted. They only do two or three shows a year, so I wasn’t sitting by the phone.

But abstractly, you must have thought about what you would do in a space like that.

Back in the ’80s and ’90s when I used to write, I did address modernist architecture to some extent, but more so modernist geometric abstraction, so I’ve always been pretty direct that I was doing something in relation. Years ago, I read Rem Koolhaas’s book Delirious New York, which is so obsessed with Le Corbusier as this paradigm of modernist aspirations — so I quite identified with what he was doing there, kind of taking apart Le Corbusier and putting it together in a different way.

The Sperone paintings cover this period from 1997 to 2005, when you weren’t exhibiting in New York, but you were putting out the magazine Index here, with Bob Nickas, from this studio. What was the idea? There was a lot of Interview in it, no?

I felt Interview wasn’t so good anymore. It had become really commercialized. For me the mid-’90s in New York were kind of depressing. There was this huge crash in the art market. People were kind of gloomy. Bob and I were both looking to do something interesting. Actually, my first choice was to start a school program, sort of like the Whitney program, but I couldn’t find anybody to partner with, so Bob and I decided to start a magazine, and the idea was, basically, that we would do interviews, and also photography of people in their, let’s call it, natural setting. The first year, the covers were by Wolfgang Tillmans, who really as much as anyone else set the tone of the magazine. I personally identified the whole thing with New Journalism and Cinéma Vérité of the ‘60s, like, just tell it as it is. I do think subsequently magazines began to photograph portraits in studio settings less and pick up on this sort of snapshot style. We wanted people to tell their own story, rather than write about them. No offense.

None taken. You were publishing your own essays and art criticism, but had you had experience on the publishing side before?

Well, no. This was sort of a Warhol thing — I wanted to try being in business. And I was the publisher, never the editor, and the creative director, I guess. At the time, I sort of stopped writing, and I felt I had moved up a pay grade from writer to publisher. I pretty much took to it like a fish to water.

Did you prefer one to the other, publishing versus art-making?

Oh, well I could never give up art-making. But it was such a remarkable period because of all the different people we were in contact with. Being a journalist is sort of like having the keys to the kingdom, because often people want to talk to you. That’s how I met Brian Eno, and John Waters, and Wayne Koestenbaum, and lots of other people. But then in 2002, I got a job as director of the grad program at the Yale School of Art. That was really exciting. It’s hard to believe, until 2005 I did all three things. And then I closed Index.

Would you start it up again?

If the right person came along. Absolutely.

Even with the state of the journalism industry? What do you read now?

It’s such a challenge. I mean I’m pretty intrigued with the way art journalism has gone online. You know, it’s difficult. It’s challenging financially, but I think there’s more out there than there has ever been. There are a half dozen sites that publish interesting stuff, which is comparable to when art magazines were going full force in the ’70s. There’s a lot of art journalism reporting on fairs and that sort of thing, but there’s a fair amount of writing about art. I’ve read some really good things.

Do you think art fairs have become overly important?

Well, I always thought they were terrible, because the audience was basically a kind of global class of collectors who had the time and resources to go to these fairs, and of course the art doesn’t look very good. But then Instagram came along and all of a sudden instead of going to Miami, you could just flip through it, and I find that has been democratizing. I mean, I still basically think it’s an uncomfortable situation. This idea of deterritorialization, where art isn’t from some place but all gathered in this arbitrary configuration, and the diminution of the one-person-show and the dedicated space. It’s all pretty grim.

The Instagram art fair.

Well, I wouldn’t buy a work of art based on a photo, personally.

But people do.

They do and to be honest it would even be pretty hard to buy a work of art at an art fair — I mean maybe a Matisse — because everything looks kind of bad. In the digital era, one of the strengths of the visual arts is, basically, you do have to show up. You do have to go to the Lower East Side to go to a gallery, or go up to the Guggenheim, or whatever it is. I’m all in favor of any kind of positively motivated human interaction. People being with people.

So when was the last time you were physically present at a fair, because that experience is uniquely feral.

Yes, it is. I was in Miami a couple years ago. But I only spent about an hour at the fair.

So you didn’t go to the last Frieze here.

No, I didn’t make it. The first time I went, all I could obsess about was the building. I thought, This is so amazing. How much did it cost?

That’s the other idea: there is so much money in the art market.

I don’t want to be on a high horse about this, but with the massive popularization of contemporary art, I really think it’s gotten dumbed down, and a lot of people at the top end of the market aren’t really that interested in getting into it in depth. They depend on advisors and what experts tell them and so forth. And because they’re not that committed to looking at contemporary art in depth, they tend not to be interested in things that are complex or intellectually ambitious. When I was a college student in the early ‘70s, I got interested in contemporary art in relation to pop art, minimal art, conceptual art, postminimalism. It was really, really challenging intellectually, politically, socially. I wonder if I were 20 years old now if the art world would attract me in the same way.

Do you feel young artists feel pressured to make art that sells, as opposed to something they’re more interested in?

Well, I don’t know about that, I mean everybody feels the pressure to make a living. But I guess I’m saying the most popular art today is generally not that challenging. In place of that, I think we live in the age of the virtuoso. A lot of the artists most valued by the market really are tremendously virtuosic, and they do beautiful stuff, but it’s not always so thought-provoking. At the same time, the art world has gotten so big, there is kind of room for everyone — and so there are people doing other things that are more ambitious who aren’t as widely recognized.

Is it the appetite for contemporary art that’s growing, or the appetite for the commodity — is it any different from real estate, or bonds?

By and large those things have always been inseparable, going all the way back to the Renaissance. It’s just a question of what time and who was interested and what their values were. I think contemporary art was more expensive in the late 19th century. I’ve been reading something that indicates that. Artists like Meissonier and Rosa Bonheur — these salon painters who were hugely popular and did these immense paintings that sold for a great deal of money to a new class of capitalists. The market really isn’t my thing, except insofar as my interest in socioeconomics. You know that’s another thing — of course I want to make a living and have a nice studio and stuff like that, but for me, and I think for most the artists I know, the goal is not money, it’s recognition.

Of the ideas.

You ask an artist would you rather have a show in the Museum of Modern Art and drive a cab, or not have a show at the Museum of Modern Art and make a million dollars a year, nine times out of 10 I think you get MoMA. So all this money stuff I think is imposed on artists, it’s not really the artist’s thing. For the most part. I’m sure there are people who judge themselves on their prices.

To backtrack to your ideas and the development of your particular language, when you landed upon that, you kind of stuck with it. Is that because you hit upon something that you were satisfied with, or is it something you’re still trying to figure out?

Well, it sounds a little delusional, but I think this spatial arrangement of linear or controlled networks connecting these compartmentalized nodes is the space of our society. So for me, I’m painting what I see as the space we live in the way someone else paints landscapes. My work sticks pretty closely to a set of rules that are quite materialist: lines never overlap; there’s figure ground space but there’s no illusionistic space; when there’s a cell it’s not just a different color, it’s obviously a different texture. I guess those precepts mean a lot to me. But as one year goes into the next, the paintings continue to permutate and mutate and drift in ways I can never predict. And so, this closed system is also somewhat diaristic.

Even though the paintings have to do with this kind of discomfort and these oppressive, imposed systems, they’re very funny.

Humor is my favorite creative strategy, especially the Roll-a-Tex. When I came back to New York in 1980, one could easily identify the work of one significant painter from another by its characteristic texture or use of materials or brushstrokes or whatever it is. And in a kind of Warholian way, it seemed really funny to me to roll along my signature texture. There’s definitely a skepticism about the value ascribed to the artist’s touch.

How did you land on the Roll-a-Tex?

I walked into the local hardware store and there it was. It was a stroke of fortune because it’s a powder, so I could mix it with artist-quality acrylic and it wouldn’t fall apart. And Day-Glo paint was, I think, somewhat in the air in the early ’80s, Keith Haring used it, and Stephen Sprouse, but it appealed to me particularly because it was so anti-natural. It was like something you would never see looking out at the Grand Canyon. This idea of making paintings about a totalized technology-driven world where nature was excluded was important to me. In the early ’80s, this idea of nature as an absolute referent was something that was coming to and end, and that was really challenging for an older generation who were still very much invested in nature as the touchstone as what was real.

Do you think you’ll get tired of the model you developed, or rather do you think that the model will stop being relevant?

Clearly, in this infinitely interconnected nodal world, I’ve fallen behind a bit. But you know, this is typical of artists as they get older, a lot of one’s worldview is formed when you are younger. It’s sort of hard for me to start and look at 2018 as if I were 30.

You feel out of touch?

Well, I mean first of all things have become wireless, so I’m not sure you can talk about it in terms of lines as much as in terms of waves. The artist who I look to as representing the next generation is Andrew Kuo, whose work I really love and so directly addresses things like big data and constructing a social media persona. I think the paintings are just wonderful. I’ve said to him, I think of my painting as Web 1.0 and his as Web 2.0.

Did you consider yourself part of the ’80s New York scene?

Oh, yeah. I mean my first one-person show was at International with Monument in the East Village, which was a gallery that was supporting other artists that one would described as neo-conceptual and also pictures generations artists. Around ’84, ’85, ’86 was a very exciting time when I first met all these other people doing things that had some relationship to mine that I had no previous knowledge of. Somebody once described the pop artists in the early ’60s as being like that — none of them knew that the others were doing something along the same lines. And all of a sudden, they started showing here and there and discovered each other’s work.

Do you have a favorite cultural period in New York?

I tend to prefer the years in which we have a Democratic president. I should be clear because everybody thinks the ’80s was a party, but it wasn’t. The ’90s were grim in the art world because all these new artists stopped making a living and the art market shrunk and everyone thought contemporary art was bullshit. There was a real breakdown. But the ’80s were pretty difficult as well. First Reagan got elected president, and then there was a massive recession and by the time that was over, the AIDS crisis started. It wasn’t that great and a lot of the work from the ’80s was pretty dark, actually.

Why do you think you were more popular in Europe during that time?

Well, it’s still the case actually. First of all, Europeans are definitely more inclined toward conceptual painting. It’s just more popular. But the other thing is, and I’ve thought about this a lot — for a lot of Europeans, the 1920s and the Bauhaus and suprematism and all that stuff is considered a really significant cultural moment, almost like a second Renaissance. And I think that when a European audience sees something like this they say, well you know he’s addressing Malevich and Mondrian and this is what an artist has to say about that sort of thing now.

It’s just internalized.

It’s more a part of their cultural landscape. I mean none of that took place here so it makes a certain amount of sense. A lot of the Bauhaus people came here and had enormous influence, but there certainly isn’t a sense of cultural identification. Americans have always been skeptical of conceptualism, like it wasn’t artwork. It’s great to participate in the art world on both sides of the Atlantic and even little bit in Asia because there are all these shifting cultural factors that come into it. And I kind of feel fortunate to be able to get a firsthand look at it when I travel.

You have a show coming up in Stockholm.

Yes, my first time. They’re making me show in February. To cheer everybody up.