The 12th Shanghai Biennale opened on November 10 and runs through March, which — the current trade and tariff tussles with the current U.S. government aside — makes it a good time to visit the most ambitious of China’s many prosperous cities emerging into the world of contemporary art. The chief curator of the 2018 Biennale, held at the Power Station, China’s first state-run contemporary art museum, is Mexican-born Cuauhtémoc Medina. Medina is known for his keenly political curation of exhibitions like “Dominó Caníbal” (Cannibal Dominoes), 2010, at PAC Murcia, Spain, a yearlong series of shows in which each artist worked from what their predecessor left behind. Since its first edition in 1996, the biennial has argued for Shanghai’s place in international art discourse, and its rise in influence has paralleled that of the country as a whole. Solo exhibitions by the Biennale’s key figures commandeer some of the city’s major venues, like Francis Alÿs’s exhibition at Rockbund Museum, while commercial galleries like Arario and Edouard Malingue spotlight featured artists.

12th Shanghai Biennale

Power Station of Art

November 10, 2018 – March 10, 2019

A neologism borrowed from American experimentalist e.e. cummings’s sonnet “ViVa XXI,” the Biennale’s English title, “Proregress,” evokes competing conditions of stagnation and advancement. Inheriting a problem from its host city, the exhibition also navigated the mixed messages of Chinese cultural censorship and the similarly homogenizing neoliberal marketplace, leaving a slim ravine for, in the vein of cummings, the unpredictable and joyous. Thank goddess, then, for the deliriously overstimulating — like Lu Yang’s installation, featuring a playable Dance Dance Revolution-esque arcade game — and the coolly understated, Ilya Noé’s performance, for example, in which she walks backward in front of a scaffold-clad Berlin City Palace.

Francis Alÿs: La Dépense

Rockbund Museum

November 9, 2018 – February 24, 2019

In the post-conceptual era, carbon footprints skyrocketed: Artists started circuiting the world, not just their artworks. A formative work in Belgian-born, Mexico-based Francis Alÿs’s China debut is The Loop (1997) in which the artist circumnavigated the globe, in a southeast direction, to go from Tijuana to San Diego without crossing the Mexican-American border — like postcards, a series of small, pastel oil on wood paintings capture impressions snatched during the whirlwind world detour. The show culminates in his ecstatic, anti-productive Tornado (2000–10) in which the artist tries to run, with a jolting, handheld camera, into the eye of tornadoes, with even the recorded image sometimes flatlining due to proximity to the natural phenomena.

Nalini Malani: 1969–2018 Can You Hear Me?

Arario Gallery

November 6, 2018 – February 17, 2019

In Nalini Malani’s Arario Gallery solo, black-and-white photograms from the early 1970s depict theoretically rigorous experiments in abstraction, while a recent sequence of reverse-painted tondi, a type of circular painting or sculpture that became popular in the Italian Renaissance, interpolate cut-out texts (“You needed me. You needed to perfect me.”) into depictions of mythological femininity. A new series of digital video sketch animations, like her short Instagram videos, demonstrates Malani’s unending flair for restless images.

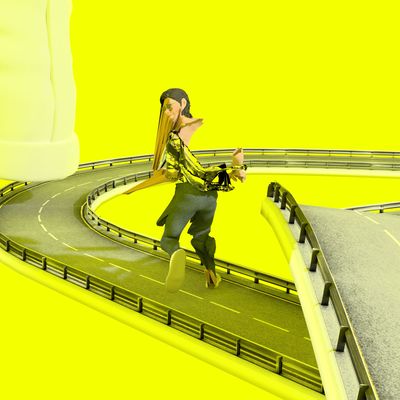

Samson Young: The Highway Is Like a Lion’s Mouth

Edouard Malingue Gallery

November 6, 2018 – December 23, 2018

In The Highway Is Like a Lion’s Mouth, Samson Young’s ever-playful practice whistles tunefully. The hind legs of a big, tan cat stick out of a blue wall; underpassing these, you reach a room with a purple carpet covered with candy-yellow lemon sculptures, the venue for the exhibition’s titular work: an animated music video that is also a road-safety educational jingle. Elsewhere, a bumper car, which amusingly appears as an oversize 3-D-printed shoe, edges across the gallery, emitting the jingle from the BBC’s classic radio show Music While You Work.

Wang Haiyang

Capsule Shanghai

November 3, 2018 – December 25, 2018

Wang Haiyang’s expressive, surreal videos are whirlpools in which images, stories, and styles collide — it’s not clear how deep they are, but one can easily be transfixed by their surface. The City of Dionysus (2018) recounts the artist’s childhood memory of hearing about a woman who lay dead in her apartment for days before her body was found, and is an existential meditation upon desire. The animation Skins (2018) shows an unidentifiable, sausagelike object floating in a field of rippling hairs, and is accompanied by intimate pastel portraits of hairy, lycanthropic, and gender-fluid figures.

Tschabalala Self: Bodega Run

Yaw Museum

September 22, 2018 – December 9, 2018

Tschabalala Self’s paintings iconographize the black female body, which she often drapes with packing materials and patterned fabrics. In Bodega Run, her portraits are accompanied by drawings of household commodities, standees depicting cats, a huge grape-soda neon, and sculptures of plastic crates, eliciting the environment of a bodega, a business praised by the artist for being “owned by people of color to serve communities of color.” Interspersed are framed and mounted color photographs that snapshot bodegas at night, with no people present, highlighting the complicated transactional purpose of these vital institutions.

Louise Bourgeois: The Eternal Thread

The Long Museum

November 3, 2018 – February 24, 2019

Under the looming concrete rafters of the Long Museum, Louise Bourgeois’s iconic, spinsterish Maman (1999) hatched an egg in my brain, and I realized, Why else do I look at art but to mourn my abandonment by my mother? Will I, in turn, abandon those who I love — including myself? I may have already done so.

You might react differently, since you have a different mother. Which is also why we look at art.