Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible. See his picks from last month and next month.

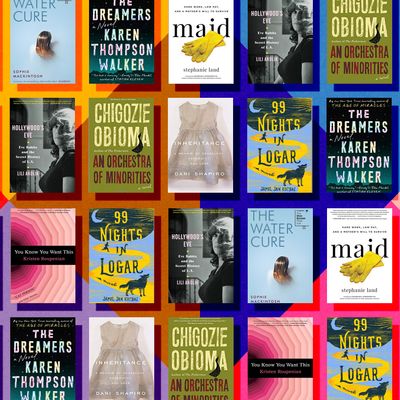

The Nigerian novelist’s debut, The Fisherman, was short-listed for the Man Booker Prize; this follow-up may do even better. A work of spiritual realism in the tradition of Ben Okri, Orchestra is narrated by the chi, or soul, of a lonely chicken farmer, which tells his tumultuous life story in accounting for his sins. (The farmer, Chinonso, saved a woman from suicide, then was conned by refugee traffickers and made some terrible mistakes.) Igbo and Greek mythology are braided into this heartbreaking and utterly unique novel.

The dark, cold aftermath of the holidays may be the best of times to read a biography of a groupie-muse who turned herself into one of Los Angeles’s most evocative nonfiction writers. Reversing the title of Babitz’s rediscovered collection, Eve’s Hollywood, Anolik turns the lens on the writer, showing how Babitz gained access to everyone and everything in louche ’60s and ’70s L.A. and recorded the experience for posterity. Anolik makes no apologies for adoring Babitz — for being only the latest in a long line of admirers held in her thrall.

What could have been just a loose collection of stories coheres into a warm but appropriately rough-edged picaresque about war-torn Afghanistan. Marwand returns from the U.S. to his native country at age 12 and almost immediately has the tip of his finger bitten off by a dog. When the offender flees, Marwand and other rascals set off to exact revenge, meeting family members along the way who fill in the dark gaps of Afghani history. Kochai balances whimsy and dread, innocence and experience, and Marwand becomes a modern-day Huck Finn.

Dystopia with a feminist cast has blossomed in the last few years, for not-too-mysterious reasons. Mackintosh’s entry is among the best, not least because it gets to the root of the genre by dissecting a warped utopia. Three girls are kept on an island by Mother and King, protected from a world in which toxins have made all males dangerous — or so they are told. Eventually, three men arrive on the island, and twists ensue — not cheap pyrotechnics but reversals of moral structure, revelations that demonstrate why the subtlest fiction is often the most powerful.

Walker’s first novel, The Age of Miracles, was also a near-future dystopia. Her second fits into a subset of that genre that you might call epidemic fiction. In a small California college town, a freshman girl fails to wake her roommate; soon many townspeople are comatose, yet dreaming frantically, as the result of a virus. There are quarantines, escape attempts, families torn asunder, instances of life carrying on — all the usual stations of the fictional outbreak, but handled with uncommon delicacy and realistic detail on every level. And that’s before we get inside the dreams.

This collection, which emerged from the feeding frenzy following the viral success of Roupenian’s New Yorker story “Cat Person,” meets its own high expectations. Some stories, like “The Good Guy,” delve just as brilliantly as “Cat Person” into the perversities of the male psyche, while others attack thorny questions about what women privately want. Some excursions into fantasy feel new — and organic to the material. Together, these fun and furious stories put the lie to the complaint that millennial politics are humorless or rigid.

For a novelist and author of four memoirs, this fifth memoir feels like a culmination — the result of a shocking discovery Shapiro didn’t realize she’d spent her life preparing for. Decades after the death of both her parents, she learned that her father, the scion of generations of rabbis, wasn’t her biological parent. The revelation, via a casually taken ancestry test, comes early in the book, and Shapiro spends the rest of this spare, lyrical story shattering the polished portrait of her life and piecing the fragments carefully, gorgeously back together.

Some memoirs about rising out of poverty focus mainly on structural inequality (Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland), while others privilege dramatic personal stories (Tara Westover’s Educated). Land lets us have it both ways — beginning the journey in a homeless shelter as a poor single mother, traveling through the wealthier but still unhappy homes she cleans for a living, and winding up in Montana as a budding writer. In a country whose frayed safety net gets less policy attention than the marginal tax rate, Land is the anomaly only in surviving to tell the tale — and in telling it with such compelling economy.