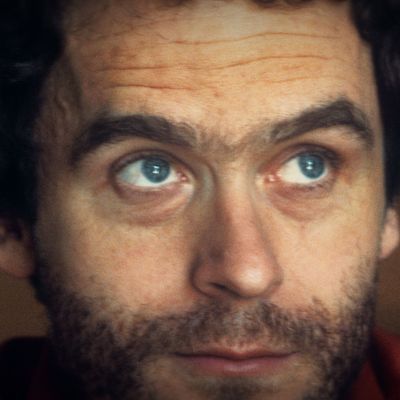

Ted Bundy, who was executed 30 years ago after confessing to the murders of 30 women, loved attention but didn’t want to be caught and punished for his crimes — a common conundrum among serial killers. Bundy was one of the most prolific, and, if the new Netflix documentary series Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes is to be believed, one of the slipperiest, hiding in plain sight as the bodies piled up.

Introverted, physically awkward as a child, and insecure about his family’s relative poverty in a Seattle neighborhood full of well-off neighbors, Bundy aged into a young man who created an aw-shucks persona that helped him insinuate himself with the random young women that he’d ultimately murder and sometimes rape as well, before or after their deaths. Other times, he simply invaded their homes and attacked them while they slept; one of his first documented victims, Karen Sparks, survived a beating in her own bed with a metal rod that Bundy then used to violate her. His spree made international headlines. Throughout the long police investigation — which included Oregon, Idaho, Utah, and Colorado, where Bundy had branched out to avoid detection — the public was mesmerized by the savagery of his rampage. In retrospect, the accumulated details of the case made Bundy seem supernaturally terrifying, a wraith in the shape of a man. At Lake Sammamish State Park, where two women disappeared on the same day in July 1974, witnesses told police they spotted a would-be pickup artist fitting Bundy’s description, but they couldn’t match him to photos of Bundy. Investigators later learned that in the spring of 1974 — a couple of years after working as a local organizer for the Seattle Republican Party on Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign — Bundy somehow ended up assigned to a crime commission that was studying, in one former police officer’s words, “the chaos and lack of consistency from one [police] jurisdiction to another,” and might’ve been inspired by that experience to start his murder spree, armed with inside knowledge of how to exploit weaknesses in the system.

If you’re interested in true crime, and serial killers in particular, you might already know all this. Joe Berlinger’s four-part Netflix documentary won’t add much to your body of knowledge, as brilliantly structured and edited as it is, and it’s what’s elided or ignored that ultimately distinguishes it: the personalities and stories of Bundy’s victims. Dating back to the 1960s and ’70s, when the first modern serial killers seemed to start popping up all over the United States like a disease outbreak that had assumed human form, psychologists and editorialists have cautioned against letting a fascination with serial killers shade over into a twisted version of hero worship — the sort of adolescent thirst that leads to the cross-comparison of killing stats and relative intelligence, as if murderers were athletes chasing after the same trophy. Conversations With a Killer stays on the right side of the ledger, but just barely. It treats Bundy as a horrifying void of a man whose true emotional interior remains just out of sight, a Kurtz hidden in moral and psychological gloom no matter how much light is cast by detectives, reporters, and childhood friends.

Near the end of the first episode, we get a eureka moment from reporter Stephen Michaud, whose 1980 audio interviews with Bundy — recorded on cassette while he was on death row — form the spine of the documentary. Michaud tells Berlinger that he realized a traditional jailhouse interview wasn’t getting him anywhere, because Bundy was weaving a false narrative about himself that tactically avoided describing his then-alleged crimes. Then he got the bright idea of asking Bundy to talk about himself in the third person — sort of a Hannibal Lecter–style killer-as-consultant scenario, undertaken a year before Thomas Harris published his first novel about the famous fictional killer. Being an insatiable self-dramatist, Bundy took the bait, analyzing himself in exhaustive detail, but always with plausible deniability because he was speaking not about himself, but of a hypothetical other person. But as ingenious as this gambit was, and as fascinating as Bundy’s analysis is, it doesn’t get us any closer to the core of what made him tick. In fairness, perhaps nothing could — not even a narrative device that gives a convicted killer permission to analyze himself as if he were a character in a literary nonfiction bestseller like In Cold Blood or The Executioner’s Song. “This is the defect of history that historians have to deal with,” Bundy tells Michaud on tape. “I guess we’re all historians. I mean, talk about fiction — that’s what history is.”

Even with a full and self-deprecating acknowledgment that Bundy still lies when he claims he’s telling the truth, and despite the editors’ superb interweaving of personal photos, police evidence, and archival footage of ’70s Seattle, Conversations with a Killer seems largely unaware of its own obliviousness. Just because the series, like Michaud, can’t get to the center of Bundy doesn’t mean that the only potentially interesting storytelling avenue has been obstructed, and therefore there’s nothing a filmmaker can do but say, “People are ultimately unknowable, and Bundy is no exception” — which is where the story seems to land, approximately four hours and countless virtuoso displays of filmmaking craft later. There were at least 30 other stories that Berlinger could’ve told: those of Bundy’s victims. More, even, had the documentary chosen to expand the stories of his childhood friends, or the detectives and patrol officers who were traumatized by their investigation of his crimes. With a few fleeting exceptions, the people whose lives Bundy damaged or stole remain abstractions, one step up from numbers on a ledger.

This is particularly disappointing in light of Berlinger’s track record. He might be the most acclaimed and influential specialist in the true-crime documentary, excelled only by filmmaker-philosopher Errol Morris, who’s playing in a slightly bigger sandbox because his crime movies are more likely to focus on accused war criminals (like Robert S. McNamara and Donald Rumsfeld) than the kinds of men who kill people face-to-face and dispose of their remains. Berlinger and his late filmmaking partner Bruce Sinofsky arrived on the scene 27 years ago with Brother’s Keeper, about a poor, illiterate upstate New York man accused of killing his own brother, and went on to co-direct the Paradise Lost trilogy, about child murders in West Memphis, Arkansas. One of Berlinger’s distinguishing artistic features is his mix of chilly, almost Kubrickian detachment and genuine empathy for the misery of individuals whose communities are shattered by homicide. The first quality is present in spades here, but the second has largely gone missing. That Conversations With a Killer is apparently a prelude to a fictionalized, black-comedy version of the Bundy story, starring Zac Efron as a matinee-idol handsome version of the killer, is nearly as disturbing as the documentary series’ recounting of nearly 50-year-old crimes. Bundy may have been a black hole of a human being, but he was surrounded by a constellation of other stories that are worth telling, too.

*A version of this article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!