ThereÔÇÖs a long legacy of artists having bands. Mike Kelley, David Wojnarowicz, Yoko Ono, Richard Prince and Jean Michel Basquiat all had them. The artist Genesis P-Orridge started Throbbing Gristle┬ábecause of what an old man at a pub told her. He was someone sheÔÇÖd regularly chat with and ÔÇ£heÔÇÖd been gassed at the Somme in World War One and he had about two teeth,ÔÇØ she says. At the time, the Dada-influenced collective P-Orridge co-founded COUM Transmissions, which was getting a fair bit of press for their controversial performances, including live enemas and 10-inch nails. ÔÇ£I understand why you are doing these strange things, Gen, but what about the other people in this pub, would they understand?ÔÇØ the old man asked her. He suggested music as a way to reach a maximum amount of people with the same ideas, and this inspired P-Orridge to start her industrial band Throbbing Gristle in 1975.

Artists start bands for lots of reasons. The creative impulse to make music often comes from the same place as what inspires artists to make the other art they make, whatever that might be, paintings, sculptures, video installations. But the context music exists in ÔÇö the clubs where itÔÇÖs playedÔÇöis far less pretentious, and more fun. Plus it gets artists out of the studio and up on stage. (And, as an aside perhaps, who gets laid more than musicians?)

Starting a band was in another era a fuck you to the lofty art world. In ArtForum in 1983, Kim Gordon wrote about the art school kids who started No Wave bands in the late 70s, of which she continued the lineage with Sonic Youth. ÔÇ£Their involvement in music, spurred on by the cynical, anarchistic aspects of punk rock, was an alternative to alignment with the art world.ÔÇØ

When P-Orridge looked to start making music, it was in part motivated by this feeling that ÔÇ£the art world was getting too precious, too careerist, and somewhat sterile.ÔÇØ While she felt that the art world favored being formulaic ÔÇö ÔÇ£you had to repeat yourself over and over to succeedÔÇØ ÔÇö ┬áP-Orridge saw more potential to really challenge people to think about human behavior and our cultural programming through making music, precisely because she was untrained as a musician. ÔÇ£One person wrote even an ape with severed arms could play the bass guitar better than Genesis and I thought brilliant, we are certainly breaking down the musical traditions.ÔÇØ

This idea of deconstructing whatÔÇÖs been done in the past to make something new motivates artist-led music projects both then and now. With his band the Black Monks of Mississippi, sculptor and social practice artist Theaster Gates says heÔÇÖs ÔÇ£kind of an interloper in the field of musicÔÇØ trying to find ÔÇ£what else is possible?ÔÇØ But these projects no longer exist outside the art world the way they once did. Even though it was formed as an alternative to it, Gordon notes that ironically the art world embraced the No Wave movement. These days anti-diva Kembra Pfahler, who fronts the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, is a darling of museums and blue chip galleries with work like butt prints and reproductions of posters promoting her band the playing at CGBGs.

Today we have a pretty expanded definition of art. If urban redevelopment or a mobile hair salon can be an art project then of course a band can be too, but also thereÔÇÖs a utility to welcoming these energized performances into hallowed institutional art spaces. Art bands and multi-hyphenate artist-DJs are mainstays of museum galas and youth-oriented programming, gallery openings after parties, and luxury brand-sponsored art events. For instance, GatesÔÇÖs band played the Prada VIP club last month during Art Basel Miami Beach.

Today Gen X artists like Wolfgang Tillmans and Kai Althoff also have their musical side projects while millennials like Juliana Huxtable and James Ferraro work in both music and visual art as well as poetry, itÔÇÖd be hard to say which one most prominently ÔÇö in our post-internet age, itÔÇÖs maybe easier to work across multiple mediums as most content ends up distributed online in some capacity anyways. But still, many artist-led music projects seem to follow in the lineage of those from an earlier era, conceiving of their performances more visually than a typical rock band ÔÇö with think costumes, props, and video projections. Their approach can be more conceptual too, whether about meta-narrative or representation. And sometimes artists having a band can also be a fun collaborative project thatÔÇÖs a foil to an isolating studio practice.

I talked to members of six artist-led music projects ÔÇö including the band that P-Orridge currently fronts, Psychic TV ÔÇö about how they got started, how they navigate between art and music contexts, and their biggest influences.

IUD

IUDÔÇÖs roots go back to Lizzi Bougatsos and Sadie Laska meeting in art school when they were 18. After they graduated, they moved together to New York in ÔÇÿ97, sharing an apartment. ÔÇ£We were trying to be artists but we were poor and didnÔÇÖt have studios. A way to be creative was to make music with your friends,ÔÇØ says Laska. They started the art rock band Actress with artist Amy Gartrell and painter-DJ Spencer Sweeney, whoÔÇÖs today a sometimes member of IUD.

Laska ended up moving to DC and Bougatsos got deeper into the music world, starting the world-music-infused electro pop band Gang Gang Dance in 2001. (In the early aughts, Bougatsos also had the metal band AngelBlood with artist Rita Ackermann.) When Bougatsos was touring in Japan with Gang Gang, she discovered this all-girl band with two drummers OOIOO, the side project of the BoredomsÔÇÖ Yoshimi P-We. ÔÇ£I was absolutely blown away by them,ÔÇØ says Bougatsos, and it got her thinking who could I drum with? She heard Laska had been drumming in a band in DC and was moving back to New York. In 2004, they started IUD.

ÔÇ£When we started drumming together, Sadie and I had different styles but when we locked in that was key. ThereÔÇÖd be these moments when we were totally synchronized and people were like you look like youÔÇÖre about to have sex,ÔÇØ says Bougatsos. ÔÇ£Those moments are pretty primal and organic and for me thatÔÇÖs what drumming is all about.ÔÇØ

Bougatsos notes that some art bands are almost like ÔÇ£puppet theater,ÔÇØ but for her ÔÇ£instrumentation and musicality take precedent.ÔÇØ Still, with IUD, thereÔÇÖs more room for getting weird than with some of her other projects. ÔÇ£Gang Gang is very much traditionally a soundscape ÔÇö we are crafting sound almost like an orchestra ÔÇö and IUD is a soundscape too, a very loud soundscape, but also with IUD we never know where the performance could go,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£One time in Zurich with IUD, I lost my voice and I put on this mask and just crawled around the space. Spencer Sweeney continued playing the drum kit and Sadie just followed me filming.ÔÇØ

Laska whoÔÇÖs primarily a painter, appreciates that the band is a welcome escape from working alone in the studio. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve always liked collaborating, and Lizzi and I are great collaborators,ÔÇØ she says, ÔÇ£It comes from when we were in art school and we did weird performance pieces together.ÔÇØ Bougatsos adds, ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre both capricorns. WeÔÇÖre both the same age. We grew up together. We just get it.ÔÇØ

JD Samson

After studying experimental film at Sarah Lawrence, JD Samson first became the video projectionist for Le Tigre and then later joined the band led by riot grrrl pioneer Kathleen Hanna (and in which artist Sadie Benning also played for a stint). ÔÇ£My input into that project was visual first. I actually never studied music,ÔÇØ says Samson, who today teaches at NYU TischÔÇÖs Clive Davis Institute for Recorded Music. ÔÇ£One of my classes is about where performance art and conceptual art meets music performance.ÔÇØ

Le Tigre, which Samson eventually joined as a proper band member, very much straddled the art and rock worlds. ÔÇ£We incorporated performance art, costume, choreography, and video, and I guess you could say all of that was conceptual art including the project in and of itself, which was really focused on the visibility of our feminist activist selves. Being on stage was almost the art project,ÔÇØ explains Samson adding, ÔÇ£Our music was sample based. We werenÔÇÖt necessarily trained musicians in the sense we werenÔÇÖt even working in a specific key.ÔÇØ

After Le Tigre went on hiatus in 2005, Samson and Johanna Fateman formed the band MEN, continuing to mix feminist politics with dance music and performance art-y sets. Bougatsos ┬áremembers, ÔÇ£JD would wear this TV box on top of her head. It reminded me of the Residents, that band with the eyeball heads.ÔÇØ On their 2013 sophomore album Labor, MEN had a song expressing support for Pussy Riot.

ÔÇ£After MEN took a break, I had been performing as JD Samson but I felt like IÔÇÖd been relegated to the music world,ÔÇØ says Samson adding, ÔÇ£I was feeling a bit uncomfortable about that.ÔÇØ At a visual art residency, she started experimenting with rock sculptures and then incorporating them into performances. Last year at the Lower East Girls Club, she collaborated with other artists, performing with a shirt made of strung-together rocks, and at Ballroom Marfa, drilling into rocks. ÔÇ£I was using the drill and the rock as an instrument,ÔÇØ explains Samson.

These days, Samson also has the cheekily titled project New Band with No Name with musician Roddy Bottum (Faith No More, Imperial Teen). They played at the Kitchen accompanying a Laura Parnes film commenting on the Trump era. ÔÇ£Our song was called ÔÇÿPretty Shitty,ÔÇÖ talking about how weÔÇÖre all feeling pretty shitty┬áapathy in our community,ÔÇØ says Samson. SheÔÇÖs hoping that the new band can incorporate some of her experiments with rocks as instruments in the future, too.

Hairbone

The origin story of Hairbone begins about a decade ago when their guitarist Nathan Whipple saw artist and frontman Ra├║l de Nieves performing at a Chelsea art gallery, where he was part of a group show. ÔÇ£Ra├║l was just amazing,ÔÇØ says Whipple, so he wrote him a letter suggesting that maybe they could collaborate. Together they started a band Try Cry Try and roped in their friend Jessie Stead to help out with video projections. Eventually the three of them became Hairbone ÔÇö formerly Haribo, named after the German gummy company. ÔÇ£At first it wasnÔÇÖt as musical with songs and stuff. It was kind of more just like a freak out, type of thing,ÔÇØ explains Stead. ÔÇ£We started to write songs more and made a set list that the freak outs would weave in and out of.ÔÇØ

The three-pieceÔÇÖs performances are full of wacky theatrics, wigs, and homemade props, like cardboard washing machines. The typical set up is Whipple on guitar, Stead on an electronic drum kit, and de Nieves on the mic foregrounding the performances with his hypnotic restless energy. In the past, theyÔÇÖve described their music as ÔÇ£sexy clown, post butt-metal party anthems.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£We can play in a museum and the next time a bar or a basement,ÔÇØ says Stead. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs such a DIY thing. ItÔÇÖs been fascinating to have a museum present that. In a way, itÔÇÖs sort of out of context in a museum but itÔÇÖs also not. ThereÔÇÖs a long history of art punk bands that we fall in line with.ÔÇØ

The band fits into the artistsÔÇÖ respective practices in different ways. de Nieves is interested in transformative experiences. ÔÇ£This live act opens up so many portals in the brain. The band has provided a platform for all three of us to release a sense of energy and anxiety,ÔÇØ he says adding that ÔÇ£the energy of the audience is just as important as the music.ÔÇØ Stead, in turn, explains that documenting the band is part of her video practice. ÔÇ£I think about the band as a story. Its life ÔÇö its beginning, middle, and end ÔÇö to me, itÔÇÖs like a decade-long movie.ÔÇØ

de Nieves is influenced by bands like Bikini Kill and Le Tigre as well as avant-garde musicians like Philip Glass and John Cage. Stead links what HairboneÔÇÖs doing to other art bands like Mike KelleyÔÇÖs Destroy All Monsters. And Whipple is inspired by the music that artist and friend Ryan Trecartin makes on FruityLoops for his absurd videos (in which the band members sometimes feature). See for yourself how these influences all come together in a raucous Hairbone performance when they play next Tuesday, February 5th at Trans Pecos in Brooklyn.

Mhysa

ÔÇ£Mhysa grew out of my studio work,ÔÇØ says Philly-based multimedia artist E. Jane about their alter-ego persona and music project. Jane started making lip sync videos in grad school, including them in early iterations of their ongoing Lavendra installation, which explores the legacy of the black diva through sci-fi mythology. ÔÇ£I love pop stars and singing these songs but I was doing it through this character because sheÔÇÖs more femme than me and more performative than me,ÔÇØ explains Jane, who uses the genderqueer pronoun they while their persona Mhysa uses she.

A professor in grad school suggested that Jane take the lip-sync performances more seriously. ÔÇ£I want sincerity from you,ÔÇØ he urged. Jane thought, ÔÇ£The realest thing would be if I were to make an album.ÔÇØ They submitted an EP as a midterm in grad school and MhysaÔÇÖs first full length album fantasii came out in 2017. ÔÇ£I do the graphic design, the production, sometimes the video editing,ÔÇØ says Jane. ÔÇ£I think a lot about it as total art or gesamtkunstwerk.ÔÇØ Other influences include ORLANÔÇÖs body performance, Lynn Hershman LeesonÔÇÖs fictional Roberta Breitmore character, and riot grrrl rap persona Mykki Blanco.

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm really adamant about Mhysa not performing in a gallery because sheÔÇÖs not that type of an art piece. It would be too self referential like the snake eating its own tale. She performs out in the world,ÔÇØ says Jane, adding that club parties like GHE20G0TH1K are the ideal space. ÔÇ£Performance ephemera can go in the gallery, performance documentation can go in the gallery, but the live performance, I want that to go on a stage.ÔÇØ

Mhysa has toured prolifically this year across Europe and North America. The live act features DJ support by JaneÔÇÖs partner and collaborator who makes makes music as lawd knows and art under his given name chukwumaa. Together the two artists also have the experimental club music project SCRAAATCH. Thinking about working between different contexts ÔÇö in addition to nightclubs, SCRAAATCH has played PS1ÔÇÖs Warm Up series, the Chelsea art-performance venue the Kitchen, and they have a monthly show on the online radio station NTS ÔÇö chukwumaa notes that in the music scene, theyÔÇÖre a part of ÔÇ£thereÔÇÖs a lot of interlopers who are art-oriented or literally have art degrees making music with functional club sounds but they have an entire artistic premise to it as a first thought, not as a second thought.ÔÇØ He adds, ÔÇ£the press releases might as well be artist statements.ÔÇØ

MSHR

Brenna Murphy and Birch CooperÔÇÖs project MSHR (pronounced mesher) grew out of the Oregon Painting Society, a five-person art collective formed in Portland in 2007 which defined both its method and goal as ÔÇ£transcendent creative collaboration.ÔÇØ Cooper says the collective wasnÔÇÖt medium specific but ÔÇ£engaged in a wandering aesthetic approach.ÔÇØ This kind of radical collaboration can take a lot of patience. ÔÇ£It took us a long time before we got anything good,ÔÇØ recalls Murphy.

OPS eventually developed a practice of creating interactive audiovisual environments, which MSHR has continued to build on since 2011. ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre an offshoot from the original, like a space pod from the main ship,ÔÇØ says Murphy. MSHRÔÇÖs mad scientist performances feature trippy multi-sensory feedback loops made possible by light-activated synthesizers and sound-activated lights.

Cooper says heÔÇÖs always been interested in the potential of collaboration as a way to achieve ÔÇ£something you couldnÔÇÖt have thought of on your ownÔÇØ ÔÇö he specifies that he values exploring both collaboration with other humans as well as collaboration with software. While MSHRÔÇÖs work often takes the shape of set at a music venue, albeit one with more strobing lights than your average noise musicians, they also design interactive sculptural installations like Sonic Arcade at the Museum of Art and Design in 2017, which featured a generative system integrating the sounds of museum-goers. Both Murphy and Cooper also have solo art practices.

ÔÇ£We operate in a lot of different contexts,ÔÇØ says Cooper. ÔÇ£Those contexts determine who we are in that moment.ÔÇØ Murphy adds that with MSHR, they are conscious of how these different contexts influence audience expectations. ÔÇ£Sometimes we are very aware that people are coming in more on the visual side or more on the sound side,ÔÇØ she says.

Cooper and Murphy are very influenced by other art collectives, including La Monte Young and the Theatre of Eternal Music, later known as the Dream Syndicate. ÔÇ£They made these long-standing sound and sculpture installations,ÔÇØ says Murphy. (You can visit of the Dream House, an immersive installation created in 1993 by Young and Marian Zazeela in Tribeca.)

Psychic TV

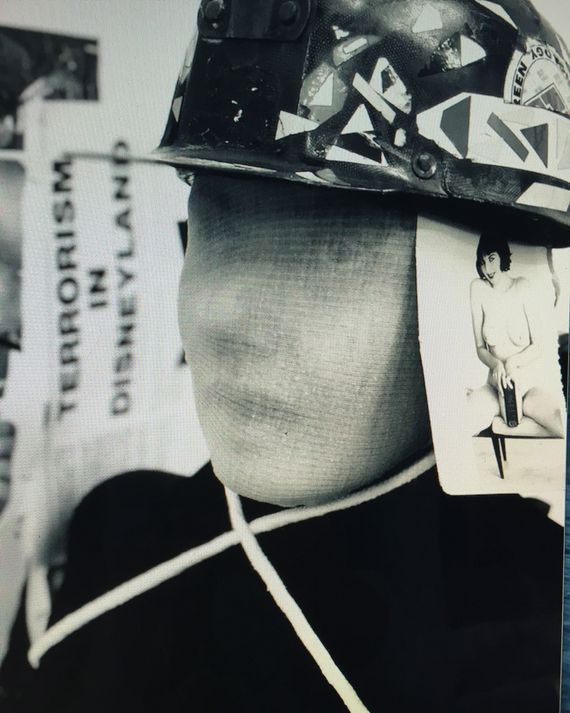

ÔÇ£A band doesnÔÇÖt just have to be four or five people on a stage doing the same tired rock ÔÇÖnÔÇÖ roll moves,ÔÇØ says P-Orridge. ÔÇ£My first band, Throbbing Gristle, we did things like one time we had mirrors all across the stage so the audience could only see themselves. Another time we played in a cube of scaffolding with TV cameras all inside, so you could watch us on TV monitors all around outside but if you wanted to hear us you had to go to the roof because the PA was pointing to the sky. You could only watch or listen, you couldnÔÇÖt do both at the same time.ÔÇØ

P-Orridge continues to bring this same spirit of innovation with the group Psychic TV, which she formed in 1981 with Alex Fergusson and another ex-Throbbing Gristle member Peter Christopherson. Over the years, Psychic TV experimented with industrial music, acid house, and psychedelic pop, and many different musicians, artists, and writers have been involved in the project including Fred Giannelli, Larry Thrasher, Derek Jarman, and LSD evangelist Timothy Leary.

Psychic TV has always centered video. In 1982, they released the First Transmission in a series of four VHS tapes, which montaged together scenes of rituals, home drug videos, grotesque surgery and scarification, and archival footage of Jim Jones. Today their performances feature a psychedelic light show of video projections. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a very spiritual experience,ÔÇØ says P-Orridge.

Over the years, throughout these musical experiments, P-Orridge says, ÔÇ£I always carried on making art.ÔÇØ Whatever the medium, P-Orridge approaches everything like a cut-up. ÔÇ£I see the world that way, constant fragments of fascination swirling around me,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£Everything is collaging for me. ItÔÇÖs one of the only ways to guarantee new combinations. No sort of linear thought would give you that. IÔÇÖve applied that idea to everything music, art, photography, my own body, and itÔÇÖs always given me amazing results.ÔÇØ

This cut-up approach features in a Psychic TV remix for Trent Reznor that reworks the track with audio of howler monkeys waking up that an LA zoo, or P-OrridgeÔÇÖs sculptures that mash up shoes of her sex worker friends with animal horns and voodoo ritual items, which are on view right now at Marlborough Contemporary. But also in the Pandrogyne project, where P-Orridge and her late partner Lady Jayne underwent body modification to physically resemble one another and unite as one entity.

ÔÇ£A lot of LGBTQ people have heard about the Pandrogyne project and come out to see Psychic TV,ÔÇØ says P-Orridge, whoÔÇÖs 68 and currently battling leukemia. ÔÇ£The reason why IÔÇÖm prepared to do the band even when IÔÇÖm sick is that weÔÇÖre getting more and more people than weÔÇÖve ever had and they are getting younger and younger and more and more enthusiastic. WeÔÇÖre getting a lot of people from the LGBTQ community and thereÔÇÖs not been a lot of gay rock. TheyÔÇÖre coming to a completely new celebration of loud music and lights and videos. So many people say that itÔÇÖs inspired them and I feel a real responsibility in that. ThereÔÇÖs a sense of unity and deep trust that makes it so worthwhile.ÔÇØ