“I’m not a responsible person, you know — at all,” says Richard Prince, as if he is trying to remind himself of this as much as anything. “I’m just — I want to make cool shit. I want to be a cool dude, or whatever.”

Today, at 66, Prince is one of the most successful and influential artists of his generation — specifically, the Pictures Generation, an aloof clique of 1980s conceptualists that included Barbara Kruger, David Salle, Jenny Holzer, and Cindy Sherman (whom he used to date), who together reintroduced pictorial imagery to painting, in large part by borrowing it directly from advertising and mass culture. In music they call this “sampling,” and for Prince it started with his reshooting magazine ads with the logos of the products cropped out (he was working at Time Inc. and became fascinated by Marlboro cowboys). This new art was considered, at the time, a kind of critique of the aspirations advertising saddles us with. Some of the images, which Prince describes as “too good to be true,” were cropped or repeated, others simply held up, by Prince, for closer inspection. And the inspection could be lusty, especially when the images were icons of swaggering Americana. Recently, trying to explain the process, he wrote on his website: “It’s like sometimes I feel I’m fucking what I’m looking at.” His most memorable work is still a photograph he took of a photo of a 10-year-old Brooke Shields, standing naked in a tub, shrouded in steam, her hair and face made up, her body oiled like some ancient-days courtesan, which a photographer named Gary Gross had taken at Shields’s mother’s own behest.

rince called his version Spiritual America, a name that was also an appropriation — the title belonged to Alfred Stieglitz’s close-up of the genitals of a castrated male horse —and showed it in a gaudy frame in a small, semi-anonymous gallery he opened in a storefront on then-ragged Rivington Street in 1983, called Spiritual America too. At the time, some people compared it to a peep show, but what he had really done was create a semi-furtive place where prurient interest would be given an avant-garde alibi. The gallery kept irregular hours to keep out outsiders, which might not have been simple showmanship. In 2009, well after Prince had become famous, the work was removed from an exhibition at the Tate Modern by the police, who explained they wanted the museum to “not inadvertently break the law or cause any offense to their visitors.” Today, Spiritual America belongs to the Whitney, but you can’t look at it on its website — it’s hiddenbehind a large gray X.

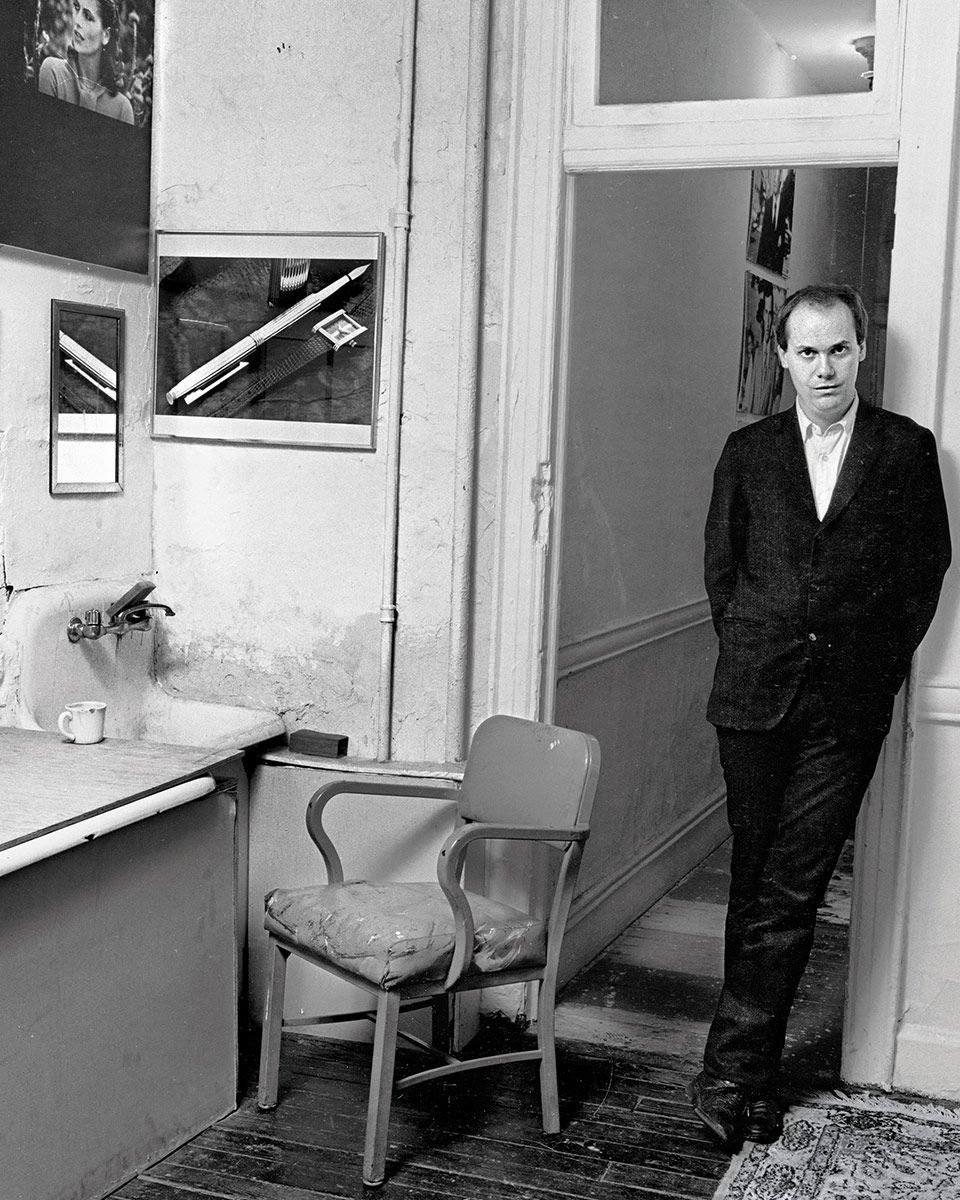

In 1983, Prince priced the work at $100 and failed to sell any of the edition of ten. There was an art boom in the 1980s — perhaps you remember Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat? — that also lifted the careers of a number of Prince’s friends (e.g., Sherman, Kruger, Salle, Jeff Koons). But it largely bypassed Prince, who circulated among the hot young things of the era, a punk bad boy with a repaired cleft lip and OCD tendencies who talked about how his parents were spies. He didn’t make any real money on art until his 40s: Collectors didn’t feel in on the joke, even after the Whitney did a Prince exhibition in 1992 (a Marlboro cowboy gallops across the catalogue cover).

Then two things happened: In 1994, Prince — 45 years old, divorced, with a cocaine-and-the-Odeon habit — abandoned his Reade Street loft and retreated upstate. “I was a mess, I was cracking up,” he says. In Rensselaerville, in an unheated garage, he put together a loose series of paintings intended as a sort of farewell that were very literally mocking. “On the very first one, which I still own, I painted a little cocktail martini glass and I wrote donations. I looked at it and said, ‘I like this, but I know no one else will. This will get me out.’ ” The advertising tycoon and megacollector Charles Saatchi saw them in the basement of Barbara Gladstone’s gallery and bought six of them. “It was classic,” Prince says. “I had been making work at that point for almost 20 years. Just when I thought I was out, they pulled me back in.”

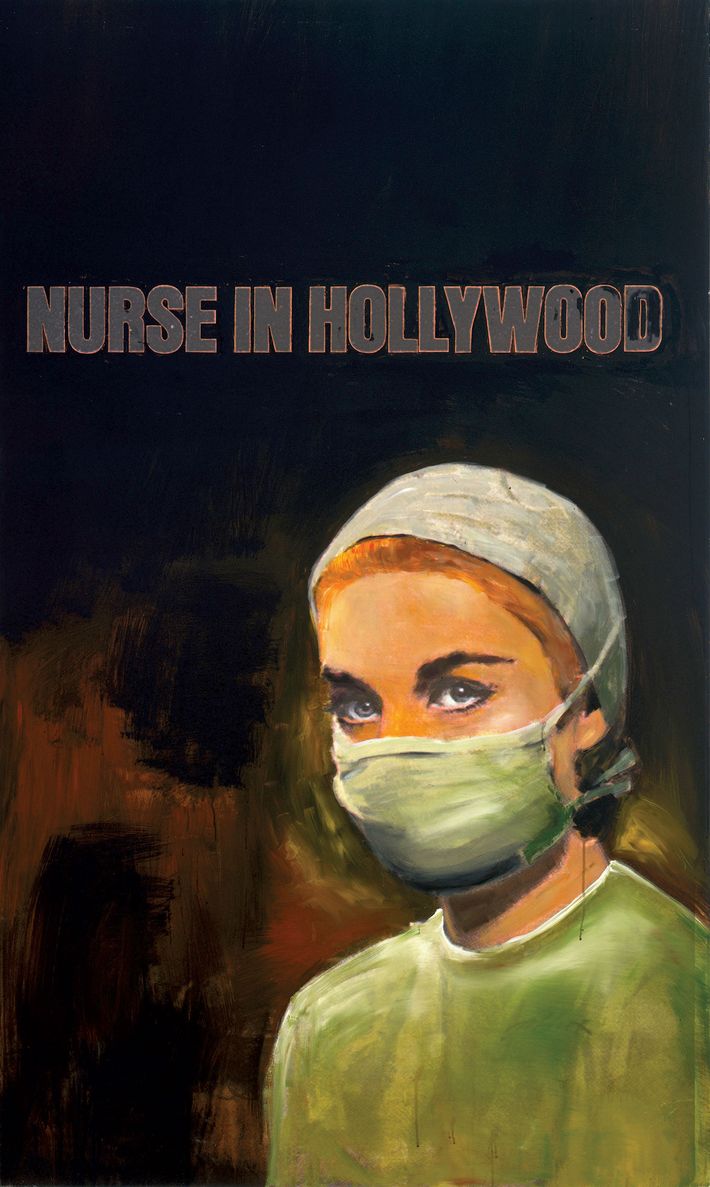

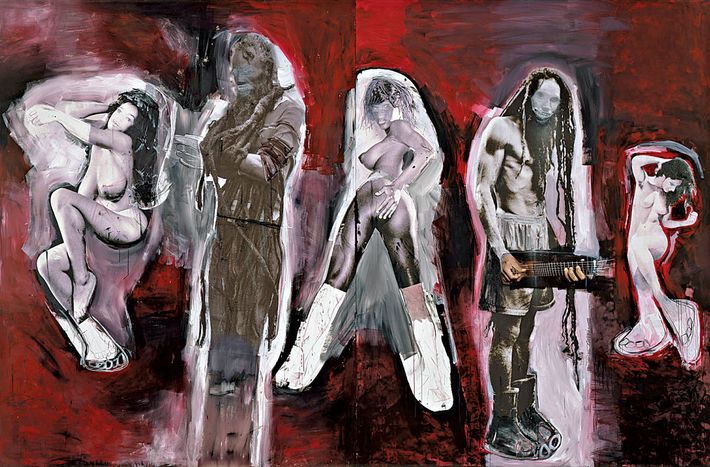

A decade later, the collector Peter Brant saw something in a new series of blurry, sexy canvases Prince called “Nurse” paintings, inspired by pulp book covers. “Spiritual America made him great, but the ‘Nurses’ made him rich,” says one art-market big shot who watched it happen. Brant told friends in the art business that Prince could be a “new Andy Warhol,” with “a fractured but large and interrelated body of work he could assemble quietly into a vast treasure trove.” The result, collector Jean Pigozzi tells me, was: “All these hedge-fund guys are always going, ‘I have six Richard Princes!’ ” In 2005, one of his Marlboro-cowboy rephotographs sold at Christie’s for $1.2 million, more than any photograph before it. “Richard was never interested in the market — ironic that the market caught up with him,” says Nancy Spector, who curated his he’s-finally-arrived Guggenheim retrospective in 2007, when the artist was 58. As an auction-house executive puts it, “Even people who misunderstood Prince completely would buy Prince.”

This misunderstanding was likely intentional, and certainly gratifying to Prince, who has a curious relationship to his own success, given that he is very wedded to the idea that success is bullshit. “Richard, I think, he does like to play the bad boy, the outlaw,” says Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, also a friend (in 2004, she put a “Nurse” painting on one of their album covers). “He’s very deliberately courted the image of the outsider,” agrees Spector.

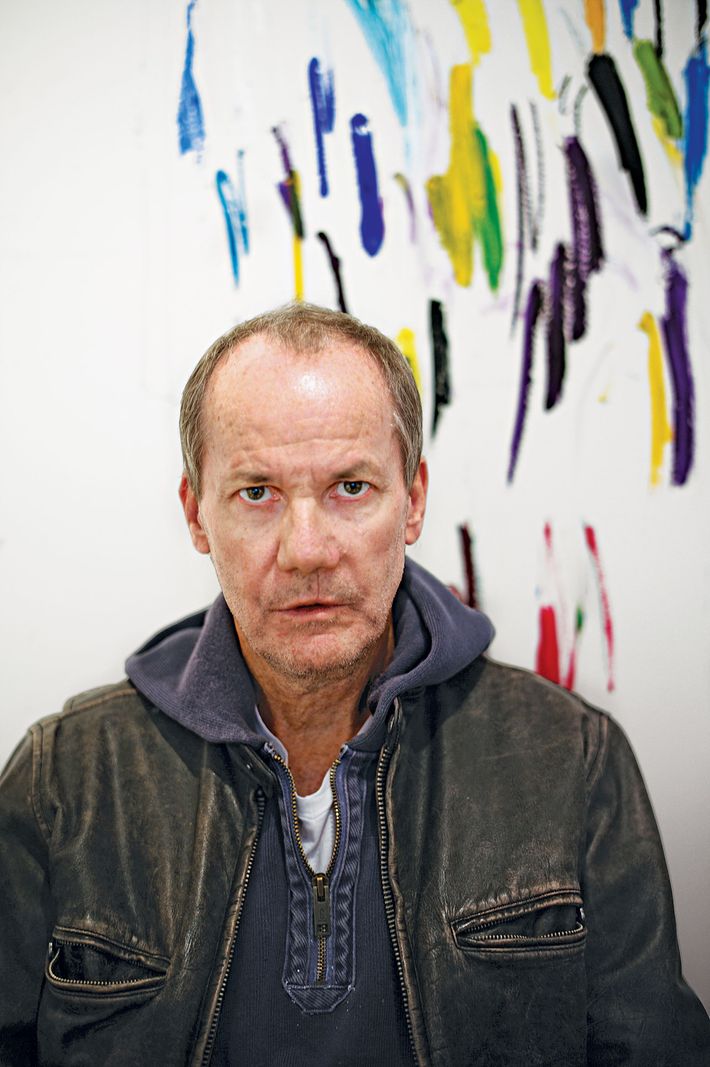

And these days, he does look the part of the aging noise-rock musician. A slight, pale man, he wears a daytime uniform of paint-splattered jeans, white T-shirt, and Doc Martens when I meet him in the almost generically upscale duplex apartment he rents and uses as a studio and office in the East 70s between Park and Madison. It’s next door to the townhouse where he and his family live, which he bought in 2009, post-“Nurse” mania, for $11.5 million. He also owns a second townhouse, one building down, for which he paid $13.75 million in 2012. And there’s a place in the Hamptons and that place upstate in Rensselaerville, now metastasized by his success into what’s been reported to be a nearly 300-acre spread, with a miniature museum for his extensive art collection and an archive for his rare-books collection — friends joke that he owns the “entire town.”

But talking to Prince, you don’t exactly get the sense that he’s settled into, or even come to terms with, his immensely comfortable life. He still says quaint things about doing battle with the “squares.” And the compulsive squall of his rancorous id is certainly obvious if you follow his Twitter or Instagram accounts. Recently he’s been trying to engage with Kanye West via Twitter: “Now people think we’re having some feud,” Prince says. “I don’t think he even saw it. And then someone said, ‘Kanye gets 7,000 retweets and you only get two.’ And I said, ‘Yes, but the two I get are from Larry Clark and Christopher Wool.’ ”

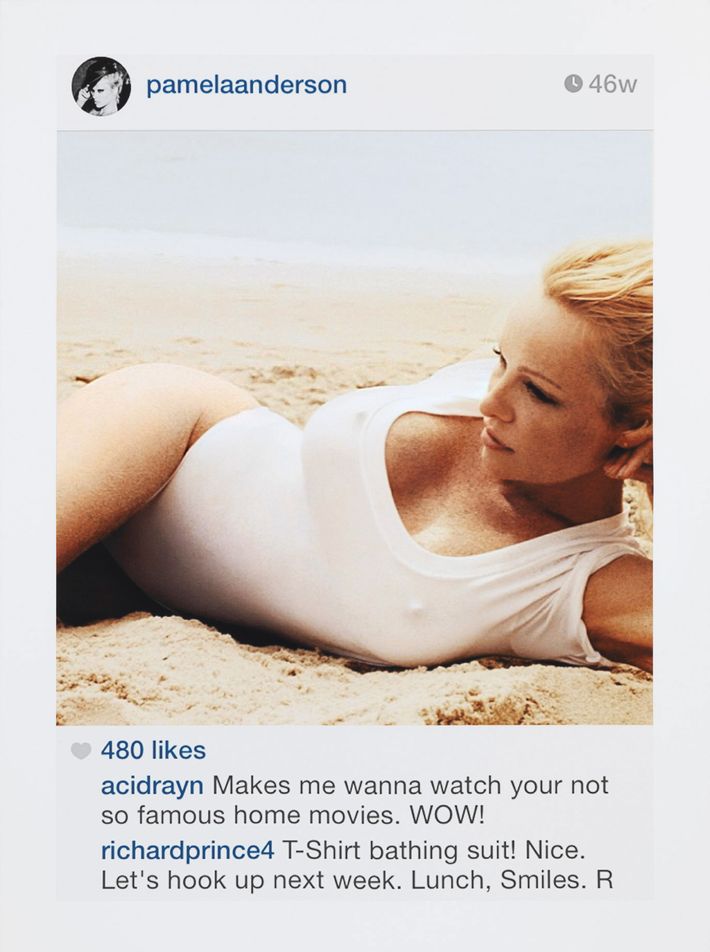

Which brings us to the recent runaway affront of Prince’s Instagram “portraits” series, four-by-six canvases printed with blown-up screen grabs of — more often than not — fetching young women engaged in social-media sexual self-branding. The paintings, each of which also features a comment from Prince communicating with the person, were reportedly sold by Gagosian for $90,000 a pop and prompted another round of cultural hand-wringing about the ethics of appropriation. Prince has always been blunt about stealing — the outlaw idea is the core of who he is as an artist. And he’s endured reputationconfirming copyright-infringement lawsuits over the years; like a good punk, he did it by eye-rolling his way through depositions. But the appropriation played a little differently when the man doing it was a very rich artist in his advanced middle age commenting on — or critiquing, or possibly just being a creep about — all these young women. In The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl wrote that “possible cogent responses to the show include naughty delight and sincere abhorrence. My own was something like a wish to be dead.”

Prince’s experience of the squabble was a bit different. “What was really strange was that I had a hit, meaning people wanted them right away,” he says. “Which was a very strange experience. Because usually when I show work — well, for the first 30 years, nobody bought a copy of the cowboy.” He chalks that up, basically, to ignorance. “I swear to God, I still have people come up to me and say: ‘Hey, man, when’d you go out West?’ ”

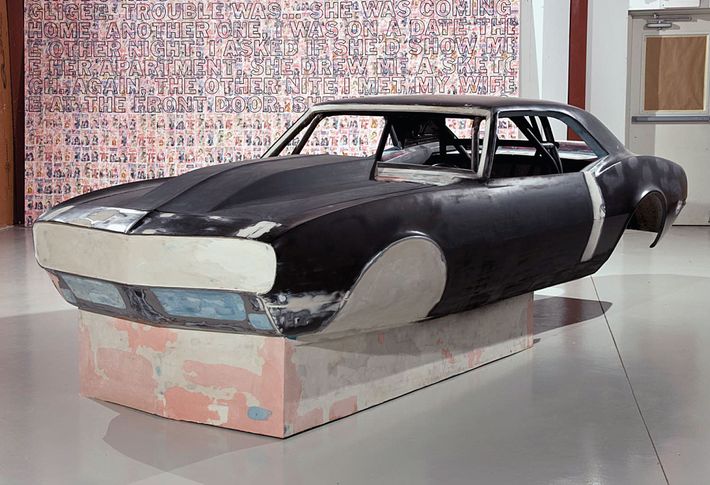

Two years ago, Prince leased a formerly industrial building in Harlem that counts among its neighbors, he points out, as if listing its bona fides, a methadone clinic and a post office where he says “Son of Sam” David Berkowitz worked. He calls the building (four stories, with a side yard) a studio, but uses it more like a showroom and personal gallery. “Basically it’s a place to look at work when it’s been made,” he says. Which means it is also therefore something like a declaration of independence from the gallery system — specifically, Larry Gagosian, with whom he’s worked since 2007 but whom he’s often spurned (showing both at his old gallery Barbara Gladstone and 303 Gallery, run by his ex-wife, Lisa Spellman).

“It’s an old system that he operates in,” Prince says dismissively of Gagosian. “He’s still working in the system Daumier operated in. That system is radically changing now because of social media or whatever.” It was hard to miss the irony when Prince’s assistant chased me down to insist that I delete from my phone the pictures I had taken of the space when I walked in — they apparently didn’t want anything that wasn’t ready to be seen on social media to turn up there. But it’s not exactly a new irony for Prince, who’s also done things like use copyright protection to prevent museums from publishing in a catalogue images of his early work, which he doesn’t like to be seen, even when the museum is staging an exhibition of that work (which he no longer owns and therefore can’t control). You might think the lesson of Prince’s early appropriation was that all of visual culture was up for grabs, but a few decades later, the clearer through-line to his work is that he wants you to see things exactly as he does.

This month, a new series of Prince’s work was shown at Sadie Coles in London; they’re paintings based on old Playboy cartoons depicting lecherous men and busty women, but painted over with riotous primitivism. Still, the Instagram paintings seem to preoccupy him, and when he meets me at the Harlem studio, it’s on the floor hung with them (other floors house other bodies of work). So he sets about explaining how he makes them.

He loves his iPhone, he says. He tags posts that appeal to him and contributes to the “comments” in a weird kind of self-invented patter. (Guy goes to doctor naked wrapped in Saran Wrap. Doctors says, “I can clearly see your nuts”; Cray flea in dle tray so trust me if bull fly up Chee sez. Sez Me!) He calls this his “bird talk”: “These short wacko stupid sentences. Soupy Sales Groucho Marx Rod Serling Finnegans Wake.” Then he Photoshops out the comments appearing above his own and emails the new version to his assistant. And then they ink-jet them on specially chosen canvases.

“I had to be convinced when I brought them in,” he says of the first time he showed the works to the staff at Gagosian, in 2014. (Larry himself didn’t see them until they were hung.) “I said to the people who work there: ‘I don’t know about this. Do you really think this work is any good?’ ”

We are seated in a couple of sleek chairs, a coffee table between us. It could be a sales office for a new condo, but instead we’re surrounded by these paintings of mostly young people. “The truth is, I don’t care who they are; I care who I think they are,” he says, looking around. “I’m not a very social person. I don’t go out at night. So maybe I wish I looked like them or I could be them.”

He continues, “I’ve never understood popularity, but I need to understand what is popular. My wife is always getting on me for watching Entertainment Tonight, but I’m like: ‘I need to know what’s going on.’ Even though I don’t understand. Like I don’t understand the Grammy Awards or Taylor Swift. It’s not for us.” He and his wife, the artist Noel Grunwaldt, do try to keep up, he says, with help from their kids, one a DJ who lives in Bushwick and the other a student who introduced him to Instagram.

“There’s such narcissism out there. This Caroline Vreeland girl over there? She apparently is a minor celebrity, and hangs out with all these 30-year-old rich kids. And she was desperate for me to do a portrait of her. I heard this through Derek Blasberg” — he pronounces the Vanity Faircontributor’s name Blasenberg — “Derek calls me up and says Caroline is desperate for you. And I said, ‘Really? Let me look at her feed.’ That’s how this works: how fucked up it is, or how it can get fucked up …” (Reached for comment, Blasberg Googles Vreeland, says he has no clue who she is, has never met her, and certainly never told Prince about her; that did happen, though, with the model Karlie Kloss.) “The other thing about Instagram is that it’s so fucking democratic,” Prince says. “And I am aware of that. It satisfies these things in me — my desire to be everything, whether it’s like gender, race, dress up, dress down. I have to say in the end it’s fun. And a lot of the art I’ve made isn’t that much fun. It’s a struggle.”

The portraits were also inspired by Warhol. “I finally read Bob Colacello’s” — he pronounces the name Coachella — “book about Andy Warhol. It was basically about his portrait business. And that’s how he made a living. I was very aware of it when he was alive. It was 25 grand a pop. Warhol was a worker bee, bringing home the bacon. There never could be enough money because he was afraid. And that is something I can understand. Someone could come in here and take it away from you. Whether it’s the government or a lawsuit. And, listen, I’m in fucking plenty of lawsuits. And always have been. I sometimes spend more time in my lawyer’s office than in my studio.”

This is the downside of fighting for your right to not be responsible (he’s being sued again, now by the photographer Donald Graham). “I’m not going to change, I’m not going to ask for permission, I’m not going to do it. I don’t know how to do it that way. I don’t respond that way. It doesn’t occur to me that anybody is looking still … In the end, the artists I hang around with — Christopher Wool, Bob Gober — I don’t think they think about audience. I don’t think they necessarily think about money. Why would anybody do that? Some younger artists do. But unfortunately art comes out of a personal crisis you’re having.” Later, he adds, “I don’t want to go back to a tub in the kitchen. Although sometimes it seems like it would be a hell of a lot simpler.”

Prince is known for making things up, especially about himself, in his writing and in interviews, possibly to make himself or the world seem more interesting, mysterious, or full of dark possibility — he calls it “wild history.” (As it happens, he is friends with A Million Little Pieces author James Frey, whom he met after his public shaming: “I always kidded him, ‘You should have met me before you went on Oprah.’ I could have schooled him: ‘Fuck you, I don’t give a fuck what you think, this is what I wrote, whether it’s true or not, who gives a fuck.’ ”)

But the story goes like this: Prince was born in the Panama Canal Zone, where his parents worked for the government. He grew up in Braintree, Massachusetts, an obsessive young man who liked to rearrange the furniture in his room. He never went to art school, a fact that seems important to him to this day (“practicing without a license,” he calls it). And his idea of New York was a place where you could dress like Bernardo in West Side Story (“the suit he wore to the gymnasium dance”).

He was living in Boston when he read a story in The New York Times Magazine about a restaurant in Soho called Food, which was run by artists — it seemed like a thing he wouldn’t mind checking out. So in 1974, he moved and eventually landed a back-office gig in the library at Time Inc., and an apartment in what’s sometimes been called “the poets’ building,” 437 East 12th Street, home to Allen Ginsberg, Luc Sante, and Rene Ricard. Prince paid $77 a month, and removed the stove to have more room to work and think. He played in noise-rock bands and wrote a book called Why I Go to the Movies Alone (first line: “A lot of people wish they were someone else”), all while going to work pretending he was Sidney Falco from Sweet Smell of Success. Time Inc. “was like living in a giant dystopian novel,” he remembers. “I made up in my head that when I entered the building I didn’t have to come out, everything was provided for me.”

In 1977, he got the idea that he ought to “rephotograph” the tear sheets of the advertisements in the magazines, without the text. “The people who ‘got’ appropriation were a bit like the people who liked the Velvet Underground,” says Spellman. The Pictures Generation was “a much cooler aesthetic,” she says, and “nobody had been analyzing publicly consumed images like Richard and Cindy.” It was a radical insight, perhaps all the more impressive given that, years on, living in a click-and-drag, information-wants-to-be-free world as we do now, it has come to seem almost banal. “At first it was pretty reckless,” Prince said in a conversation with his friend Barbara Kruger published in BOMB magazine in 1982. “Rephotographing someone else’s photograph, making a new picture effortlessly … I always thought it had a lot to do with having a chip on your shoulder.”

“He had a slow start,” acknowledges Gagosian. “He is not an overnight success. His market struggled; his career struggled. I think that people didn’t know what to make of his work.” But that had an upside: “He got used to trying different things. If they don’t like this, what about this?” A longtime acquaintance of Prince’s told me that “he can treat the world like it’s a TV and he has the remote control.” Another way of putting it is that he feels entitled: He wants to get inside everything, and feels it is his right to claim it.

“I think it’s interesting to think back at the time when he was dating Cindy Sherman and she was this megastar young artist and he was kind of the artist’s boyfriend,” says the dealer Bill Powers, a friend of Prince’s. “He told me about how once they went to a collector’s house who owned both of them,” and he was excited that at last they were on more even footing. They arrived, and her piece was front and center. “He didn’t see his work,” Powers says — it was hanging in the bathroom.

His friend Brendan Dugan, who runs the art-book shop and gallery Karma, passes on another (possibly apocryphal) story from the era (he says one of the best things about being friends with Prince is his stories from the ’80s): “I guess Jeff Koons had told Richard to come over to his new apartment. And everyone was living in the East Village in shitty apartments. But his was on Fifth Avenue. And Richard was wondering: How the hell did Jeff — who is basically a total fuck-up at that point — get this place? The elevator opens into this apartment and it’s a pretty fancy place. There’s a brand-new washing machine in the center of the apartment — and nothing else. Jeff is explaining how this is his new sculpture. It’s called The New, it’s never been plugged in. And Richard says: ‘How can you afford this place?’ And Jeff says: ‘I paid the first and last month’s rent and it’ll take them a year to kick me out.’ ”

“You had the sense that they all were obsessed with money,” remembers a friend who used to hang out with Prince and Warholite Glenn O’Brien in the Hamptons. “They saw through the art market — that it’s such a scam.” But trying to topple something is just another, more punkishly stylish way of claiming ownership over it. Dugan tells me about the time, in the late ’70s, that Prince and a few other artist friends (Robin Winters, Jenny Holzer, Coleen Fitzgibbon, Peter Fend, and Peter Nadin) started an “aesthetic consultancy” that lasted for a few years. It was sort of a gag, but they even had an office on lower Broadway. A lot has always been made of Koons’s brief gig, in that era, as a commodities trader, especially given the uncomplicated reverence in his work for perfect consumer objects. To critics, Koons is often seen as a kind of bête noire of Prince’s, but in a way the appropriation work is just as acquisitive, animated by a similar consumer libido, for all the artist’s punkish bravado. As one curator puts it, “Jeff can be hokey, and Prince is sinister.”

“I didn’t have a real studio until 1989, when I could afford it,” Prince says. “I’ve never really thought about an audience, and still to this day I don’t really think in terms of having a huuuugeaudience. I think it’s very tiny. I know the art world is getting bigger and more global, but for me art is always still done by the few for the few. It’s not that I’m elitist, but it’s not the most democratic thing in the world.”

Gagosian describes Prince as a “wily, tenacious guy. But he’s also kind of lovable. He can be difficult and withdrawn and cranky and moody, but he’s got a good heart.” More important, Prince is immensely devoted to the idea of himself as a troublemaker and shit-stirrer. “He’s a gunslinger,” Gagosian says. “He’s kept his edge. Artists get soft, but he hasn’t. He can’t function any other way.”

“I’ve had lunch with Richard 20 or 25 times, and it’s always in some dingy diner somewhere,” Brant says. “He has his own vision. It’s not like you can advise him or steer him. Whenever I look at his work, I take the position I think this now, but in five years I might think something different.” More often than not, Prince’s work has proved prescient.

Prince denies he has many friends, and will often avoid even his own openings (though he loves to dance and has a dance party every time the Frieze art fair is in town). And these days, he mostly hangs out here on the Upper East Side. “I don’t really leave this block that much,” he says, though he wishes his favorite nearby old-school coffee shop hadn’t closed.

Stuck to the wall of his studio behind him are: an old magazine advertisement for a 1970 Dodge Challenger (“My muse,” he says); a check he never cashed from the Whitney Museum (he collects checks of famous people, and he has a body of work called “check paintings,” which use grids of checks as a painting surface); and a 2014 obituary torn out of the Times: “Otto Petersen, the Voice of Vulgarity, Dies at 53.” One of Prince’s heroes. “Nobody knows about him. He is a ventriloquist. And the puppet is really fucked-up looking. He just couldn’t work, he was so vulgar. There’s a video of him doing the Adult Video Network awards in Vegas, and there are shots of the audience with their mouths open — what did he say? And these are porn stars.”

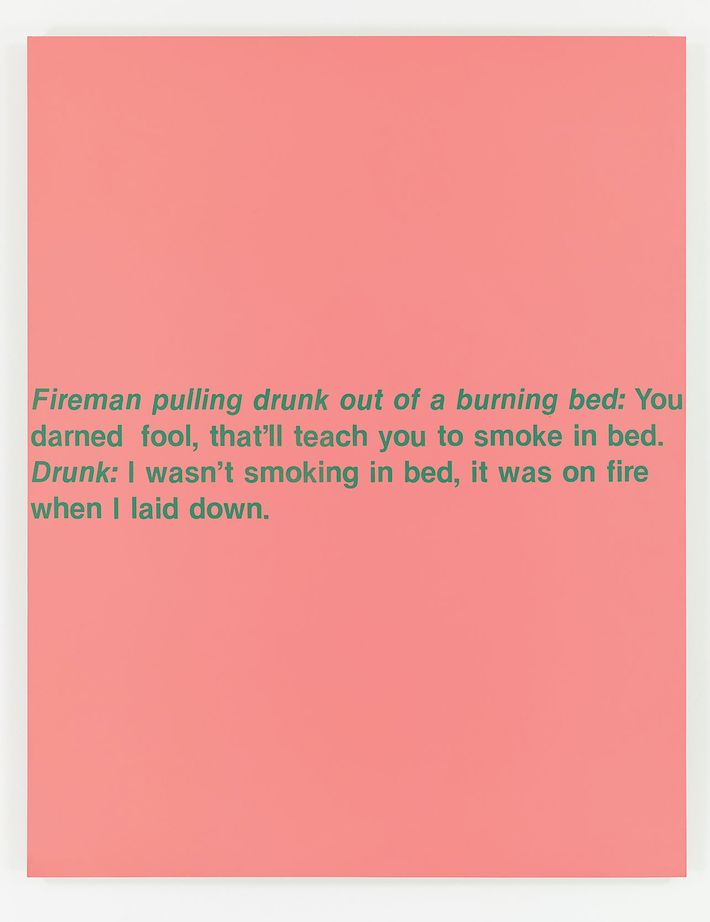

For years, Prince has appropriated self-deprecating Borscht Belt one-liners for his “Jokes” paintings, and he really loves comics, he says: He names Don Rickles, Sam Kinison, Richard Pryor. “There is something so special about comedians,” he says. “They don’t have any responsibility. They also get a pass. I have an easy pass and they have an easy pass. And maybe certain musicians: the Cramps, Bad Brains, Iggy Pop. They don’t give a flying shit.”

“It’s hard to be subversive, but it’s harder to stay subversive,” says Glenn O’Brien. “I think some people think he’s being campy or a wiseass. But actually Richard captures America better than anyone.”

Not everyone is so sympathetic. “The only thing which makes him a bad boy anymore is the court cases,” says one auction executive. And those lawsuits did seem weirdly consequential, as though the meaning and legacy of an entire art movement were going to be decided by people all the artists involved would probably consider philistines — and who would, in turn, see some delusion in megarich artists’ claiming to be outsider pirates. At this point, Prince and his cohort have more or less won the cultural argument over copyright — this is the way we all live now, blithe with our endless hoard of imagery. But that victory has a perverse way of making the appropriation artist seem a little less ahead of the curve. Prince spent six years fighting for his right to use (and profit from) others’ images, particularly the dozens of photographs of Jamaican Rastafarians by Patrick Cariou that formed the basis of his 2008 show “Canal Zone,” which generated more than $10 million in sales at Gagosian. An appeals court found that the images in 25 of the 30 works had been sufficiently transformed by Prince to deserve protection; ultimately, he reached a settlement with Cariou over the other five. “You can’t discount the fun of making trouble,” says his friend the director Harmony Korine. “The consequences of trouble almost don’t matter. The trouble is what is exciting. The trickery is the really fun part. For Richard the lawsuits are also the artwork. They were a joke. He’s devoted to that idea.” And even today, as the secure winner, Prince seems really unhappy to have had to play by the rules of the court — or really any rules.

“I hated that lawyer; that lawyer was really an asshole,” he says about the plaintiff’s counsel. “I just wanted to be like — my attitude was like, Dude, this is my artwork, and you are a square. You are a fucking square. For me, it’s like I wasn’t going to be a part of his world, I wasn’t going to acknowledge his world. And I knew that I would win in the end. I know Oscar Wilde; I know Lenny Bruce. You don’t argue aesthetics in front of a judge. And if you don’t know that, you’re pretty stupid. The judge doesn’t know shit about aesthetics; he knows the law. I don’t know anything about the law. Copyright? That’s absurd. The only thing I know a little bit about is art,” he says. “Maybe I was playing that card, or was overplaying it. I don’t know, but I was honest. I liked the way the Rastas looked. I don’t know anything about them. And you know what? I wouldn’t mind wearing a pair of shorts and flip-flops and hanging around the jungle smoking weed all day.”

*This article appears in the April 18, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.