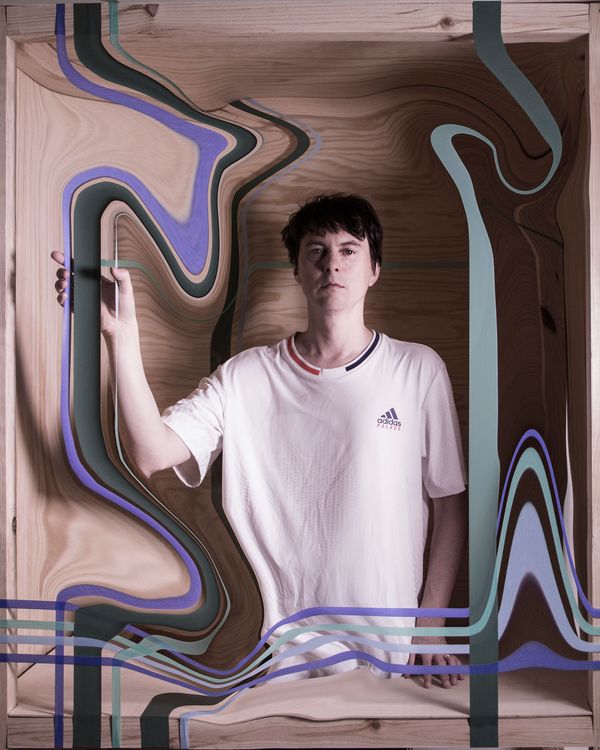

When Panda Bear’s record label sent out promos for Buoys, his sixth solo album, they politely asked that it be played “on the highest-quality audio system you have at your disposal,” rather than the computer speakers or those dangly earbuds that now serve as conduits to our music-listening habits, lest the album’s resonant low end get cut out entirely. So it makes sense that I go to meet Noah Lennox at the World of McIntosh townhouse in Soho, where an array of handsome, aesthetically assuaging blue-lit McIntosh amplifiers properly convey the fathoms-deep bass tones that pulse beneath the winsome surface of Buoys. “When you listen to Buoys on laptop speakers, it’s half the image to me because of all the stuff that’s going on at the bottom,” he explained as he reclined in a leather chair. “But it does feel like half the story in a way.”

Maybe making listeners pause to consider exactly how to first experience Buoys is one of Lennox’s strategies for pumping the brakes on all of our high-metabolism processing of information. Take a little time out to enjoy this, the request suggests, maybe on the couch instead of at your cluttered desk. Instead of looking at your phone while this plays, maybe just feel the music in the moment. At times on the album, Lennox even sings about looking up from the screen. Last year, he released a vinyl-only EP that one still can’t quite track down online to stream. As longtime fans of Noah Lennox or his other band Animal Collective might know, Lennox is a man of simple pleasures. As his most famous song plainly states: “I just want four walls and adobe slats for my girls.”

Buoys is Panda Bear’s most stark and minimal album since 2004’s Young Prayer, his ascetic, aching paean to his recently departed father. Yet the album’s closest comparison might be to 2007’s paradigm-shifting Person Pitch, in that it finds Lennox reconnected with that album’s producer, Rusty Santos, striking out for new land. That low-end is counterbalanced with his own acoustic guitar and his own choirboy vocals now run through a patina of Auto-Tune, a strange hybrid of acoustic and digital, light and heavy.

It’s also an album that finds itself in a position similar to that of its creator, looking ahead while also taking inventory of the past. This past month marked the ten-year anniversary of Animal Collective’s Merriweather Post Pavilion and with it attendant think pieces about the album’s place in indie culture. Last year, Lennox and fellow Animal Collective bandmate Dave “Avey Tare” Portner revisited their 2004 album Sung Tongs, playing the album in its entirety for a run of shows before thousands of devotees of the band. In 2009, “My Girls” sweetly spoke to that simple urge of a young father to provide for his new family; now the songwriter finds himself confronted with raising a 13-year-old. And maybe convincing her that dad’s music is cool and worth listening to.

Merriweather Post Pavilion turned ten years old this month. Does it feel that old to you?

Like a lot of things in the past, it feels really old and really not old at the same time. It feels like yesterday, but I guess musically, creatively, it feels closer. When I think of that album, I remember the times more than the music. I think because it was such good times making that thing. It was all easy-breezy the whole time. There was very little adversity in the process. Everything just worked out the whole time. And we have really good jokes from that time, some all-timer jokes for us.

Like what?

I can’t blow our cover.

Last year, you and Dave Portner performed Sung Tongs in its entirety for a string of sold-out dates. I had never known you guys to look back like that.

I was really reluctant to do it, but it actually turned out to be really fun.

What was it like revisiting that time in your life, back when you still lived in New York? [Lennox moved to Portugal soon after the release of Sung Tongs.]

Those were kind of the last days of New York for me, so they do have a special feeling in terms of memories. I feel like it was easier than I thought it would be to kind of emotionally get invested in those songs again. There are definitely things I would do different, probably more lyrically than musically, but it’s part of the reason I don’t like to listen to old stuff, because I’ll be like, I would have done that differently, or like, This could be improved.

You hadn’t really worked with Rusty Santos since Person Pitch, so how did you come full circle for Buoys?

It was kind of an instinctual decision on my part. I hadn’t seen him in six or seven years probably. We’ve sent emails to each other and just kind of said “What up?” every so often, and I was always aware of stuff he was working on; I was a big fan of the DJ Rashad stuff that he had done.

He was in Lisbon, so we hung out and he was telling me about stuff he was working on. And I had kinda just come off all the Sung Tongs tours. For those shows, I had to like retrain my hand how to play guitar. Tomboy was probably the last time I was really playing electric guitar a lot, and acoustic is just a little harder for my hands. It takes more muscles. And while I was practicing for Sung Tongs, I would write other little things. Buoys has a tuning that’s the same as Sung Tongs all based around the acoustic guitar.

Rusty told me what he was working on in Mexico City, making things like sad trap, Latin trap, reggaeton, stuff like that. And I was like, “I wonder what the stuff I’m doing would sound like kind of like synced with that?” So then we got together again.

So what does sad reggaeton Panda Bear sound like?

Buoys! I mean, I know it doesn’t sound like a trap record, but when I think about just the sonics of the thing, the architecture, it’s really similar to me. Trap to me is like an extension of dub, or kind of like a contemporary version of it, and then it’s a similar setup, as far as having a really low, deep thing and then skittery high-hat sort of stuff. And then there’s a vocal in it, so that changes things a little bit, but it’s how those few elements are treated that kind of like defines the space of the song. It’s sort of like Drake, where there’s nothing where the vocal is, so the vocal is allowed to kind of occupy this space by itself, but it’s closer to the higher register. And there’s really no bass guitar like in dub, there’s like nothing in that area. Those frequencies are just shoved deeper down.

My first impression of it was that this was the most Portuguese-sounding Panda Bear album yet, the first time I felt like life in Lisbon had seeped into the music.

I had never thought of that, but I like that. I mean, bossa nova was one of the first types of music, after stuff that my parents were into, that I — it was kind of like my own thing. Guys like Jobim, João Gilberto. I didn’t know about Tropicália until, like, way later.

On Buoys, you also use Auto-Tune for the first time. Was that coming from you, or was that a suggestion from Rusty? What made you go toward that?

I really wanted to have a single vocal, but I could never get it to sound pleasing to me or fit it in the mix very well. So when I told Rusty I was looking for something like that, that was his suggestion. He thought we could get something using that. Auto-Tune was the first thing where it sharpened the edges of my voice in a way that makes it sound a little bit thicker to me.

Did you find yourself looking at Future and Migos and stuff like that?

I did want to make something that felt like it was part of the conversation more so than stuff I’ve done the past five years or so. But I mean, that inspiration is not something new for us. Like, on the Spirit They’re Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished [the first Animal Collective record], we were into that song “Bills, Bills, Bills” by Destiny’s Child. It had like this skittery rhythm that felt really new for radio music at the time. Also that Aaliyah song with the cooing baby.

So all those rhythms, all the drum patterns that I played on that record were inspired by that stuff. So it doesn’t feel like a novel approach for me, though it does feel a little bit more kind of explicit this time around. I felt more warranted doing that because that’s just the landscape now.

Do you keep up with new hip-hop?

It’s more on the production side of it. That’s the stuff that is really juicy for me. There’s a lot of YouTube videos of Zaytoven where he’s just making stuff all the time. And the speed that he does it at. I dig how he goes about constructing the stuff. Swae Lee’s one of my favorites. I like Metro Boomin, too. Rusty is in that mold, like the way he works is in that zone, so all the bass stuff is just 808 samples. Zaytoven will do some playing, but it’s all very manufactured music. And Buoys was like … Rusty was really … well, the guitar was this thing that he was most kind of like, “Eh.” He wouldn’t say it, but he might have not wanted it there. He was really against any playing of any kind.

You have a teenage daughter now. Do you take any cues from what she’s into, or is there an aspect of what you do that she understands more?She doesn’t like anything that I do. My younger son Jamie might be kind of down for it in the future. I feel like it’s possible. But I think my daughter’s kind of on a trip where it’s like anything that dad is about or into can’t be cool.

So you just ruined trap music for her?

I don’t think it sounds enough like trap. The rhythms are so different, I don’t think it’ll ruin it for her. She’s mostly into Brazilian funk, which is what all kids are into in Portugal, where all the beats are like [he claps in a cadence like a jump-rope rhythm]. It’s all like that.

Was there a unifying theme to the lyrics?

I guess if there’s a common theme to all the songs, it’s either humility or it’s a love letter to humanity. I really wanted the listener to feel loved more in like a family way.

A few times on the album you mention screens, looking up from them and the like. In your mind is your listener an old guy, or do you feel like it’s more for your kids, or for someone younger than you that you’re trying to impart something to?

I definitely felt like I was targeting my kids and people of that age, mostly because I felt like an older person is crystallized in their way of thinking about themselves and about other people. I felt like the stuff that I’m talking about is most valuable for a young person to consider.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.