In 1999, before they were widely imitated, widely parodied, and finally old hat, the “bullet time” sequences in The Matrix were — what is a suitably retro phrase? — da bomb. Everything we thought we knew about movies (about the time-space continuum, really) was, in an instant, up for grabs. Here was proof that we could no longer trust our brains to process visual stimuli.

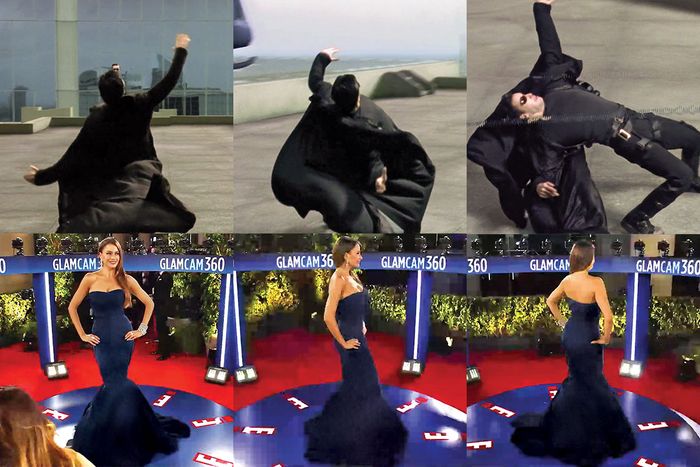

The technique was named for the disjunctively fluid shot in which Neo (Keanu Reeves) throws himself backward in slow motion, his long coat skimming the floor, as a bullet soars by him like a bead of mercury, leaving shimmering traces in the air while the camera simultaneously arcs around him in real time. The shot and others like it were devised because the Wachowski siblings wanted to use slow motion to achieve the graphic punch of still comic-book frames but also wanted to move the camera at normal speed. They wanted a spatiotemporal WTF. They got it from effects designer John Gaeta, who argued that since movies were just still images joined together, the scenes in question could be shot with 120 side-by-side still cameras set to go off serially within microseconds of one another. Space and time could then be cleft in twain.

People argue about bullet time’s antecedents, but everyone agrees that the first major use of the effect was in a Gap commercial called “Khaki Swing.” That was cool, but khakied swing dancers didn’t have the existential heft of The Matrix. Bullet time animated the Wachowskis’ philosophy, a mix of Gnosticism (overlapping with Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, which turns up onscreen), messianic Christianity, and Zen Buddhism. It digitized David Byrne’s cries of “This is not my beautiful house! This is not my beautiful wife!” But there was another vital component. The great bullet-time shots rely not just on fancy computer work and editing but on actors (not stuntpeople) executing jaw-dropping martial-arts moves in long, single takes. Martial arts plus bullet time represented Mind over Matrix.

In just a few years, filmmakers would have the computer technology to make the human body do anything at any speed, and they would do it so promiscuously that miracles came to seem cheap. Even the Wachowskis couldn’t recapture the magic, although they tried in The Matrix Reloaded with the “Burly Brawl,” in which a digital Neo fights off scores of digital Agent Smiths, all created in a computer with the burgeoning motion-capture technology. But the “Burly Brawl” had surprisingly little kick. It reminded me of the scene in David Cronenberg’s The Fly in which Geena Davis tries a steak that has been teleported from one pod to another and concludes that it “tastes funny.” So much of bullet time felt tangibly real.

The last time I saw “classic” bullet time, it was used on the E! Network’s Golden Globes red-carpet show to give audiences a better view of the fashion and celebrities on display. Meanwhile, most big-studio live-action movies are no longer different in essence from animated ones, which are themselves becoming more three-dimensional, more “real.” In retrospect, bullet time seems like the crossover point, the bridge between the human and the not human, the real and the synthesized. It helped us get comfortable with no longer trusting our own brains.

*This article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From This Series

- The Beatific Imperfection of Keanu Reeves in The Matrix

- How The Matrix Got Made

- The Matrix Taught Superheroes to Fly