Women writers are increasingly recognized as the dominant force in the contemporary literary landscape. We certainly don’t need an occasion to recognize and recommend them, but March — Women’s History Month — is as good a time as any. Vulture asked ten women writers (all releasing their own books in March) to choose two must-read titles apiece. Read on for selections from Amber Tamblyn, Taylor Jenkins Reid, and others.

Lisa See, author of The Island of Sea Women (March 5)

I’ve been revisiting novels that I loved when I was a kid but as an adult have read very differently. One that particularly struck me is Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. Today I see the influences of Alcott’s father, a major figure in transcendentalism and seriously pathetic money manager.

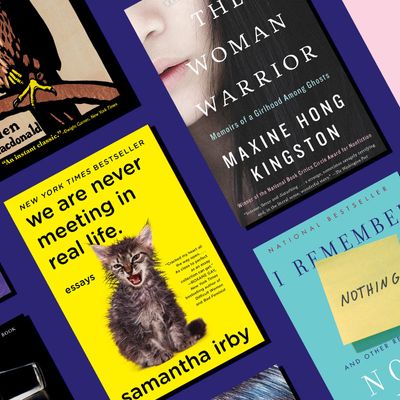

Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior was groundbreaking in many ways. By blending autobiography, myth, and history, she revealed the experience of Chinese immigration to the United States in a way never before seen. Hong’s “talk stories” also helped launch the careers of many — most? All? — Chinese-American writers working today.

Amber Tamblyn, author of Era of Ignition: Coming of Age in a Time of Rage and Revolution (March 5)

Irby is one of our country’s most fierce and foulmouthed authors, whose literary takes on sex, family, and the body are unique in their comedic resonance and full gut-punch power. The best thing about this book, and all of her writing, is that the reader is made to feel like they are taking a master class from their best friend, and you feel right at home with Irby’s stories and points of view while also being completely in awe of her craft and wit.

Because I want to recommend every single poetry book this author has written but can only choose one, I’ve decided on her first, a collection of the many poems the author wrote early on in her career. McKibbens is one of the most admired and copied (sometimes even plagiarized) poets in recent history, and this is due to her blistering work as both a writer and performer. Her poems cover everything from severe mental illness, to the experiences raising her five children, to a brutal childhood upbringing. McKibbens is, in the truest sense of the term, real required reading for anyone looking for poems that will break you wide open and shatter you onto the floor.

Halle Butler, author of The New Me (March 5)

Set in Paris in the 1930s, this novel feels, in some ways, like an answer to Tropic of Cancer. The narrator wanders the streets and cafés, paranoid that she will be recognized — either correctly (as the tragic drunk) or incorrectly (as the uptight English woman). She plays dumb with the grifters who mistake her for rich. She tries to keep her emotions in check. This is my favorite of Rhys’s novels. Expect catharsis.

Yeah, I was going to try to not pick this one, but it’s my favorite book. The first scene: Edith is packing her family’s Manhattan apartment (to move to Pennsylvania, which she thinks is what her husband wants) and finds a crumpled shirt in her son’s drawer covered in a crusted substance (ahem) that she tells herself, cheerily, must be crafting glue. The sick delusion and humor only get better from there. Enjoy!

Mary Fleener, author of Billie the Bee (March 5 in paperback)

Pond has a soulful way of adding pizzazz to a common story in an uncommon way. The bizarre menu of people that work with her at her small diner becomes a revolving door of crime and indelicacy, but Pond recognizes their humanity, and as the story unfolds, you just have to love them all.

Like a mad scientist, Ferris takes the chemistry of comics to a new, innovative level with a drawing/design technique that is sensuous and gamy. It’s a whodunit murder story observed through the unflinching gaze of an 11-year-old girl, with a sinister background story that will knock your socks off.

Taylor Jenkins Reid, author of Daisy Jones and the Six (March 7)

Miller’s work is audacious in the most thrilling sense of the word. She’s reimagining ancient myths — stories we have been telling ourselves for millennia — in bold and inclusive ways. Miller’s version of Circe, the goddess/witch, actively reclaims her story from the men who have told it before.

I Remember Nothing was Ephron’s last book, and you can feel it in the subjects she tackles, most specifically her two stunning lists “What I Will Not Miss” and “What I Will Miss.” All of her work is excellent, but her last one is a great place to start. Nora Forever.

Candice Carty-Williams, author of Queenie (March 19)

Seeing myself in a book is … uncommon. Americanah, though, is where I saw an undeniable version of myself in the pages. As much as it’s about the endurance of black love — from Nigeria, stretched from the U.S. to the U.K. — it’s about taut relationships, divisive politics, identity, and hair.

Bridget Jones’s Diary was the first book that let me aspire to be the woman I’ve become: Bridget is single, can’t take herself too seriously, smokes too much, falls over often, and makes bad decisions regarding men. She might be a slim, posh blonde, but she speaks to so many women.

Polly Rosenwaike, author of Look How Happy I’m Making You (March 19)

Jenny Offill called this memoir about Cusk’s entrée into motherhood “a secret handshake among new mothers.” I would like to see it forthrightly handed out to new parents, along with the basic literature on care and feeding. Incisive and bracing, it’s an antidote to all the sentimentalities about what it means to become a mother.

A gift-book-size book that delivers the gift of feminist consciousness. Read Cusk to navigate babydom, and then Adichie to raise girls attuned to gender inequalities, “Feminism Lite,” and “Because you are a girl” bullshit. This eloquent and hopeful manifesto is a reminder for women, too, that “there is no social norm that cannot be changed.”

Claire Harman, author of Murder by the Book: The Crime That Shocked Dickens’s London (March 26)

Wollstonecraft’s impassioned plea for the rational treatment and equal education of girls never fails to surprise me with its razor-sharp analysis of male-female relations and its cut-to-the-chase proposals: “Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it, and there will be an end to blind obedience.” There’s an amazing urgency about it that is incredibly stirring; she was the first and best philosopher of feminism.

How did a totally obscure Yorkshire parson’s daughter, discouraged on every front, manage to write a novel that has affected so many people so powerfully since it appeared 172 years ago? Because she felt all the turbulent emotions of her heroine, and burned with a sense of injustice, “like any rebel slave.” And because she was a poet and master storyteller. I love this book that landed like a bomb in Victorian literary culture and continues to tick: shocking, thrilling, and endlessly re-readable.

Mira Jacob, author of Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations (March 26)

I first met Marlys Mullen, the bungling, dreaming, self-assured, bucktoothed teenage girl at the center of Lynda Barry’s comic strip, “Ernie Pook’s Comeek,” in the early ’90s, and she settled inside me like a new bone. I hadn’t known before that characters like Marlys could exist, that they were worthy of existing. It was my first inkling that lives that looked even slightly like mine could matter. So I was thrilled in 2016 when Drawn and Quarterly published the expanded and updated version of this classic. Barry’s devotion to the small moments of a life that is outwardly unremarkable, her ability to let a story grow wild and raw between frames, is remarkable.

I reread portions of this visceral, challenging, beautiful collection of short stories the minute I need to feel brave. Bhuvaneswar’s deeply discerning core, her willingness to tell the hard part of the story, to imagine the fullness of queerness, color, survivorship — us! — is like a clean hit of oxygen. It helps me remember why writing matters.

Laila Lalami, author of The Other Americans (March 26)

This book! If you’ve ever lost a loved one but didn’t have the words for all the emotions that hit you, you’ll want to read it. Helen McDonald writes about her attempt to adopt and train a goshawk — a particularly vicious bird of prey — after the sudden death of her father. What does falconry have to do with grief, you might wonder. That is the beauty of this memoir. It draws unexpected connections between animals and humans and creates a whole new vocabulary for exploring loss.

This year, we’re blessed to have a new book by the greatest living American writer — Toni Morrison. It’s a collection of essays, speeches, and commentaries, many of which never appeared in book form until now. She has such a keen eye for the distortions and hypocrisies that characterize discussions of race and gender, and a formidable talent for getting to the heart of the matter. I’m so excited to read it.