In January of 1992, Gregg Araki went to Sundance with a splashy, gorgeous, middle-finger-flying-in-the air film: The Living End, his raging, morbidly funny road-trip movie starring two unknowns as HIV-positive men who go on the run after killing cops. The spirit mimicked the form — Araki made it on almost no money, guerrilla-style around the streets of Los Angeles. The Living End became a part of a cohort of films and filmmakers infused with the urgency of the AIDS crisis, like Todd Haynes’s Poison and Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning, which won prizes at Sundance the year prior. But just as Sundance has grown up over the intervening years, so too has Araki: His new Starz show, Now Apocalypse, has a glitzy budget and an ad on Sunset Boulevard — a far cry from the days of shooting in the early morning on Melrose without permits. Araki himself has left the post-punk rage of an AIDS-ravaged era in favor of an optimistic, New Age serenity.

Still, Now Apocalypse contains all of Araki’s hallmarks: beautiful youth, sexual fluidity, and a possible alien invasion. The freewheeling nihilism and punk ennui has been banished in the California sunshine, and instead, his characters — the “ever-oscillating” Kinsey 4 Ulysses (Avan Jogia), his best friend and aspiring actress Carly (Kelli Berglund), and his straight, aspiring-screenwriter roommate Ford (Beau Mirchoff) — are filtered through a vape pen and an Instagram-ready lens. The kids are still lost in a haze, but they’re super-chill about it.

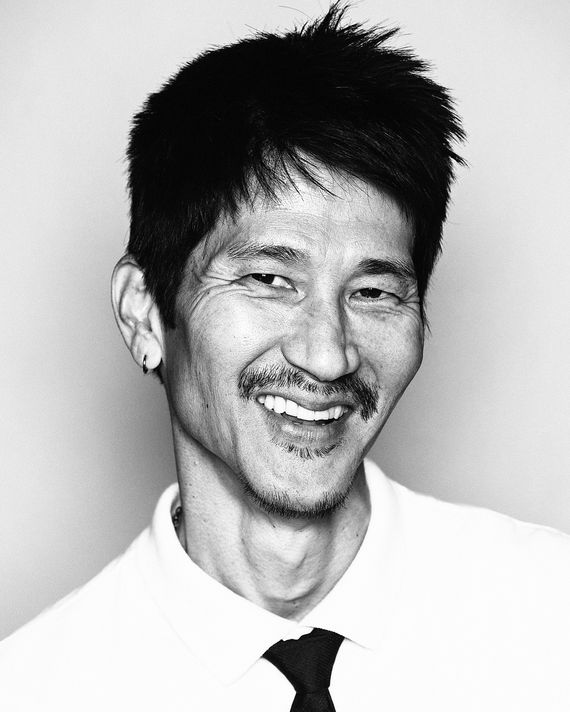

In person, Araki, 59, is blithely content. “People are always so shocked when they actually talk to me, because they think from my movies that I live this crazy, like, Oh yeah, he’s like taking a lot of drugs and going to sex parties,” he says over lunch in New York. “I like living life and really be in life.” In a wide-ranging discussion, we talk about Now Apocalypse within the context of his oeuvre, doing a post-Trump pass on the script, gay-baiting in Riverdale, and what’s queer about cinema now.

Where does this fascination with aliens and the end of the world come from?

The show is almost my vision in a purified form. It’s very much my brand. And part of that [is the] apocalyptic mood. I remember when I did the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, it’s this thing about a time in your life when your emotions are so heightened that it almost bleeds into the universe. Your boyfriend cheats on you and it becomes this catastrophic event. It is like the world is ending. And that sense of doom is partly subjective, but then becomes more a part of the kind of Zeitgeist. And that’s why Now Apocalypse is so weirdly resonant and fitting for today, because the world has very much come to that place. Karley [Sciortino, the co-writer] and Avan [Jogia] both talk about the idea that the world now is much more like the world of my movies in the ’90s than it was the ’90s. The world has become a very kind of Nowhere — particularly with young people — the sort of utopian world of sexual fluidity and multiculturalism. The millennial generation is much more like Nowhere than young people were at that time. At the same time, unfortunately, this sense of apocalypse and chaos and the madness of this world that we live in is so much crazier now than it was in the ’90s.

Even during the AIDS crisis?

Well, that was actually more like late ’80s, early ’90s, which was very much my early, early movies.

Like The Living End.

The Living End and Totally Fucked Up. That particular sense of doom came from a super-dark place. When I made The Living End, I was living in the tiniest apartment ever in Los Angeles. I had no money. I’m just like this artsy, punk-rock kid making this crazy movie about AIDS and these two hot guys with guns running around and killing. I look back on it now with incredible fondness, but I was so angst-ridden, listening to the the Smiths all the time. Just that feeling of, “Oh my God, why don’t I just die today?” I was feeling so hopeless and so miserable. When you’re in the middle of that fucking chaos and all that misery and all that fucking shit and I can’t even get out of bed — everything’s fucking spiraling. When you look back on those years, making The Living End, those were like the fucking coolest times, but you don’t see it when you’re there. And I see it now.

My understanding was that shooting The Living End was very fly-by-night.

The definition of fly-by-night. We had no permits. We had literally nothing. People weren’t being paid. We were just eating Chinese food out of a take-out box that Marcus [Hu] got from the restaurant down the street. It was just this weird labor of love and everybody was there because they believed in it. It was me and a 16mm camera. I remember being in the backseat of a car with my camera, and just driving in the middle of nowhere with those two actors, with a producer holding a flashlight to light the scene. It was that kind of punk-rock project. We were young and dumb and just had nothing to lose.

Doom Generation was just [a] fucking insane shoot. It was all nights; Rose [McGowan] and Johnathon [Schaech] hated each other, they were fighting the whole show. Every day was so much chaos, so much craziness. The second day of Doom Generation was the Northridge earthquake and we had to cancel our shoot that day. It was just one insane thing after another. It was, like, crazy kids doing crazy shit. We live to tell the tale. We’re still here. We’re still kicking.

Did you think that you would die young?

People are always so shocked when they actually talk to me, because they think from my movies that I live this crazy, like, “Oh, yeah he’s like taking a lot of drugs and going to sex parties.” I’ve never had this death wish. I’ve always been very interested in alternative culture and the rebellious, different, outside-the-mainstream thing. But I’ve never viewed myself as being self-destructive. I don’t take drugs. I barely drink. A lot of people who are really driven to drink or like alcohol or drugs or whatever — they’re trying to escape. They’re trying to anesthetize themselves in some way. And I’m almost the opposite. I’m trying to be awake. I’m trying to be in the moment and live the moment and actually process it and use it for what I do. I don’t want to be dulled in the senses. I like living life and really be in life.

Do you feel Now Apocalypse is more optimistic compared to your early work?

Definitely. I’m in my 50s now and I’m in a very different place than I was when I did The Doom Generation. I was feeling those feelings of confusion, not knowing who I was, that angst of those early movies. The Living End was a diary for me. It was me spewing all of my dread about AIDS and the holocaust. And the older I’ve gotten, I’m happier than I’ve ever been. You turn 40, you turn 50, you’re just much more comfortable in your skin, much more aware of who you are. I live a life of literally, like, no drama. The confusion of growing up and the confusion of who am I, what am I doing, what am I gonna be? You grow out of it. You become the person you’re meant to be.

How did the AIDS crisis inform The Living End?

Well, thankfully, it’s different for the current generation. I hope that nobody ever has to go through what we went we through. People in your generation can’t even understand what it was like to be young and gay and living in the late ’80s, early ’90s. It was a war zone, where you would feel like there’s a target on your back and people are just dropping dead on the streets. It was a nightmarish, surreal thing to live through. Also, it was so politicized. It was like, I’m literally being exterminated. I’ve been targeted for this genocide. For people who lived through it and survived, it’s something that you really carry with you. That’s why I, you know, I’m so proud of The Living End, because it’s important people don’t forget that.

The ending of The Doom Generation feels very current to me. A group of neo-Nazis rape Rose McGowan’s character and then castrate and kill James Duval’s.

My early films like Doom Generation and Totally Fucked Up have these themes of violent gay-bashing in them, which was very much a part of that ’90s sensibility of, like, You’re queer and you’re visible and now you have a target on your back, which still exists today, but it’s certainly better than it was in the ’90s. But it’s interesting, we wrote Now Apocalypse in the twilight years of the Obama era. And that’s why this show has this weird optimistic confidence to it, because the world felt as if it was really progressing and things were not perfect but so much better.

Yes, there’s a poptimism about it.

And then 2016 happens, right, and I did a post-Trump pass of the script that was literally, like, things get a little bit darker. One of the scenes [that] got added was the fag-bashing scene, the scene where Avan [Jogia] and Tyler [Posey] are kissing outside the coffee shop.

In the pilot.

And the fag-bashers drive by. Just this sense that the world is a little bit more dangerous than we think it is. That was a post-Trump addition. I do think that’s why the show is actually so important, because there’s this backlash against all the progress that we made. Let’s put the black people back in the back of the bus. Let’s put the gays back in their underground bars. Let’s make America oppressive again. And that’s why I think it’s so important for a show like Now Apocalypse to come out, because it’s really about, We can’t go back.

Something about the anger and sense of nihilism of those ’90s works really resonates with me now, because we feel very much on the brink. Do you feel at all vindicated by that sense of nihilism? I know that’s twisted in its own way.

We live in really scary times. It’s one of the things I was thinking about — about the show, because all I do is think about the show. When we were driving here, it’s cold and snowy. Even though it’s March, it feels like the dead of winter. And Now Apocalypse is so pop and bright and odd and sexy, and there’s a kind of psychedelic feeling. There’s a warmth to it. And I just feel like the world really needs it. It’s an antidote to all of this darkness and all of this chaos.

What do you think of queer cinema right now?

You mean queer cinema in terms of the New Queer Cinema of the ‘90s or …

Right now, at this moment.

I don’t know what you consider that. I mean, is Bohemian Rhapsody queer cinema? To me, New Queer Cinema was The Living End, Swoon, Poison, all that stuff — 1991 to 1994. It was really a specific moment in time, relating to ACT UP, the AIDS crisis, this handful of five or six filmmakers making movies. It was a very specific thing that happened in culture. That, to me, is like the queer cinema. I mean, having gay characters in movies — is Will and Grace queer cinema? I don’t consider that queer cinema.

I wouldn’t either.

All of those filmmakers, all of us have moved on and done other things and worked in other genres or wrote other kinds of movies. We all are on our own separate path. And the thing about New Queer Cinema is it was never really orchestrated. It was just an accident. It was just a bunch of young artists really being impacted by AIDS and really like, “Holy shit, this is fucking insane what’s happening right now.” All of us, as artists, processing that and responding to it. And then we all get older and move on and do other things. That’s queer cinema. Queer characters in movies is not queer cinema.

So, what do you think of then …

What do I think of queer representation? I think that’s awesome. There’s always room for more, and there’s always room for different stories, but it’s great that there’s so many LGBTQI characters everywhere. We’ve come a long way.

Well, let’s be more specific: What do you think of movies like Bohemian Rhapsody and Love, Simon?

I feel bad, I’ve been so busy with the show, I’ve seen hardly anything because I’m in a salt mine working on this. I literally, last night watched Bohemian Rhapsody on the plane. Obviously it’s whitewashed for what’s going on, but it didn’t shy away from the idea that [Freddie Mercury] was bisexual and had sex with guys. It wasn’t like it was completely out of the story. I have more of a problem with biopics in general, because they’re just such a weird genre. It’s not a genre I’m terribly interested in. To its credit, I think that they dealt with it. And for a Hollywood mainstream movie that made, whatever, hundreds of millions of dollars around the world, good for them.

I guess what I’m trying to get at is, what you think about the mainstreaming of queer stories. Do you think something is lost in that process?

I feel like it’s interesting. We premiered the show at Sundance. The Living End was my first film.

In ’92.

’92. I mean, you should have been there. You weren’t born yet, but people’s jaws were on the floor. It was such a crazy, punk rock, underground, 16 mm, weird movie. It made a splash. And then, to go back there in 2019 with Now Apocalypse, which is very much the same vision. Very unbridled, very unapologetic, straight out of my imagination and to the screen. And it’s a Starz show. It’s gonna be seen all over the world. There’s billboards on Sunset Boulevard for it. It just really struck me when I was at Sundance, like, how far the world has come and how much culture has changed. Because, in 1992, that was before Will and Grace, before Brokeback Mountain, it was just shocking to see two guys make out. And now, in my show, you have Avan Jogia and Tyler Posey — these two hunky teen-idol kids — and they don’t bat an eye, there’s just in an alley making out.

In much of your work, there’s a fascination with a hunky, straight white guy. Where does that come from?

The thing that’s been a huge influence — probably somebody has done a dissertation — is the impact photographers like Bruce Weber had on our culture and on gay culture. The Living End [is] so Bruce Weber-y, in terms of male objectification. I don’t think about it when I’m writing, but that icon of the hunky straight guy, the kind of Abercrombie guy, is just part of my consciousness. That’s one thing about the show, we can subvert it or play with that stereotype. And that’s why I love the Beau character so much — I actually wrote that part with Beau in mind — because he’s so that icon but so not that icon. He’s this rugged, corn-fed all-American guy, but inside, his character is basically a needy girl. He’s the emotional one. He cries a lot. It was so fun with that character, to be able to play around with the trope of all-American masculinity.

It was very important to me to have a lot of people of color in the show and that whole Bruce Weber-y aesthetic, which is a huge influence on me, but also to be able to react to it. And so, the objectification of that symbol. But at the same time, all of the guys of color are equally objectified. The idea of questioning the whole notion of objectification, particularly queer objectification. Does that make sense?

I hear what you’re saying. I’m curious then: How do you see race operate in your work? Do you just see it more through a multiculturalist framework?

My films have always been, almost from the beginning, trying to be as multicultural as possible. Because I live in a multicultural world. And so that’s always been a big part of my sensibility. Designers need a creative concept. So it’s really the objectification of people of color or something that is part of the reeducation process almost. Like, what is desirable? That is something the show addresses.

Have you felt that race has not been a particularly impactful force in your life?

Not in a negative way. I guess there’s also more context — I’ve never felt like it’s held me back. In many ways, for me, particularly what I do, being Asian and being queer or whatever I am, is actually a plus. Because I have a different voice and I’m coming from a different perspective. So it automatically makes your work more interesting. Rather than just the same old white, straight, patriarchal point of view that is the status quo.

What were your own experiences like exploring your sexuality when you were this age?

When I was in film school in the ’80s, I was like a super-artsy, punk-rock dude. I wore thrift-store clothes and had this asymmetrical haircut. I was really into Godard movies, like, I was that guy. I was not out. Which is, to me, super-telling. That’s what the ’80s were like. Somebody like that was still not out. I eventually came out, in a way. I think that that’s, again, how far we’ve come. A kid like me today would absolutely be out of the closet. Kids are coming out when they’re 13, 14, 10.

In the wrestling episode of Riverdale that you directed, I was hoping you could explain why they were wearing T-shirts under their singlets?

Network note. Archie was not. And, I mean, hello, he’s the lead of the show. He was the most … heh. Archie wasn’t wearing a T-shirt. Roberto [Aguirre-Sacasa] wanted like a mix. But there was a lot of singlets and a lot of skin. It was like the gayest thing I’ve ever seen, and I’ve done a lot of gay movies. I was like, “Whoa, this is pretty gay.”

It was shot very sexily.

Why they hired me, I guess. But Riverdale and Teen Wolf and all those shows, they’re all made by these super-gay creators, right? And they all have these super-hot guys in them. But they’re a tease because all they ever do is get naked, take a shower, slap each other. Like, I get it. I get that there’s this gay sensibility at work, and they’re objectifying this guy to a ridiculous degree. But they feel almost frustrating.

Like, we’re getting blue-balled.

Yeah, a little. Right? Aren’t you? I mean, I dunno. But that show is a network show. It’s on the CW, so they’re very “This is what we can do.” But our show, we can do whatever we fucking want.

It’s like they’re gay until the bedroom.

I mean, [Archie] was kissing some dude this season. Anything they can do to gay-bait the audience, they do. But they all do it. It’s like, what’s his face, Nick Jonas. It’s just like, “I’ll fucking pose in my underwear, grab my dick, show my ass.” It’s like, “Whatever, I’ll do anything. But I’m still straight.” If you wanna get super queer-theory philosophical, it’s fetishizing a straight guy to a ridiculous point. Where it’s like, our show, we give you that. Avan’s what he is — sexually fluid. We can show the relationship and not have to go through all these machinations.

But to bring this back, Beau is a hot straight white guy who you fantasize about but that you can’t get with.

Yeah, but I think that’s actually written into the show in a way. It’s almost like a comment on it. You won’t see that on Riverdale. I’m not gonna comment on [Archie’s] objectification in the way he’s fetishized.

Do you think that’s a network thing?

It’s a mainstream show. It has a different demographic. I love Roberto, Riverdale’s great, I do think it has a huge gay audience, and good for them. And I think that it’s a young audience that maybe is just one toe out of the closet. That’s fucking great for them, but that’s not what our show is. We have queer characters; they have queer sex. They can take their clothes off.

What is it about youth culture that fascinates you?

When you’re young and figuring shit out, you’re very much a question. Everything in life is uncertain. You don’t know who you are, what you’re gonna do, what sexuality you are. You’re just a ball of confusion. Which is, for me as a filmmaker, so fascinating. And there’s just so much dramatically and dynamically that can happen. Like, the characters of Now Apocalypse, anything can happen to these fucking people. They could be fucking president. They could be a fucking heroin addict. We don’t know what’s gonna happen to these these fucking kids. And that’s so, creatively as an artist, such an awesome canvas to paint.

How do you feel like nudity has operated in your work?

I feel like my films are terrible pornography, because they’re not meant to titillate. It’s not porn. It’s not meant to be arousing, although they’re sexy. I feel like American movies in general are so puritanical and they really avoid sex to a weird level. So for me, sex in movies is when you really get the truth of these characters. You get to know them in the most intimate, personal way possible. If you think about it, everybody has this public persona. You and me sitting here at this table talking. And then there’s the persona that you have with your friends. But then there’s the you that people who you’ve slept with know, and that’s a different person. That’s the secret. Even if you’ve just had a one-night stand with somebody, you know them in a way that even their best friends don’t. As a filmmaker, that’s what I find really fascinating — those personal, private moments.

Do you think that’s a truer or more vulnerable self?

Yeah, definitely. It’s when your defenses are gone, your masks are gone. I mean, you’re literally physically naked, and also kind of emotionally naked. And that is something I’m really, really into. Again, it’s not about titillation. When Nicole Kidman is naked in Big Little Lies, it’s all I’m looking at. Like, “Wow, Nicole Kidman is naked.” It’s all you’re thinking about. And that’s not the way it works in my shows. I feel like you forget that they’re naked. It feels kind of natural.

How do you feel about being designated as a cult favorite?

I mean, I’m just happy to be here. I’m happy that Starz pays for my lunch. It’s weird because it is a little bit of a backhanded compliment. It’s a little ghettoizing, but I understand. My definition of success is, I still have kids coming up to me. We just did the premiere of the show in Hollywood last night, and these kids come up to me and say, “This show means so much to me.” Like, “Your movie means so much to me.” And that is valuable to me. The fact that you’ve really touched somebody and made a difference for somebody and they really, really get it, that means more to me than, like, “Oh yeah, you sold a hundred million DVDs” or whatever. That’s not as rewarding. Because as an artist, that’s what I’m really about. Saying something and knowing that somebody out there is going to get it.