It seems like an easy enough ask: Two brothers, about ten years apart in age, are house sitting for their mom. All they have to do is watch the house and spritz some water on her plants. But the simplicity of Sam Shepard’s True West soon turns it into a masculinity crisis — of faith, of fear, and of Hollywood images. In the revival, running now on Broadway, Ethan Hawke plays the grizzled older brother Lee. Paul Dano plays his bespectacled little brother Austin.

Before he died in 2017, Shepard asked Hawke to star, stressing that he wanted the revival to be truer to the idea that the brothers are not interchangeable, as other productions have cast them as. Here, Dano spends most of the show being pragmatic and harried; Hawke’s performance is big, loud, and gratifying. He shotguns beers, kicks over chairs, uses a golf club to thrash a typewriter. His Lee is different than his version would’ve been 20 years ago, and his own read on the play has changed from when he first saw it as a teenager. “The idea of True West is a kind of manifesto of the evils of manifest destiny, and the joke of what Western mythology — meaning like Western L.A. Hollywood Western iconography — the great lie of what that is is eroding at these men’s souls. I didn’t even get that when I was a kid. I just thought it was funny and wild,” Hawke says. “I didn’t really see the larger metaphor of men left in charge of their mother’s house, men who forget to take care of the plants, are all gonna end up on the desert. All that stuff resonates in a way, in 2019, that it did not in 1984 when I first saw this play.”

Before a recent show, photographer Brigitte Lacombe — also a friend of Shepard’s — followed Hawke’s True West rituals. “She took the really iconic picture of Sam that’s on the cover of all his plays,” Hawke says. “It was kind of wonderful to have her backstage as kind of a representative of his spirit, watching us.” Hawke talked Vulture through the shots.

“When you’re doing eight shows a week, the life of an actor becomes very similar to the life of an athlete,” Hawke says, “in regards to being ready to go onstage at 8:06 every night, or whatever it ends up being.” True West is a physically taxing show: For two hours and 15 minutes, Hawke and Dano stalk, chase, and tease each other around the stage. Often their arguments turn into shouting matches that are heavy on the body and voice.

“One of the things that is interesting about not going to a theater school and getting a proper education about theater the way that all those British actors have is that I feel like I’ve been playing catch-up my whole life about really understanding how to prepare,” Hawke says. One way he prepares is a pretty loose preshow ritual. “This wonderful vocal coach gave us this warm-up, and one of the ways that Paul and Gary [Wilmes] and I all get in sync before we start the show is we goof around onstage doing these crazy vocal exercises. We always mean to play football, but we end up joking around, talking and doing these weird vocal exercises that make us laugh and get us ready.”

Another of Hawke’s preshow rituals includes a tribute to the playwright. Shepard first book was titled Hawk Moon and Hawke has a fake-ink crescent applied before every performance. “I think in his early 20s, he had a little hawk moon tattooed on his hand, a little green sliver of a moon. The first sliver of moon in November is sometimes called the hawk moon. I’ve always been fascinated by it because he writes about that moon which usually happens on his birthday, which is November 5. Mine is November 6,” Hawke says. “There’s something about this play that feels directly distilled from his heart, his brain, and so I wear that tattoo for the run in a kind of homage to the playwright.”

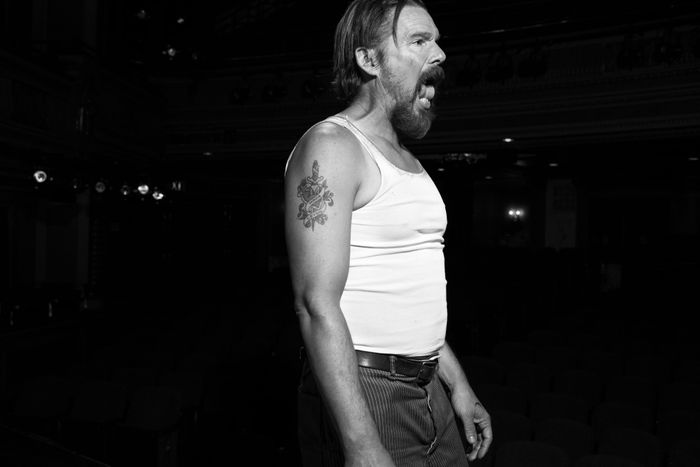

Hawke also pays close attention to his costuming details. His character Lee is the older brother, a smooth-talking drifter who’s trying to sell a half-baked idea for a screenplay. He wears a wifebeater under his bedraggled shirt, and has grown a gnarly mustache. Hawke wanted to keep Lee’s look authentic: “My character comes back after spending three months in the desert and I needed a tan for when my shirt comes off late in the play. I wanted it to be a farmer’s tan,” he says. “And so this guy, Tommy, paints me, gives me a cowboy tan every night.”

In the famous Broadway run in 2000, John C. Reilly and Philip Seymour Hoffman alternated roles, a testament to how unclear it becomes, in the climax, where one brother’s damage ends and the other’s begins. Hawke originally auditioned for that 2000 production when he was in his 20s. “I was always told that Sam Rockwell and I were the next choice. We auditioned together for that production,” he says. What does he remember about reading for it? “That they were fools not to cast Rockwell and I,” he laughs. “I remember that it hurt not getting it. That’s what I remember.”

Late in the play, the tension between the brothers boils over into a brawl, where Austin wraps a phone cord around Lee’s neck. Hawke and Dano practice it in a fight call before every show. “The unfortunate thing about fights is the more you practice them, the better they get, the more out of control they can seem,” he says. “There’s a great quote by Sam Shepard where he’s asked what his contemporary influences are and his answer is the rodeo. I’ve always loved that, and I know that what he wants from the finale in the play is to be a little bit of a rodeo.” By the time of the fight, the stage —a bright, kitschy suburban kitchen — is a mess of toasters, toast, dead plants, and all of the brothers’ demons. “Sam used to feel like everybody knows exactly what’s gonna happen next, and he was always trying to come up with a little madness, a little spark of insanity, something unexpected. So we have a shit ton of variables in our fight: There are beer cans on the floor, silverware, and wine bottles and cards and toast and golf balls and — I mean, if I could only show you how cut my hands are.”

All those props make the scene harder to get right. “We have to work really hard to make sure we actually feel like the other one is not trying to hurt us, so that Paul and I can maintain our friendship,” Hawke says. “I don’t know if you remember being a kid, but even when you’re play fighting, play fights usually end up in people really fighting. When the audience comes in, the adrenaline kicks up tenfold, so the more intimate it becomes with nuances of how to fall and how to punch and strangle and pull.”