Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible. See his picks from last month.

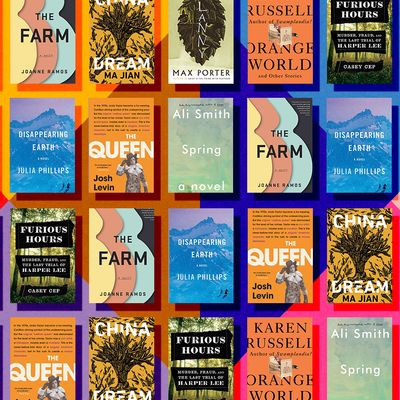

There is the rageful noise of news and politics, and then there is the slower pace and synthesizing power of fiction. Smith’s seasonal quartet of novels — this is the third of four volumes — bridges that distance by speeding up the work without sacrificing the author’s brilliant characterization and language. Spring is her most political volume, focusing in part on the work of a British immigration officer and a tween with the magical power of turning people compassionate — something Brexiting Britain needs as much of as we do.

This deep dive into the true-crime saga Lee ultimately failed to write is itself exemplary literary true crime — literary not in being half made up, like In Cold Blood, which Lee helped Truman Capote research, but in being about literature itself. Though the author of To Kill a Mockingbird appears rather late in the game, after we know everything we can about the devious rural preacher Willie Maxwell, Cep closes in on this book’s central question: Was Lee too timid to match Capote’s feat, or just too honest? Gripping and meticulous, Cep’s work doesn’t make us choose between fidelity and style.

What if you could write about a corporate patriarchal dystopia without recourse to mythologies or bonnets? What if you could just amp up the way we live now? Ramos brings us the perspectives of four women involved with an innovative retreat that houses and surveils surrogate mothers, a.k.a. “Hosts,” for the wealthy. Predictably, the walls close in on our three heroines — Reagan, Lisa, and especially Jane, a Filipina ex-nanny who’s had to leave her infant daughter behind. But the creepiness builds so subtly, so realistically, that The Farm never feels preachy, just terrifyingly true.

Speaking of real-time dystopia, here is the distillation of China right now: a weary population being forcefully remade by the dictatorial Xi Jinping into consumers of what he calls “the Chinese dream.” The exiled novelist Ma Jian, whose very name is banned in China, slyly co-opts Xi’s concept for the story of an earnest and corrupt bureaucrat, Ma Daode, who hopes to create a device that will help his countrymen forget their hardship and generational guilt — beginning with his own. Ma surreally collapses past and present, undoing Xi’s work with every ironic reversal and juxtaposition.

Porter’s second novel is the story of a missing boy in the way that, say, Hamlet is a murder mystery. As in his first novel, Grief Is the Thing With Feathers, Porter plays with England’s myths in the service of exploring humanity, community, and grief. Our omniscient narrator, an earth spirit named Dead Papa Toothwort, guides us among the gossips, scapegoats, and broken hearts that emerge during a search for the titular boy — a puckish spirit himself, recently transplanted from London to this suburbanizing town. The style and soul are what matter here; Porter’s is utterly unique.

Reminiscent of Russell Banks and, more recently, of Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, Phillips’s polyphonic debut novel takes on the challenge of a setting almost impossibly remote, but still teeming with people and their troubles. Two girls disappear near the shore of the Kamchatka Peninsula (as far east as Russia goes), and Phillips proceeds to track inhabitants in some way connected to the crime over a year, weaving a net as taut and intricate as any thriller plot but rich in detail about relationships, historical scars, and the specific and universal trials of being a woman.

Few writers move so deftly between forms (novel and stories), settings (Florida and elsewhere), and genres (realism, horror, dystopia, you name it) as Russell, a gorgeous writer as hard to pin down as she is to put down. From “The Prospectors,” about a couple of Depression-era lady grifters who end up at the wrong ski lodge, to “The Gondoliers,” set in a future sunken Florida both terrible and beautiful, Russell can be intimate, concise, and vividly entertaining while handling themes of epic global urgency.

Years before Willie Horton and Trump’s litany of immigrant murderers, there was Linda Taylor, the “Welfare Queen” of Reagan’s political attacks — an example not of the abuse of public benefits but of the way politicians can distort horrific outliers into racist scapegoats. Taylor was a sociopathic manipulator and possibly a murderer. Levin shows that, if anything, her crimes say more about the injustice of her youth as a biracial Alabamian than they do about the welfare system. His portrait of her is unflinching; so is his portrayal of the demagogues who profited from her story.