“I consider this the ultimate in fan-fiction, basically,” Matthew Lopez says of his play The Inheritance, a two-part, nearly seven-hour gay drama set in New York circa 2016 that came here from London, where it won numerous awards. Considering the whole epic, two-part gay-drama thing, people have been quick to compare it to Angels in America, though the impulse behind The Inheritance really lay in Lopez’s desire to take his favorite novel, Howards End, and “queer it.” Or possibly, given that the author, E. M. Forster, was gay, make it come out of the closet. Lopez updates the 1910 novel, which you may also know from the Oscar-winning 1992 Merchant Ivory movie with Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins, to accommodate a story about three generations of gay men in New York. The class dynamics of Edwardian Londoners who attend Beethoven concerts and vacation in the countryside and care oh so much about real estate have been transformed into the class divisions of gay New Yorkers who spend their time at the Strand and go to Fire Island and, yes, care very much about real estate. (One character unveils a key to Gramercy Park like it’s a holy relic.) Lopez wanted to know, he says, “How faithful can you be to the novel while simultaneously blowing it up?” For those who know Howards End well and need an intro to the gay New York of The Inheritance (or vice versa), the playwright walks a few key lines of comparison between the two.

The Privileged Intellectual

➽ The main character of Forster’s novel, Margaret Schlegel, is an upper-middle-class intellectual who lives in a London townhouse that’s about to be demolished and who likes to get her friends together to debate art and politics. The play’s Eric Glass is a secular Jewish graduate of Fieldston and Yale (“I gave him a great résumé!,” Lopez says) who pays $575 a month for his rent-controlled Upper West Side apartment. “He’s a guy who doesn’t come from wealth per se,” Lopez says, “but he does enjoy a middle-class white privilege.” That’s “so far away from my experience but also a character that everyone who lives in New York City knows and understands.”

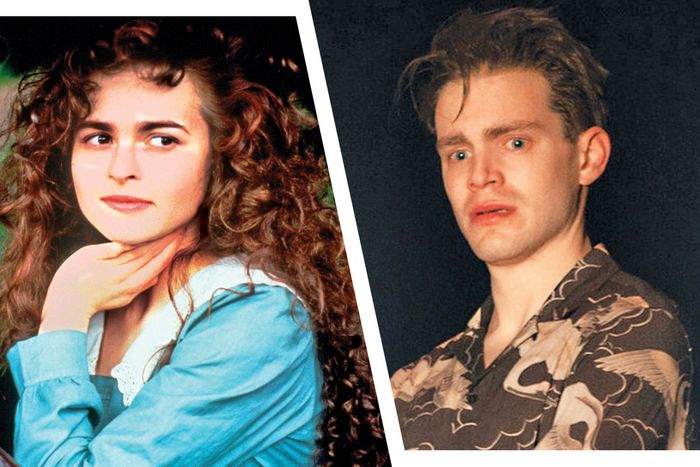

The Cunning, Charming Beauty

➽ Margaret’s younger sister, Helen Schlegel, is flighty, fond of odd causes, and, Lopez believes, the real villain of the novel “because she doesn’t take responsibility for her actions, and her actions are very damaging.” He turned Helen into Eric’s emotional, secretive, very hot playwright boyfriend Toby Darling, a self-destructive addict who resembles a certain type of self-made gay man who can be “caring and thoughtful and charming, and then at the next moment be so cunning and cruel.” Lopez gives Toby the comeuppance he feels Helen needs — ironic, since this is the character he most identifies with in some ways. “It’s fucked up, isn’t it?”

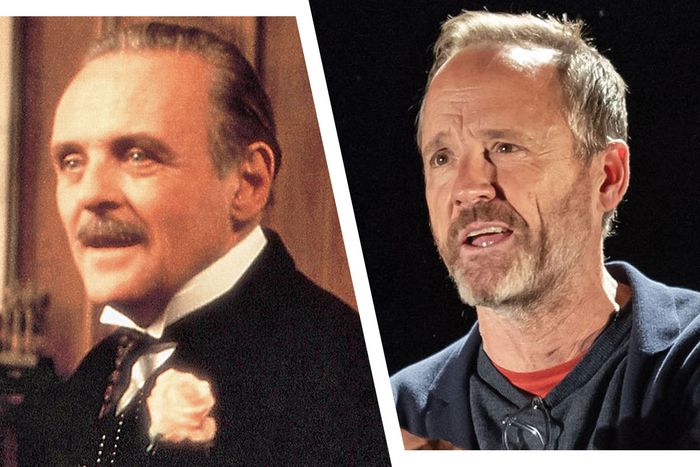

The Conservative Patriarch

➽ The one main character who keeps the same name, Henry Wilcox, British capitalist, becomes Henry Wilcox, American real-estate magnate. Both are superrich members of an older generation who happen to be conservative for their time and who develop a close relationship with the Margaret/Eric character in a way that shocks her/his friends. Lopez likes some of the discomfort that comes across in those scenes: “We yell at each other, we argue with each other, but we’ve forgotten how to talk to each other across differences.”

The Keeper of the Past

➽ A stand-in for the spirit of old England in the novel, Ruth Wilcox is Henry’s wife and the first of the older generation to befriend Margaret. In the play, Ruth becomes Walter Poole, who befriends Eric and speaks directly about his own gay history and memories of the AIDS epidemic. Ruth owns Howards End, a family home that’s key to the novel, while Walter has a home upstate, which is key to the play, as we learn he nursed many dying AIDS patients there. “In figuring out Walter, I figured out the house,” Lopez says. “When I figured out the house, I understood how in writing about generations of gay men I would deal with the epidemic.”

The Working-Class Artist

➽ Completing Forster’s upper-, middle-, and lower-class taxonomy, there’s Leonard Bast, a poor clerk with an artistic sensibility whom Helen keeps trying to save with disastrous results. In The Inheritance, there’s a pair of Leonard-like characters, both played by the same actor, who get entangled with Toby: Adam, a young actor, and Leo, a sex worker. In fact, there’s a bit of Leonard in Toby, too, as we eventually discover. “Maybe why Helen and Leonard get so intertwined and blurred in the play,” Lopez says, “is because I probably have spent my life feeling a little like Leonard Bast and a little like Helen Schlegel.”

That House

➽ Like any good novel about class, Howards End is filled with details about where everyone lives and how well they live. In The Inheritance, we see many of the same details: Howards End itself becomes Walter’s home upstate (originally, Lopez had wanted to set it on Fire Island but decided he wanted a location away from the AIDS epidemic); the modern Henry has a place in the Hamptons; and Eric moves to a place with Gramercy Park access thanks to Henry. New York audiences in particular gasp when they learn about Eric’s low rent: “As they say in the novel, the English don’t really have mythology, only fairies and stuff. New York City mythology is rent control.”

The Great Debates

➽ Margaret spends a lot of Howards End gathering people together to debate the issues of the day. A part when she brings Ruth to lunch with her argumentative friends has now become Eric bringing Walter to brunch (of course) with his argumentative friends. “How do you take that scene with a bunch of Edwardians and turn it into a scene with a bunch of contemporary older millennial and Gen-Z characters?,” Lopez asks. The book’s characters debate women’s suffrage and Teddy Roosevelt, while the play’s ensemble of gay men debates the state of gay culture, Grindr, and even the use of “yass queen.” “That dynamic of generations and classes colliding — that was really interesting to me.”

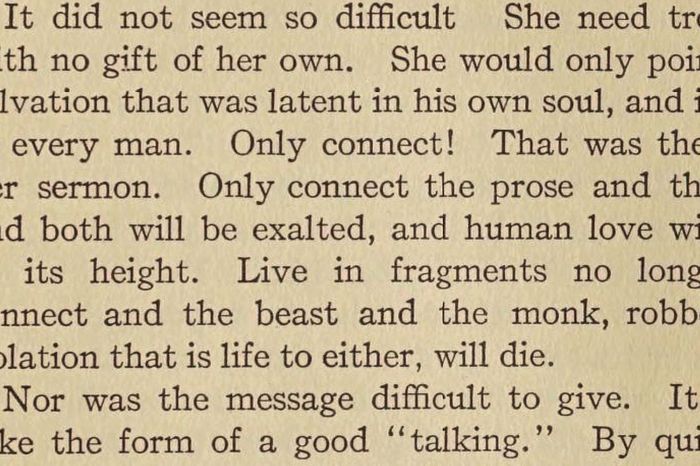

“Only Connect”

➽ If you know one phrase from Howards End, it’s this, which is how Margaret articulates her philosophy. Lopez didn’t get the famous “only connect” speech itself into the play (neither did Merchant Ivory), saying “it felt too on the nose,” but he believes he captured its spirit in a scene when Eric invites friends to Henry’s place and the conversation turns sour over his politics. Given that the scene centers on a debate about a rich, conservative donor, would it today be about boycotting Equinox? “That’s just so boring to me as drama,” he says. “A boycott is literally a refusal to engage. That scene has to be about the willingness to engage.”

The Inheritance is at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre.

*This article appears in the October 28, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!