Four years ago, Shia LaBeouf livestreamed himself watching every movie he’d ever made in reverse chronological order. Well, some of them he dozed through — he’s been working steadily since he was 12 years old, which meant that his full filmography stretched over three days and two nights when screened consecutively. The marathon was in service of the performance art LaBeouf sometimes creates in collaboration with Luke Turner and Nastja Säde Rönkkö — an installation called #AllMyMovies, open to visitors to sit alongside LaBeouf. I managed to slip into the theater early on, before the line stretched around the block, to take in some of David Ayer’s burly tank drama Fury from a few rows behind one of its stars, but it was clear, being there in the room, that I was facing the wrong direction. The point of the piece was to watch LaBeouf watch himself, as he wound his way back from fitful indie darling to volatile leading man to Disney Channel star onscreen.

I kept thinking about #AllMyMovies during Honey Boy, another LaBeouf venture in self-contemplation, and another project that sounds like it should be an act of celebrity indulgence but that instead turns out to be one of startling poignancy. Honey Boy was directed by Alma Har’el in her scripted debut, off an autobiographical script written by LaBeouf while in rehab in 2017. It’s a kind of exorcism of past traumas, with LaBeouf revisiting his days as a child actor from the other side of a key relationship, playing the role of his father against the sweet-faced Noah Jupe as his tween self. #AllMyMovies turned the highs and lows of LaBeouf’s output into a record of his life, a slate of highly selective and sometimes hugely expensive home videos. Honey Boy is the counterpoint, and not just because it serves as a way of putting some of the off-screen parts of LaBeouf’s childhood on the record alongside the work he’d been making at the time. Turning his dad into a character that he can play becomes a way of trying to understand the man from the inside, to get another perspective on what are obviously upsetting memories.

The flashbacks that make up the bulk of Honey Boy take place at the cusp of LaBeouf’s career, when his father (called James Lort onscreen) is serving as his on- and off-set guardian while his mother (Natasha Lyonne, only heard faintly over the phone) works. Otis (the name LaBeouf has given his avatar) is paying James for this service, a point of pain for both of them — James is humiliated by needing the money, and Otis is convinced James wouldn’t be there otherwise. James approaches his caretaking gig with a combination of tough love and neglect, sometimes playing at being the overprotective stage dad and other times leaving his kid to make it to and from a gig himself. The two rattle around a rundown motel complex, making friends and enemies of the other long-term residents (one of whom, played by FKA Twigs, strikes up a blurry relationship with Otis that’s right on the line between maternal and sexual). Harel gives these sequences a dissonant dreaminess, summoning the feeling of nostalgia while depicting incidents about which it’s hard to imagine anyone feeling nostalgic.

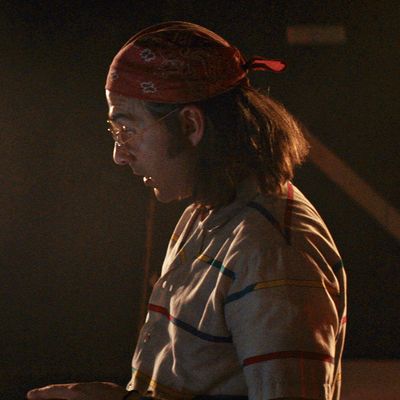

A former rodeo clown, James positions himself as a showbiz mentor and champion for his child, claiming Otis’s mom is undermining him by getting a job as a backup plan: “She’s filling your head full of fear, I pump you up full of strength!” But he’s also a ball of self-loathing and self-defensiveness when it comes to his history as a drug addict four years into recovery, and as a felon on the sex-offenders registry, hyperaware of his own shortcomings but filled with rage whenever they’re pointed out. LaBeouf’s approach to the character is marked by a radical empathy, even when depicting a memory of physical abuse — he portrays his father as someone so consumed by his own pain that he can barely interact with the world around him, much less put his own impulses aside to care for his son the way a parent should.

It’s a remarkable performance, and one that Jupe is impressively able to hold his own against, even when tasked at times to just quietly observe. The pair are so heartbreaking together onscreen that it feels downright disruptive whenever the movie cuts back to its framing device, which features Lucas Hedges playing a 22-year-old Otis serving out a judge-mandated stint in a high-end treatment center after a drunken altercation with the police. Hedges does a pretty good LaBeouf impression, and there’s a nice parallel between the head-on shot of grown Otis dangling in a harness during an action sequence on a blockbuster, and a similar one of young Otis in the same position while getting hit by a pie on the set of his television series. But the scenes of Otis in rehab, getting told by a psychiatrist played by Laura San Giacomo to start writing what will eventually become the movie we’re watching, feel at best unnecessary and at worst like they create distance between the viewer and the raw, real sequences from the past. It’s clear that Honey Boy is an act of therapy, obvious in every intense, effective childhood reenactment. That LaBeouf felt the need to make that literal is a sign that while he has the capacity for great art in him, as a filmmaker, he still has room to grow.