Fame, at least lasting fame — the your-work-goes-down-in-history kind, often accompanied by fat royalty payments — is a club that thinks of itself as an unbiased meritocracy, blind to everything but aesthetic innovation and popular success. It’s never quite worked out that way. When we look at the past, we still see generations of great talents who never quite got their due critically or commercially, many of them left relatively unsung. In this ongoing series, our critics pick artists they feel remain underappreciated and tell their stories and sing their praises.

Success in the music industry is a spurious concept. You can keep a low profile on the charts but stay afloat through ad placements and endorsement deals, as the rapper Vince Staples does creating lean, anthemic music that kills in clubs, movie trailers, and Sprite commercials. You can have an inescapable presence on TV and radio and still be functionally penniless, as the R&B singing group TLC revealed at the 1996 Grammys, where they won two awards for the multiplatinum 1994 album CrazySexyCool, then shocked journalists by announcing that they were “broke as broke can be” at a postshow presser. The British singer Clare Torry knows the biz’s peaks and valleys; a life-changing evening phone call once landed her an indelible appearance on an album that would go on to sell over 45 million copies worldwide and create a lasting legacy as one of the finest moments in rock-and-roll history, but she was paid a day laborer’s wages for her contributions and she had to fight just to get her name on the finished product.

The album is Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon. The song is “The Great Gig in the Sky,” the volcanic interlude that famously nudges the druggy, oceanic lilt of the single “Time” into an orgiastic frenzy. Torry’s performance manages to express the full range of human emotion without relying on words. She whoops and wails through octaves before collapsing into her lower register and trailing off into silence as the drums drop out and pianist Richard Wright and bassist Roger Waters pluck out a coda that sounds like an elegy. Dark Side producer Alan Parsons discovered Torry doing covers for Top of the Pops, a long-running compilation series that successfully sold convincing facsimiles of the hits of the day recorded by uncredited session musicians. Featuring Torry netted the band a timeless performance — the song is pea soup without her — but at the end of the night, she was paid just £30, and that much only because “it was double time on a Sunday,” as she’d later tell John Harris, author of The Dark Side of the Moon: The Making of the Pink Floyd Masterpiece.

Session work is rewarding but also nomadic and sometimes frustratingly anonymous. Great players participate in memorable work but shuffle along to the next before the accolades roll in. Their names are known only to bands, industry hawks, and intrepid diehards who comb album credits (insofar as these names ever make it into the credits). You can probably conjure the fleet disco beat of Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” from memory, but the name of the player — Leon “Ndugu” Chancler, who was versatile enough to drum for everyone from Miles Davis to Lionel Richie — isn’t common knowledge. Torry’s singing career never quite reached the altitudes to which her elastic range and white-hot passion seemed destined. She started gigging on a lark to settle an overdraft fee with her bank in the late ’60s but stuck around because it felt natural. Early singles like “The Music Attracts Me” and “Unsure Feelings” bricked despite Torry’s lovelorn delivery, a mix of simmering intensity and complete control not unlike that of the American blue-eyed-soul singers Todd Rundgren and Laura Nyro, but companies like the U.K. airline British Caledonian tapped Torry for adverts.

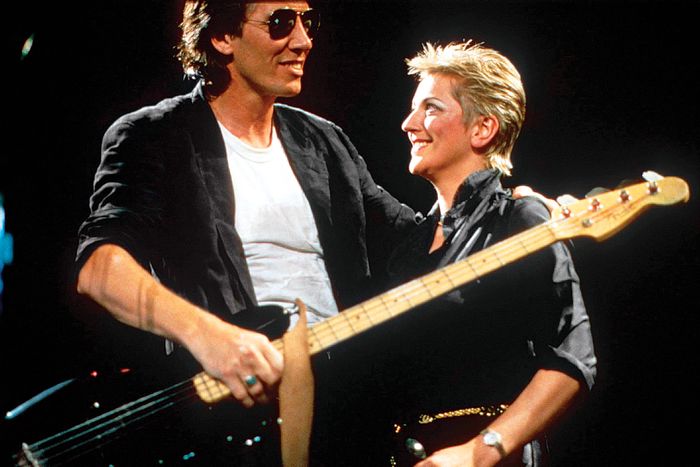

The singer was never at a loss for work behind the scenes, but her push for solo stardom was met with relative indifference. Prime real estate in the middle of The Dark Side of the Moon didn’t change Torry’s luck as a solo artist, but the Pink Floyd connection did make her voice a respectable commodity to an eclectic lot of musicians. Her late-’70s oeuvre includes appearances on the French disco composer Cerrone’s “Angelina,” the Alan Parsons Project’s “Don’t Hold Back,” and albums by the singers Olivia Newton-John and Serge Gainsbourg. In the ’80s, Torry guested on Waters’s Radio K.A.O.S. and Tangerine Dream’s “Yellowstone Park” and had an international hit with Culture Club’s “The War Song,” on which she replicated her famous wordless wail in the middle of Boy George’s peace anthem.

Torry didn’t get her moment in the spotlight until she retired and finally listened to friends who were urging her to pursue further compensation for her finest hour. She sued Pink Floyd and its label, EMI, in summer 2004 for songwriting credits and lost wages for her work on “The Great Gig in the Sky.” The case was settled out of court in 2005, and further anniversary pressings of The Dark Side of the Moon have included Torry’s name as a co-writer on the track. In 2006, a collection of Torry’s early solo work was released; Heaven in the Sky is a glimpse at what should’ve been a successful solo career. “Theme From Film ‘OCE’ ” pulls the “Great Gig” vocal trick over a country shuffle that resembles Rundgren’s “The Night the Carousel Burned Down.” “Love for Sale” and “Heaven in the Sky” prove Torry can light up an electronic composition as confidently as she does a syrupy big-band romp.

The 1973 single “Carry on Singing My Song” is an unwitting mission statement for the rest of Torry’s career. It’s about picking up the pieces after a moment of misfortune. “Do you cancel the rest of your life?,” the singer muses in the first verse, then the chorus blasts in on a fanfare of horns and strings, and Torry’s mournful mood starts to soar. “I’ll just carry on singing my song,” she shouts, “carry on making my own kind of music.” The original lyric’s about a breakup, but it’s hard not to see the rest of her career through the lens of the line. Torry has lived out her words in the 47 years since the fateful winter-Sunday studio session that landed her within arm’s length of stardom. She honored her gift and burrowed her way into the company of rock and pop royalty even when support for her solo work flagged, then she finally saw her payday in retirement with ample time to sit back and enjoy it. That’s an ending as neat as a fairy tale’s.

*This article appears in the January 6, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From 'The Undersung'

- Anne Beatts Was Always More Interesting Than John Hughes

- What We Lost When Euzhan Palcy Left Hollywood

- Euzhan Palcy Remembers the Fight to Make A Dry White Season in Hollywood

- The Best New Novel Was Written 90 Years Ago

- Gillian Armstrong and Her Protagonists Redefined the Modern Movie Heroine

- Alice Childress Didn’t Defang Her Plays, and Producers Said No