Every protagonist in literature is lonely. Jane Eyre, Elizabeth Bennet, Pip, Miss Jean Brodie, Holden Caulfield. They all live inside themselves — that’s what makes them interesting. The contented character has no place to go, no paths to improvement or destruction or unravelling.

But there’s a certain kind of isolation that makes for a vivid reading experience — when the protagonist is quite literally all alone, whether by circumstance or choice, either struggling to be seen or hoping to disappear even further. The novel, after all, is the perfect medium for that message, the only art form in which an interior monologue doesn’t regularly come off as hokey. If you’re into that kind of thing, and want to grapple a little harder with the bizarre swaddling effect that COVID-19 has had on our ability to simply stand close to another human, here are nine books that offer insights into the wild terrain of the isolated mind.

Yambo has suffered a head injury. He can remember every book he’s ever read, every cartoon his childhood self rapturously took in. But he doesn’t recall a thing about himself — not his marriage, not his childhood, not his current life as a bookseller. So he immerses himself alone in his attic collection of his life’s paraphernalia, digging through the cartoons and scraps of paper that he thinks might define who he is. Eco’s underestimated fifth novel is a riot — you’ll find more than a small bit of joy in here — and a vivid meditation on the things we can learn about ourselves when we’re stuck inside with all the detritus of our past.

As spare as the sunbaked Greek island it’s set on, Katie Kitamura’s A Separation plucks its unnamed protagonist out of her life as a translator in England and rockets her off to find her missing husband who, as the title suggests, had recently walked out of their marriage. The woman can’t get any solid information out of hotel staff or locals — nobody seems to want to explain where her husband might have gone. And as she searches alone, the island itself turns menacing, with warnings about drowning on the coast and the purposely set fires inland. Like Muriel Spark, Kitamura knows how to endow even the smallest moments — a conversation witnessed through glass — with menace.

Hear me out. Yes, this is a novel narrated by a baby floating “upside down in a woman.” Yes, it’s also a retelling of Hamlet set in modern England. Yes, it’s written by Ian McEwan, who either knocks it out of the park (Saturday) or doesn’t even bother to swing (Enduring Love). It’s also the most innovative investigation of what it means to be helpless and alone that I can recall reading. “There’s hardly enough of me to form one small animal,” he thinks, “still less to express a man.” This fetus is wise and oratorical, overhearing his mother and her brother-in-law’s plot to kill his father and take over his coveted £8 million home in central London, and then plotting his own ruse to keep his father alive with the few tools at his disposal. Weird and wonderful.

Jake Whyte is tending her flock of sheep on a remote, rain-blasted English island. Something — whether man, fox, or wolf, we don’t know for sure — is hunting those sheep and mutilating them one by one. If this sounds like the premise of a thriller, well, it is, but not of the usual variety. Jake lives inside a soundstage of her own mysterious past, and as she turns huntress herself — setting up at night with her gun and a whiskey— this menacing novel asks how we can stay safe from outside dangers if our insides have gone to rot.

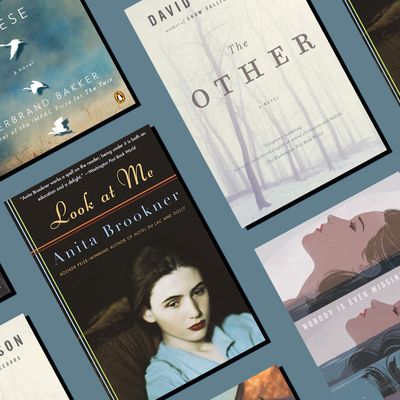

Brookner has a niche — lonesome but sensible middle-class lady is left to her own devices (often abandoned by her mate) and lapses into a self-created mind maze. Look at Me is the standout of that mini-genre, the singular Book of the Desperate. Frances “I do not like to be called Fanny” Perkins is an aspiring novelist who works at a medical library, where she spends much of her time observing the patrons, especially the graceful and confident Dr. Nick Fraser, “a model of how ideal a man might be.” When she’s taken under the wings of Nick and his vivacious girlfriend Alix, Frances senses “high hopes for a future that would cancel out the past.” But in this ultimate third-wheel novel, Frances can’t properly wedge herself into their twosome, and the title ends up both a demand and a lament: Look at me.

In 2013, authorities discovered a man named Christopher Knight, a.k.a. the North Pond Hermit, living in the woods near a Maine lake; he’d been there, in an artfully constructed tent, stealing campers’ supplies, for 27 years. David Guterson’s 2008 novel precedes that story, but the similarities are abundant — in The Other, trust-fund baby and restless scholar John William Barry moves into a limestone cave in a Washington forest with only a few supplies, and then refuses to emerge. Why? “I don’t want to participate.” Told from the point of view of John William’s (only) dear friend, family man Neil Countryman, The Other is the story of both men and their bizarre entwinement, but it’s mostly a question about what it means to step so far off the grid that you become lost inside the raw animality of life.

An Emily Dickinson scholar sets up home on a farm in rural Wales, fleeing her marriage. But she’s also stepping toward something —her intimacy with the poet and a new understanding of a woman who resigned herself to her father’s house and grounds for two decades. Dickinson, she believes, managed “to hold back time, making it bearable and less lonely too perhaps, by capturing it in hundreds of poems.” As she plots the land around her crumbling little house and slowly watches a flock of creamy geese disappear, the scholar immerses herself in the difficult work of taking up residence entirely inside herself. Bakker, famous in his native Netherlands, is still relatively unknown in the U.S., but this novel ought to have made a literary legend out of him.

Not many novels can claim that large swaths of their plots take place in a well, except Murakami, who sends his protagonists tunneling under the earth at the slightest sign of reflection. In this massive, seminal work — too lengthy and tentacled to explain in all its heavily plotted glory — Toru Okada goes searching for his cat and his wife, both missing, and finds himself encountering mysterious strangers, almost all of whom besiege him as he struggles to move on without knowing where his spouse may be. But the most moving bits are his time alone, gazing in the mirror at a strange blue mark that has bloomed on his cheek, wondering which parts of his lonely existence are dream, and which are real.

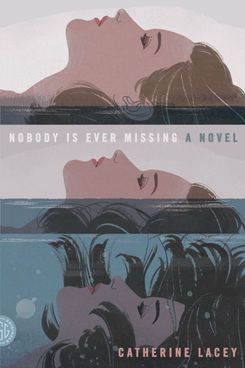

One day Elyria walks out of her life in New York, steps on a plane to New Zealand, and simply begins wandering, alone. Sure, there are practical details to explain why she might leave her husband without as much as a note, but in this dreamy, compact novel, we’re simply bystanders in her whirring brain. Elyria moves from a bush to sleep in to a beach to huddle on, occasionally zipping backwards in time, but mostly contemplating a life lived outside of linear time and three-dimensional space. Lacey, one of her generation’s most exceptional talents, doesn’t glamorize a wayward life, but instead questions if it’s possible to step outside our own lives.

Every editorial product is independently selected. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.