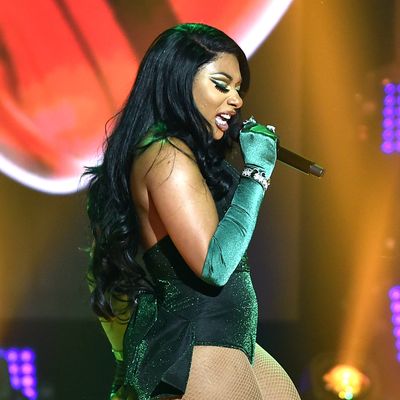

In a week, the ongoing contract dispute between Houston rapper Megan Thee Stallion and 1501 Certified Entertainment, the Texas indie record label that signed her in 2018, has rapidly devolved into one of the most lurid rap-label tiffs in recent memory. On Sunday, Megan told fans that 1501 was attempting to block the release of her new album Suga, because she signed a contract without fully understanding its verbiage and requested a renegotiation, only to have 1501 put her on lockdown. On Monday, the rapper sued to have her contract tossed out on the grounds that the deal, signed when she was 20 years old, gave 1501 a cut of the money she makes from records, tours, merchandise, and endorsements that is disproportionate to the services the team has been able to provide. On Tuesday, 1501 owner and former MLB player Carl Crawford told Billboard he doesn’t handle the day-to-day at his label and blamed Swishahouse president of A&R, T. Farris, and Megan’s mother, Holly Thomas, who died a year ago this month, for the terms of the rapper’s contract. On Wednesday, a judge barred 1501 from interfering with the release of Suga, which is out now — two months ahead of the originally scheduled May release date — and with nine tracks in 24 minutes, ostensibly much smaller than intended. “When you got a window, you gotta take it,” Meg told Vanity Fair yesterday.

This war over splits and ownership of masters, accusations of threats from associates, and complaints of disloyalty from signees brings into sharp relief the inherent difficulties of getting a career in mainstream hip-hop off the ground. It’s a costly endeavor, navigating a field rife with shrewd businessmen and outright scammers. You don’t find out which is which until some money comes up short. The overwhelming early response to Meg’s story, and to Crawford’s rebuttal, has been that young artists should expect to have a label drive a hard bargain until they reach a tipping point where the artist can apply pressure and renegotiate. The logic doesn’t take into account the fact that you can be at the peak of your cultural reach and still feel like you’re getting jerked in your contract. The capitalist bedtime story that tells us there’s a point when our toil is rewarded with equity flies in the face of the stories of Drake, Kanye West, Taylor Swift, Lil Wayne, and Lil Uzi Vert, artists with platinum singles and No. 1 albums who have all accused their labels of stifling their creativity or else resorting to nefarious business practices at various points over the last few years. The machine is vampiric. The idea that we all must suffer to get ahead is a grisly American pathology making people do spooky shit like bristle at the possibility of waiving student loans. The idea that it’s too soon for Megan Thee Stallion to want a more fair deal is a fault in our own thinking, not hers.

But what of Suga? Does it make 1501 look like they blocked their blessing? Is it worth the fight, or was it kneecapped by the rush to get product out while Meg has a court-ordered green light to drop new music? The answer is a bit of both. The record (EP? Album? Mixtape? “Project”?) is front-loaded with sex-positive bangers that tap into the same vein of Megan highlights like “Hot Girl” and “Big Ole Freak,” off her 2018 Tina Snow EP (?). “Ain’t Equal” kicks off with a state of the union address, as Meg maps out the wins and losses of the last year and talks a grip of trash about anyone still standing in her way. Its second verse ends with the most concise put-down in the war of words between the artist and her label — “And since the nigga think he made me, tell him do it again” — serving a sharp reminder that she’s the jewel of the 1501 roster (while nodding to the time her Roc Nation boss Jay-Z got mad at old business partners and rapped, “I heard motherfuckers saying they made Hov / Made Hov say, Okay, so make another Hov”). “Savage” is joyfully conceited; “Captain Hook” houses killer flows and one of the best dick jokes of the young year.

Midway through, Suga changes pace, opening up for breezier, R&B-infused tunes designed to show off Megan’s range and allow her to step outside the rough-and-tumble war-ready raps she’s known for. The Kehlani collaboration “Hit My Phone” and the lead single “B.I.T.C.H.” are G-funk throwbacks that look good on Megan, who was raised on ’90s rap classics. The latter is an answer record for Tupac’s All Eyez on Me deep cut “Rather Be Ya Nigga,” an audacious move in an era where older rap fans rattle sabers every time someone 25 and under offers an opinion on B.I.G. or Pac. Both songs float, but “B.I.T.C.H.” is a little lightweight as a first single when there’s heat like “Savage” on deck. Wade deeper into Suga, and it’s apparent that Megan aspires to more than just spitfire bars and ice-cold threats. The last three songs all boast beats from veteran rap producers Timbaland and the Neptunes, and singing where you might expect rapping. On “Crying in My Car,” it’s license to get more vulnerable (although the Auto-Tune coating hits weirdly), but on “Stop Playing” and “What I Need,” the vocals and melodies leave much to be desired.

Ending the project weaker than it started makes Suga feel like a half-step toward the evolution Megan had planned when it was being touted as a proper album. Short projects need to be all killer, no filler, and there’s around two or three skips out of nine here. Releasing a project that doesn’t quite sustain the quality of Tina Snow and last year’s Fever when the audience could’ve lived with a trickle of singles invites the question of whether Megan Thee Stallion is saving fire for a better legal situation or just striking while the iron is hot. As it is, Suga is a solid batch with a few too many seeds and stems, an EP’s worth of fun where a louder, stronger statement was required.