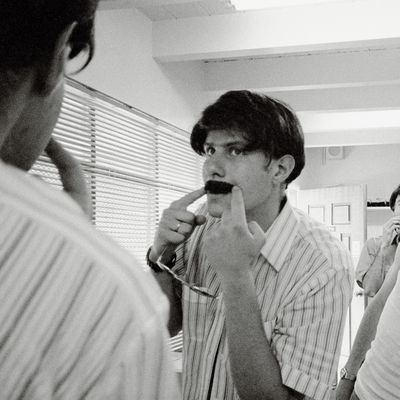

It was Adam Yauch — back when he (MCA), Mike Diamond (Mike D), and Adam Horovitz (Ad-Rock) were just kids kicking around New York City in the early ’80s — who wanted to start a group called the Beastie Boys. And when Yauch died of cancer eight years ago, Diamond says at the start of the new documentary Beastie Boys Story, “we stopped being a band.” He and Horovitz instead offer themselves up onstage as two-thirds of a whole, a pair of middle-aged artists looking back over the musical collaboration, and the friendship, that encompassed over half their lives, a constant over ups and downs in a way that’s unusual in the business. Accordingly, Beastie Boys Story isn’t a document of a musical performance, but of the recounting of a musical history, shot over three nights at the Kings Theatre in Brooklyn last year. It falls somewhere between an elegy and a victory lap, the remaining Beasties sharing memories and trading quips over photos and archival footage, with occasional breaks to queue up one of their hits.

It can be hard to assess something like Beastie Boys Story as a stand-alone work when it’s so forthrightly intended for fans — the equivalent of a DVD extra for a whole career, a movie that assumes it has your implicit buy-in if you’ve even opted to watch. The doc is the end result of a set of projects that started with a sprawling 2018 book written by Diamond, Horovitz, and a slew of contributors who were friends of the group, famous, or both. That spawned an audiobook version read by a chorus of celebrity voices, leading to a live performance that streamlined those stories into something that could fit into an evening. But the resulting film is disconcertingly square — especially coming from a group that once turned the shooting of a concert doc over to the audience, and especially considering it’s technically the first feature since 2013’s Her from longtime Beasties collaborator Spike Jonze.

The camera scurries up the aisle at the start of the live show (which was also directed by Jonze), makes a retreat into the wing at one point alongside a prop, and turns around during a flub to survey unruly teleprompters that have jumped ahead of the proceedings. Otherwise, it remains pragmatically trained on the stage, where Diamond and Horovitz, standing in front of giant slides in sensible khakis under bright lighting, can look a little like they’re delivering a TED Talk. Not, again, that it will matter to devotees. It doesn’t appear to matter to the ones in the audience, who applaud enthusiastically at every mention of a beloved track or a treasured influence. Like the musicians they’ve come to see (and the person writing this review), they’re mostly at an age at which assigned seating is a venue must, and they appear as eager for a trip down memory lane as their genial hosts.

It’s hard to begrudge the men this chance to revisit their raucous past, from the Beastie Boys’ formation in the punk scene to their final gig at Bonnaroo in 2009 — not when the proceedings are framed as much as a tribute to Yauch as to the band, continually touching on his contributions and his absence until he emerges as the guiding force for the trio’s personal and artistic growth. “‘What would Yauch do’ is always on our minds,” Horovitz reflects before he and Diamond launch into an account of how the trio almost lost themselves early on, when the line between joking about party bros and being them became blurry, and then nonexistent. Beastie Boys Story isn’t all golden nostalgia, delving into some mistakes and regrets — particularly in those heady days around 1986’s Licensed to Ill, when the group rocketed toward fame and notoriety. Diamond and Horovitz focus in particular on how they kicked out Kate Schellenbach, the group’s original drummer, after falling in first with a young Rick Rubin, and then with Russell Simmons.

The willingness to go warts-and-all is nice. But in treating the history of the Beastie Boys’ as a condensed bildungsroman that takes the trio from obnoxious little shits to more enlightened adults, the documentary can veer toward self-serving. Stories about cussing out audiences when serving as Madonna’s unlikely opening act and arranging for a giant dick to be part of the stage setup on their first big tour are put forward as amusing examples of youthful idiocy — which they are! But presenting Simmons, for instance, as a villain mainly in the context of how he screwed the band on royalties feels like a noticeable omission, given the barrage of allegations made against him in the years since. In the rush to make assurances about the group’s later feminist awakening and amends-making (citing Yauch’s lyrics that “I want to say a little something that’s long overdue / The disrespect to women has got to be through”), there’s little acknowledgment given to the widespread industry misogyny they acceded to in order to chase that first big break. The lens never widens beyond their personal growth.

Schellenbach, in particular, ends up feeling reduced to a narrative accessory. First she’s a casualty of the band’s original deal with the devil that is the music business, and then an unknowing conscience that Horovitz is too embarrassed to acknowledge when back in New York. Later, the fact that the Beastie Boys’ record label signs Luscious Jackson, the band she’s joined, becomes an indicator of maturation and reconciliation. There isn’t really room for more in Beastie Boys Story, structured as it is around twin narrators, and already feeling overlong even when trimmed down from a lengthier live event. And that might make you wonder what the benefit of this format is, aside from providing a chance to repackage these stories. They’re stories you can find in the book, accompanied by ones from a multitude of other contributors, including Schellenbach, who gets to give her own account of what happened. So why not just read that?

More Movie Reviews

- Death of a Unicorn Is 5 Pounds of Purple Poop In a 10-Pound Bag

- The Thriller Drop Is a Perfect Addition to the Bad-First-Date Canon

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously