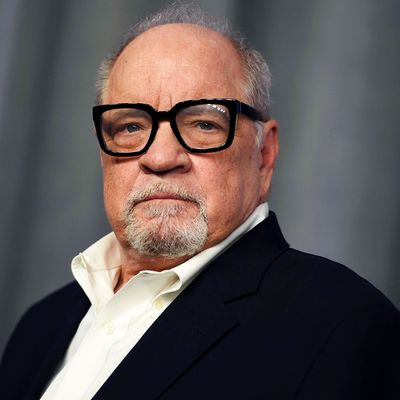

Back in March, Paul Schrader caused a bit of a stir when he wrote a Facebook post condemning the producers who stopped production on his film The Card Counter (starring Oscar Isaac, Tye Sheridan, Willem Dafoe, and Tiffany Haddish). It was day 15 on a 20-day shoot when a “day player” on the set was diagnosed with the coronavirus. “Myself, I would have shot through hellfire rain to complete the film,” he claimed. “I’m old and asthmatic — what better way to die than on the job?” This wasn’t the first time the filmmaker roused indignation on social media. After writing last year that he’d have no problem casting Kevin Spacey if Spacey were right for a part, Schrader’s First Reformed distributor forbade him from posting anything between his Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay and the awards ceremony. After the Oscars, he jumped right back into the pit. Not that he perceives himself as a provocateur. It’s just that his instinct to say what others won’t (sometimes for good reason!) has gotten him where he is, and passionate responses — pro and con — embolden him.

The Schrader I’ve known for years is a deeply moral man with a deeper dislike of hypocrisy. Since his famously Calvinist midwestern childhood, he has ventured — creatively, anyway — into the darkest areas of the psyche. When Taxi Driver (for which he wrote the script) won the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the audience reacted with boos, and even today the movie spurs angry disagreements. (It was a partial inspiration for the controversial Joker, which Schrader will not publicly discuss.) As a director, his films — among them Blue Collar, American Gigolo, Cat People, Light Sleeper, Auto Focus, The Canyons, and last year’s stunning First Reformed — differ hugely in setting but are thematically of a piece: People keep things in for various reasons and then suddenly don’t.

I’m grateful that Schrader was willing to share his thoughts and feelings by phone, from his house north of New York City. The following interview — taken from two separate conversations — was edited for length and clarity.

Are you working on your film right now?

It’s Saturday, but yesterday I was.

How does that feel?

Well, it’s my third film with this editor. So we know the rules.

But you’ve always been in the same room before …

We see each other and we see the screen, and eventually we’ll be in the room together. We’re working on several things. One is a standard work-in-progress. Another is a product reel, because they’re talking about having a virtual Cannes where you can sell your product reels. And the third thing: I’m working on what would have been if I had lived.

What the hell does that mean?

Well, I’ve done all the big dialogue scenes. I have a number I haven’t done — a number of prison scenes, and I can mock those up by using Google Images and getting Oscar [Isaac]’s voice to say dialogue. And I can sort of show what the film would have been if I hadn’t died before finishing it.

So that’s your worst-case scenario. [Editor’s Note: Schrader has tested negative for COVID-19.]

Yeah, but also it’s a part of finishing the film. Essentially, it’s a form of previs. You know what previs is?

I don’t.

Previs is an animated storyboard. The way they can make all of these high-tech movies now is they previs them. They shoot them, and edit them, and reedit them all in advance of production and then shoot them with actors against green screens and have the previs animations running simultaneously. The director is watching the previs animation and seeing the actor in the real environment, even though the actor’s not in the environment.

But what percentage of your shooting is finished?

About 80 percent. So all of the big stuff is actually done, and I wanted to muscle through [in March], but it would have been unethical.

You would have still done it, though …

I was ready to do it. I was ready to work right over the weekend. But we were in casinos in Biloxi [in Mississippi], and the casinos closed down Tuesday and we shut down on Friday. So even if I had decided to muscle through, I wouldn’t have been able to.

You had the momentum and you just thought, you know, We’ll get through this? Nobody was sick?

We had a scene with 500 extras, and one of them reported back that he was positive. At that point, you have all kinds of legal implications. If you keep shooting and hide the fact and then it comes out, that’s a hell of a liability.

That’s a hell of a moral responsibility, too.

Yeah, well, I was more worried about the legal liability than the moral one.

That’s gonna sound very callous.

I just had a long conversation with Michael Mann. I knew that Michael was shooting a TV series in Tokyo, Tokyo Underworld. He had to shut down, and he was totally opposed, and he was in the same situation I was, which is you can keep shooting but you’re going to be the only one on-set. So he had to come home, too. But, you know, that’s the way it is with film directors. They’re all alpha types.

You’re the general who wants to send people into battle, no matter what the odds?

No, you’re the general who wants to lead people into battle!

Because you would have been out in the front?

Absolutely. You say, “If I’m willing to die for this, you should be too.” That doesn’t sound as good to others as you’d think it might. So I drove back from Biloxi, and I’ve been out of human contact.

Who’s in the house with you?

My daughter just came up from the city. And I have a dog who is the most loved animal on earth. But I’m doing this thing where I’m calling people I haven’t spoken to in a long time. They are so happy. I called up Pat Resnick. She wrote 9 to 5. I called up Paul Jasmin, who’s a kind of a Bruce Weber–like photographer who did the ad campaign for American Gigolo. I called up other people I’ve worked with over the years, and they’re all so appreciative. They say, “I never thought I would hear from you again.” This is the greatest excuse in the world to talk to people who you used to know. You just call them up, and you say “How are you doing?,” and they immediately understand why you called.

We can all be lonely together.

I knew Michael Mann quite well about 35 years ago. I called him up, and the first thing I said was, “[It’s] Paul Schrader. How are you doing?” And he immediately responded, “Oh, thank you for calling!” Whereas in another time, Michael would say, “What do you want?”

You have quite a cast in The Card Counter. What’s it about?

It’s another one of those Schrader movies.

Meaning Oscar Isaac is God’s loneliest man?

He’s the guy in the room, wearing a mask, waiting for something to happen, and the mask is his occupation. In this case, it’s a professional poker player.

You’ve never done a gambler movie, have you?

Yeah, and this isn’t one either. I don’t give a damn about gambling. I don’t give a damn about boxing. I don’t give a damn about taxi driving. These are all just metaphors. What I try to [do] is if there is a problem that’s bothering me, then I try to find two concurrent metaphors. One metaphor may in fact be the problem. So the problem is loneliness, and the metaphor is the taxi cab. The problem is loss of faith, and the metaphor is climate collapse. The problem is midlife crisis, and the metaphor is a drug dealer. I find these two sorts of things that are sort of alike but not alike at all and run them alongside each other until sparks start jumping. So the two things on this one — I was worried about the problem of punishment. If you are truly guilty, is there any end to punishment? Can you ever be punished enough? This is a nice Calvinist problem, and we know the answer to it.

What is his sin?

That’s when it gets interesting. I was looking at the World Series of Poker. I said, There is a blankness there. That is the blankest world. They’re just sitting there ten, 12 hours a day, running numbers through their heads just like slot players are. It’s a way to not exist and pretend you are existing. So what kind of person would choose that kind of occupation to not exist if he was under guilt? Then I said, Of course. There’s only one guilt sufficient in our times. It’s Abu Ghraib. My guy was one of the torturers. And not only one of them, he loved it. He was enjoying it, and he went to jail for eight years.

Did any of those guys go to jail [in real life]?

Yeah, five of them did. Only the ones in the pictures. Nobody who wasn’t photographed went to jail.

Lynndie England — did she go to jail?

Yep, and Charles Graner went for six and a half years. But none of the guys who instructed them. None of the guys who paid them served a day. So that’s my guy. He goes from casino to casino following conventions. He likes police conventions because cops are bad gamblers — they all think they know better. He’s just waiting for something to happen. Just like in Taxi Driver, days go by — every day like the last day — and then something happens that will define his nothingness. He’s at a police convention in Atlantic City, and he wanders into this lecture hall, and Willem Dafoe is giving a lecture on new advancements in facial recognition and lie detection — to take [interrogation] to the next level. He’s feeling more and more uncomfortable as he’s listening to this. And there’s a young kid, Tye Sheridan, who’s looking at him across the room. Finally, he can’t stand it anymore, and he gets up and leaves and the kid follows him outside. He says, “Do you recognize him [the lecturer]?” And Oscar [lies], “No.” Tye says, “Well, here’s my name. I’m staying at this hotel. If you want to call me, call me.” He goes to his motel room that night, and he has a dream of Abu Ghraib, of what he went through. He gets up at 3 a.m., calls the kid up, says, “Okay. Come on down. What’s your story?” [It turns out] the kid’s father was also a torturer and was taught by that guy — who’s insane but still out there making money.

Like those real torture instructors who were in the movie The Report?

Yeah. Originally, I called him Hernandez. Then Oscar’s wife said, “Why do the torturers have to be Hispanic?” Because he is! His name is Jose Rodriguez. But I changed it. Anyway, the kid says, “The same guys who taught you taught my father. My father was at Bagram. You were at Abu Ghraib. My father came home. He had an Oxycontin problem. He beat my mother a lot and then she fled without telling anybody in the middle of the night. Then he started beating me and then he shot himself.”

[Here, Schrader tells me the entire story of the film, which should not be divulged. I will say that the kid wants vengeance on Dafoe’s torturer, and Isaac’s character discourages him — to the point where he fixates on helping the younger man restart his life. What all this builds up to is like nothing else. It makes the bloody climax of First Reformed look Disneyesque.]

Did you spend a long time studying torture techniques?

There’s not a lot to learn.

There’s not?

I mean, any 12-year-old can tell you how to do it. Anybody who’s ever tortured a frog or dog, as we all did in the Midwest, knows how to do these things. This guy Jose Rodriguez devised all these modern rules which were adaptations of old rules, such as water torture. They brought him from Nicaragua over to Guantanamo, where he then perfected those techniques. Then they brought him to Abu Ghraib and Bagram and to all the various dark sites, where he instructed people on what he had learned about what works.

So you lived with this stuff for the last year?

Well … You know … I mean, it’s another job. It’s just a job; it’s a mask. I was never a gigolo. I was never a minister. I was never a drug dealer. I was never a torturer.

You haven’t done a revenge scenario for quite a while.

Yes, but it’s a man who is fighting against revenge with all his might and then this boy comes into his life, just like a boy comes into [First Reformed’s] Reverend Toller’s life and drives him into a course of suicidal purification. So, David, why did you call me again?

Well, I wanted to find out what it has been like having a film stopped and then living with all that footage.

The same terrible thing happened to every single production and everybody who was interested in them then is now very, very interested in which of them can put up a product reel that is sellable. But no one even knows if there will be a fall season. There are a couple scenarios out there, and one is a recurrence [of the virus] in early fall, in which case there would be no fall season. Everyone’s scrambling for models. Because I have a film with some cachet, both in terms of actors and my name, I have buyers who are interested. They’re not making offers, but they want to see it. Whatever I have — 30 minutes, 45 minutes, an hour. That’s one of the things we’re doing.

You’re in better shape than many indie directors with half-completed projects I know.

Yeah. I have footage. I have well-known actors. I have stills. I had [the head of a major film festival] calling me about it. People in that other situation are truly and deeply fucked. Because they were flying on a wing and a prayer and then they crashed and don’t know whether they’ll ever get afloat again. All those low-budget films that rely on festivals for any sort of credibility. We think of the top ten [festivals], but there’s another 50 or 60, and all you have to do is be a hit at one of them, and then another festival will pick you up, and then another festival will pick you up, and then you can possibly make a sale. That is the only road to financial viability for these films. The other road is you sell to Netflix for $100,000. And basically that means everybody loses money.

And it’s seen.

Yeah, but it also disappears. It falls into the great nether blackness of Netflix. I’m gonna survive this quite well. I have no question about it, but boy are other people gonna get hit. If Berlin [International Film Festival] happens [in 2021], every single important film will want to be there. Every film that refused to go to Berlin in the past is gonna want to be there.

You’re assuming that Toronto and Venice won’t happen?

I think they’re iffy. I think Berlin’s probably the first major festival. God knows I’d love to be in Telluride this fall.

Maybe Sundance in January?

Sundance and Berlin are the next window, but Berlin is where to premiere big-ticket international films.

Who knows if other filmmakers will even get their movies finished in time? What if the actors are suddenly very in demand as soon as the machine starts up again?

Depends how deeply committed your actors are. I have actors who I’m speaking to and I’m calling who are brokenhearted and saying, “I’m here for you — any time, any day, any week, any year.” Here’s the thing that’s gonna be the most interesting: how theatrical will hobble back to life. Is there any way theatrical can reposition itself as an important force?

What do you think?

I think it was hanging on by its fingernails, and somebody just chopped those fingernails off, and it will reemerge in a specialized way, in the same way that blues clubs and symphonies emerge. But it will never ever assume the profile it once had.

What about the multiplex spectacle?

I assume that would live. But I think that may even be in danger now. The one that is most failureproof is the children’s movies, because every parent wants to see their children having fun with other children. So if anything can come back, it will be children’s cinema. That’s assuming that these corporations like AMC can survive their debt burden. If they’re down for eight months, at what point do they simply sell their real estate? Nobody can say, “Hey, movies are such a hot business, and we’re gonna be cooking.” Everybody gives you that long eye. We know Disneyland is gonna come back, but we don’t know if movies are gonna come back. I assume you’re watching a lot of movies at home.

I have no choice, yes.

My daughter is living with me up here in the country, and every single night we watch a classic movie.

I envy you.

And these are all the movies that informed me. We watched Red Desert, Masculin Féminin, The Conformist, Performance, Tokyo Story, The Makioka Sisters … She would never watch these films otherwise.

I can’t get my daughters to watch those movies with me.

You gotta pick the right movies, and you have to say, “Your father would not have been who he is if he hadn’t seen this movie.”

In my case, it would be Taxi Driver, and I’m not sure what that would tell them.

For a young person, Masculin Féminin is amazingly accessible. So is Persona. I showed that to my daughter, and she was stunned just by the feminine politics and the visual genius of it. So, you can walk your children through a film education they wouldn’t have had unless they were isolated and incarcerated.

That might be the one silver lining in all of this. But I worry that culture is getting more and more and more private. I don’t think our senses are as heightened at home as they are when we see things in public. We have too much control.

But what we’re looking at now is a reconfiguration of how we perceive audiovisual entertainment, and I don’t think we will ever go back to where we were six months ago. I have this whole new theory, which I just posted on Facebook, about how to create a new theatrical community with virtual film festivals, virtual critics, Zoom communities, virtual red carpets, and just accept the fact that theatrical is dead. Maybe permanently.

The other possibility for the future is that we will have small film clubs, and they’ll create partnerships with the smart streamers. We’ll start to evolve a new way to do this, and if we want to go out to have a public experience, we’ll pay membership for club cinema, and we’ll go to dinner, and it’ll be like [New York’s] the Metrograph or the Film Forum … What the cinemas are learning, which is why they might survive, is that alcohol is the new popcorn.

I wish they didn’t interrupt the movie to serve it to you.

And I think the next huge challenge is what happens when the surplus of product collapses. We cannot sustain this amount of product in this environment. We’re producing two to three times more than the environment can sustain. I’m gonna be lucky because I have a pre-digital name, but all these young filmmakers are gonna get slaughtered.

Well, it depends how much they can make the movies for.

Even if they make them for nothing, they’re gonna get slaughtered. It’s like baseball. Spring training: There’s probably 200 to 300 young players out there right now who are on the verge of becoming stars who will never become stars and will spend this summer not playing, and by the time next summer rolls around, there’ll be another 200 to 300 kids who want those jobs.

On Facebook, you’ve been musing about finishing your film in some way that does not require you to gather your actors and your crew together again.

If I can create a simulation of the film, and score it, there will exist a document of what I had in mind. I’m having the actors read their lines and doing capture images of them while they do it. I’m having Google capture images of scenes, of locations. I’m learning you can do a lot of things in computers. You can do camera moves. You can do odd cuts. Even though I planned to shoot it in a certain way, what if I just designed it to be a different thing?

That’s fascinating.

Masculin Féminin has always been a very formative film for me. There’s a scene where a guy passes by with a gasoline can and then they hear a sound and somebody rushes back and says, “He just poured the gasoline on himself and burned himself up!” Now, what is that? Is that Godard not shooting a scene, or is that Godard saying, “I don’t need to shoot that scene.” It’s certainly the second: “I don’t need to shoot that scene. It’s more interesting if I don’t shoot it.”

He made that choice, but here that choice is being imposed on you.

That’s the question: If I had to do a prison scene with just voice-over, would people accept it as a choice rather than a compromise? One thing I can control is that I have a composing team — these guys from Annihilation. Geoff Barrow, Portishead — they’re gonna score the film. So if I can create a simulation of the film, they can score the simulation. So that’s a good starting point, and, also, if I create a simulation that is scored, I’ve created a template for how the film should be, should I die.

You’re not gonna die. You’re okay.

We’re all gonna die.

The View From Home

- Whoopi Is Over It

- Meghan McCain Accidentally Made a Great Point About Representation on The View

- Watch Meghan McCain Call Trump a ‘Mad King’ on The View