According to Da 5 Bloods director Spike Lee, part of the reason he and frequent co-screenwriter Kevin Wilmott work so well together is that they are both professors — Lee teaches film at NYU, Wilmott at the University of Kansas. It’s important to keep their academic experience in mind when taking in Lee’s latest Netflix movie, which is both a decade-spanning Vietnam War adventure and a graduate-level course in history and film studies, bursting with references not only to earlier war pictures but important events of the past and present. About a group of black veterans who return to Vietnam years after they served to recover the body of their former commander and a load of buried gold, the film dips in and out of the narrative to provide both flashbacks to the fictional characters’ younger years and glimpses of real historical footage, woven together into a dense portrayal of racism, imperialism, and patriotism. Think of this as your study guide for diving a bit deeper into the story, as we review the names, dates, places, and songs of Da 5 Bloods.

The Cinematic Influences

Lee’s films are frequently filled with references to their inspirations (Night of the Hunter in Do the Right Thing, A Face in the Crowd in Bamboozled, Dog Day Afternoon in Inside Man). Da 5 Bloods is no exception, whether those influences are overt in one instance or subtly woven throughout the film.

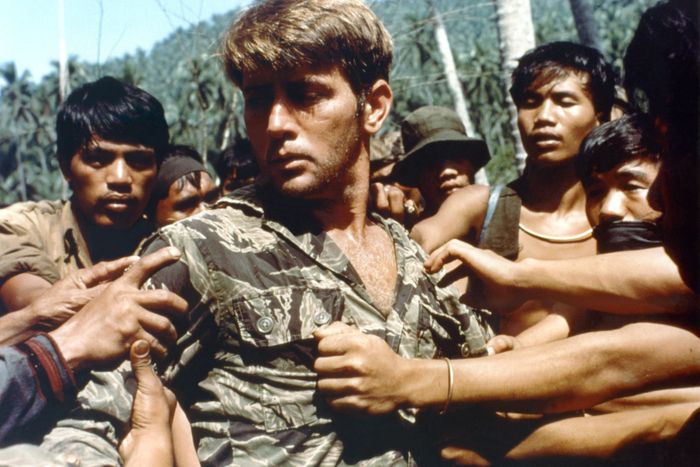

Apocalypse Now

Lee’s film is full of shoutouts to Francis Ford Coppola’s iconic 1979 epic, and for good reason: It was one of the first major productions to dramatize the Vietnam conflict (only four years in the rearview at the time of its release), and did so in a highly stylized fashion that clearly guided Lee’s thinking on the aesthetics of his film. So on the first night of their trip, the four old friends at the center of Lee’s story visit a Ho Chi Minh City nightclub called “Apocalypse Now,” decorated with posters of the film (“That’s a real club!” Lee told Vulture). Later, Lee apes one of the film’s most famous sequences, a chopper attack scored to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” by playing that rousing symphonic number as our heroes set off on their downriver journey (albeit on a slow-moving sightseeing boat). The film also features a young French woman whose family “made several fortunes running a rubber plantation” and a sequence in which our protagonists get a big scare from a jungle animal, both nods to Coppola’s movie.

The Bridge on the River Kwai

Aside from the similarities in style and scope, Lee’s film features a character (seemingly) dying while crying “Madness! Madness!” That same phrase is uttered by Major Clipton (James Donald) while surveying the carnage at River Kwai’s conclusion.

Treasure of the Sierra Madre

John Huston’s 1948 adventure drama is another keenly felt influence, concerning as it does a group of men who discover a fortune in gold and then turn on each other, succumbing to tensions and suspicions. Da 5 Bloods’ second half really cranks up those vibes, with Delroy Lindo as the spiritual successor to Humphrey Bogart’s sweaty, delusional, and paranoid Fred C. Dobbs. And Bloods borrows Sierra Madre’s most famous line of dialogue — you know the one.

Three Kings

David O. Russell’s 1999 war satire told the story of four foot soldiers attempting to swipe a fortune in war gold. While not directly referenced in Lee’s movie, it’s certainly possible the director was inspired by Three Kings — he hired Newton Thomas Sigel, the cinematographer on the movie, for Da 5 Bloods.

Kelly’s Heroes

This 1970 Clint Eastwood vehicle was the WWII version of “a group of soldiers pulls a heist” story, with Eastwood, Telly Savalas, Donald Sutherland, and Don Rickles going after a cache of gold bars in Nazi Germany.

Platoon

Lee often cites Oliver Stone as both a friend and inspiration, and so it makes sense that the flashback sequences in Da 5 Bloods owe much to Stone’s 1986 Oscar winner — both in terms of style (the firefights have the hair-trigger intensity that made Platoon’s so harrowing) and substance (Chadwick Boseman’s character bears a resemblance to Willem Dafoe’s in Platoon).

The Seven Samurai

Lee has called Akira Kurosawa “one of my heroes,” and it’s easy to see the influence of his best-known work here — from the epic scope to the narrative arc to even the construction of the title.

The Opening Sequence

Da 5 Bloods begins with a rapid-fire historical montage, barraging the viewer with names and dates connected to the Vietnam conflict, the protests against it, and the concurrent Black Liberation movement. Here’s a breakdown of that montage:

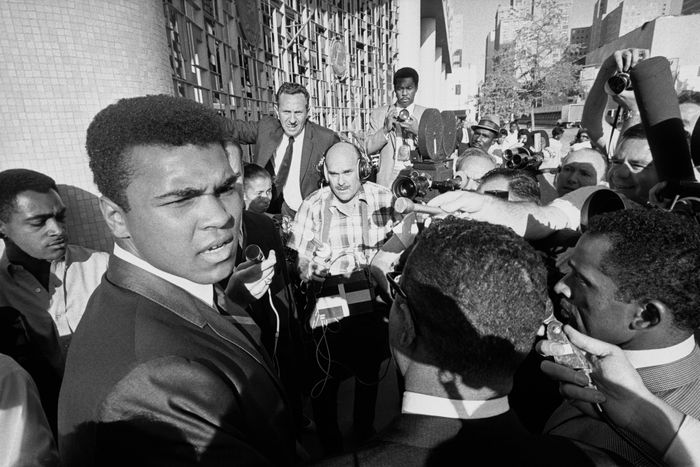

Muhammad Ali

The first clip of the film finds a young Ali, then the heavyweight champion of the world, explaining his refusal to fight in Vietnam. “My conscience won’t let me shoot my brother or some darker people,” he told reporters. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger.” Ali, a devout Muslim, proclaimed himself a conscientious objector to the war; in 1967, he was convicted of draft evasion, and was stripped of his title and suspended from boxing until the Supreme Court overturned that decision four years later.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

Among the images and sound bites of African-American resistance to the war, we see the iconic newsreel images of these two athletes on the victory stand during the 1968 Olympic Games. Smith and Carlos, who had won (respectively) the gold and bronze medals for the 200-meter run, raised their black-gloved fists in the black power salute during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” — an act of protest in solidarity with their brothers and sisters back home, in the name of the “Olympic Project for Human Rights.”

Kwame Ture / Angela Davis / Bobby Seale

Key voices of dissent — of the period, and in Lee’s opening sequence — include Ture (then known as Stokely Carmichael), first a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, later an “honorary prime minister” of the Black Panthers; Davis, the UCLA professor, influential author and speaker, and Marxist feminist; and Seale, the activist and co-founder of the Black Panther Party.

Kent State / Jackson State

Lee also includes footage and photographs from the May 4, 1970 campus demonstration at Kent State University, in which National Guardsmen opened fire on protesting students, killing four. But he also makes space for the less-discussed events in Jackson, Mississippi, 11 days later, in which officers from the Jackson Police Department and the Mississippi Highway Patrol marched onto the campus of the historically black Jackson State University and fired more than 400 rounds into a crowd of students, wounding dozens and killing two.

Thích Quảng Đức / Ho Dinh Van

These two men, captured in shocking photos and newsreels, were among the several Buddhist monks who self-immolated in 1963 as acts of protest against the South Vietnamese government. These suicide protests would continue throughout the war, both in Vietnam and in the United States.

General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan

Among the more horrifying images of the montage are the notorious newsreel film and photograph of the chief of the South Vietnam National Police summarily executing Nguyễn Văn Lém, a handcuffed prisoner, in the streets of Saigon during the Tet Offensive in 1968. That shocking footage, and the photograph of it (shot by the Associated Press’s Eddie Adams) that ran on the front pages of several prominent newspapers, “changed the course of the Vietnam War,” according to the New York Times.

Trảng Bàng Napalm Bombing, 1972

Another key photo, prominently featured here, was shot by AP photographer Nick Ut on June 8, 1972. A South Vietnamese plane dropped a napalm bomb over the village of Trảng Bàng, killing four villagers and children, wounding several others — including 9-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc, whose clothes were burned off by the fiery attack. Ut won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo, which, according to CNN, “communicated the horrors of the war and contributed to the growing anti-war sentiment in the United States.”

The Fall of Saigon

Lee notes that on April 30, 1975, the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong captured the South Vietnamese capital city of Saigon, marking the end of the Vietnam War and what The Guardian would later call “the most crushing defeat in U.S. military history.”

Historical References

Historical and contemporary references come fast and furious in the film that follows — enough to fill a book, but here are a few of the highlights.

President Fake Bone Spurs

The vets’ shorthand nickname for Donald Trump comes from the official explanation for the president’s lack of service in Vietnam. In the fall of 1968, when Trump was a very draft-able 22 years old, a Queens podiatrist named Dr. Larry Braunstein provided (in the future president’s words) “a very strong letter” with a diagnosis of bone spurs in his heels, resulting in a 1-Y medical deferment. Braunstein, the New York Times subsequently discovered, rented his office from Trump’s father, Fred C. Trump.

Blacks for Trump

When his friends discover Paul (Delroy Lindo) voted for “President Fake Bone Spurs,” they jokingly compare him to an African-American supporter who appeared behind Trump at several rallies during the 2016 campaign, holding a “Blacks for Trump” sign. The man in question was later revealed to be one “Michael the Black Man,” also known as Maurice Woodside or Michael Symonette, and a former member of the murderous Yahweh ben Yahweh cult.

Operation Junction City

When discussing their service with their de facto tour guide Vinh (Johnny Trí Nguyễn), they discover that they fought in the same battle as Vinh’s father. Waged in the spring of 1967, it was the largest airborne operation of the war, aiming to locate the elusive Communist Central Office of South Vietnam. It did not succeed — such a permanent headquarters did not exist — and the 82-day battle led to the loss of 282 Americans and a reported 2,728 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese casualties.

Rambo / Missing in Action

In the same scene, the vets discuss the 1980s films in which “Sly” and “Walker Texas Ranger” were “out there trying to save some imaginary POWs” — referencing Sylvester Stallone’s 1985 megahit Rambo: First Blood Part II and Chuck Norris’s 1984 Missing in Action and 1985 Missing in Action 2: The Beginning. Eddie (Norm Lewis) muses of those films, “All them Holly-weird motherfuckers trying to go back and win the Vietnam War,” which becomes a funnier line once you find out where Da 5 Bloods is heading.

Milton L. Olive III

Otis (Clarke Peters) insists he’d be the first one to buy a ticket to “a flick about a real hero,” and gives the example of Milton Lee Olive III, nicknamed “Skipper,” an 18-year-old Black Chicagoan who threw his body over a grenade to save his fellow soldiers during an ambush on October 22, 1965. (This selfless act returns in the film’s climax.) The following April, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor — the first black recipient of the Vietnam War.

Struggles of Black GIs

One of the primary themes of the film is the complicated relationship between the armed forces and African-American soldiers during the Vietnam War — fighting for the humanitarian rights of the Vietnamese people, rights they themselves were not yet granted back in the States. They were disproportionately represented in the conflict (typically serving and dying while their white contemporaries, like Trump, took deferments), and contemporaneous and subsequent reports found that black soldiers were denied promotions, targeted for punishment, and frequently assigned menial duties.

Crispus Attucks

And yet, as “Stormin’ Norman” (Chadwick Boseman), the vets’ commander and spiritual center of the film explains, the first man to die for the red, white, and blue was a black man. He invokes the name of Crispus Attucks — one of five men who died in the Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770, when British soldiers fired into a crowd. As the Associated Press notes, Dr. Martin Luther King name-checked Attucks was well, writing in his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, “the first American to shed blood in the revolution that freed his country from British oppression was a black seaman.”

1619

In that same speech, Norman makes the case for “repossessing” a booty of gold in the name of, among others, “every brother and sister stolen from Mother African to Jamestown Virginia, way back in 1619.” That was, indeed, the year that the first enslaved Africans arrived near Point Comfort in the British colony of Virginia, a key date in the history of white supremacy in America; it’s also become a cultural lightning rod thanks to the New York Times’ Pulitzer-Prize winning 1619 Project and the criticisms of a handful of historians. (Lee, however, has made his allegiance clear.)

Hanoi Hannah

Lee’s flashbacks to Vietnam are occasionally accompanied by radio broadcasts by “Hanoi Hannah,” the nickname American servicemen gave to Radio Hanoi broadcaster Trinh Thi Ngo. She was “North Vietnam’s chief voice of propaganda,” according to war correspondent Don North, who writes that her messages to American GIs — proclaiming the war immoral, encouraging soldiers to frag their superiors and go AWOL, insisting their wives and girlfriends were cheating on them back home — were, as dramatized in the film, frequently aimed specifically at African-American soldiers.

The Riots of 1968

In one of them, “Hanoi Hannah” reports on the outbreaks of civil unrest throughout the United States after the April 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — who opposed the Vietnam War. Protests raged throughout April and May in Baltimore, Kansas City, Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Washington, D.C. “Your government sends 600,000 troops to crush the rebellion,” she tells the black GIs. “Your soul sisters and soul brothers are enraged in over 122 American cities.” Even when Spike Lee makes films about the past, he’s dealing with the present.

My Lai Massacre

At risk of getting into spoiler territory, mention is made later in the film of the atrocities committed on March 16, 1968, in which hundreds of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians — including women, children, infants, and babies — were murdered and assaulted by dozens of American soldiers. Only one of the participants, Second Lt. William Calley, was convicted of a crime; found guilty of murdering 22 civilians, he served only three-and-a-half years, all of them under house arrest.

Operation Ranch Hand

Briefly mentioned in the opening montage and revisited by Delroy Lindo in a searing monologue near the film’s end, “Operation Ranch Hand” refers to the dumping of defoliating herbicides over parts of Vietnam and Laos between 1962 and 1971. The technique was intended to expose the Viet Cong’s trails and roads, but the herbicides — commonly referred to as “Agent Orange” after the color of its containers — caused myriad health problems for both Vietnamese civilians and American soldiers, including birth defects, skin diseases, and cancer.

April 4, 1967

Lee closes his film with a clip of Martin Luther King delivering a speech at New York’s Riverside Church in which he condemned the Vietnam War and offered a five-point plan for ending it. Contemporary media did not respond in kind; an editorial in the Washington Post insisted that King “has diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country, and to his people.” As Lee notes in the film’s closing moments, one year to the day after delivering this speech, Dr. King was assassinated.

The Music

Music is always a prominent part of the mosaic of a Spike Lee Joint, from the score by his frequent collaborator Terence Blanchard to his needle drops — which are particularly pointed this time around.

“What’s Going On”

Marvin Gaye’s 1971 album serves as the unofficial soundtrack for Da 5 Bloods, which features several songs (and alternate session mixes) from the Motown smash. It’s not just a matter of the proper period music; the album, which represented Gaye’s transition from the radio-friendly ’60s pop sounds of “Hitsville” to more topical, intimate material, was a concept record, with several songs told from the point of view of a black Vietnam vet returning to America and trying to make sense of what he sees. But the socially conscious album was also deeply personal to Gaye, whose own brother, Frankie, had served in the war. “The death and destruction I saw in Vietnam sickened me,” Frankie told Marvin’s biographer, David Ritz. “The war seemed useless, wrong, and unjust. I relayed all this to Marvin.”

“Time Has Come Today”

That same combination of deeply felt R&B and social awareness pulses through this Chambers Brothers single from 1967, which plays in the background of a bar scene in the film. But it also has an earlier Lee connection: The song appears on the soundtrack for his 1970s-set Brooklyn memory film Crooklyn.

“(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go”

And finally, again proving that there’s no such thing as “background music” in a Spike Lee film, an intense dialogue scene of the war and its traumas at that bar is scored with this 1970 single by Curtis Mayfield, which directly addresses the turmoil of American inner cities. If the song sounds familiar, it was also the opening theme for the first season of HBO’s The Deuce — and was heard in the Hughes brothers’ 1995 film Dead Presidents, another story of Vietnam vets turning to a life of crime.

The Temptations

Gaye’s Motown label-mates pulled a similar move into more socially conscious music in the early 1970s, and though Lee doesn’t use any of those songs in the movie, it surely can’t be a coincidence that his four returning “Bloods” share names with four members of the group’s mid-1960s lineup: Otis Williams, Melvin Franklin, Paul Williams, and Eddie Kendricks.

Inside Jokes

Subtitles

One of Spike Lee’s strangest writing affectations is his insistence, on his social-media platforms, of writing in headline case — Capitalizing Every Word of Each Sentence, No Matter What. So it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that, contrary to custom, the English subtitles for Vietnamese and French dialogue is Rendered Onscreen The Same Way. (Seriously, it just seems like so much extra work.)

Reunions

The most exciting early news about Da 5 Bloods for Spike fans was the presence of Delroy Lindo, making his first appearance in a Lee film since 1995. That year, Lindo turned in a scorching supporting performance in Lee’s Clockers, with not so much as an Oscar nomination for his efforts. It was Lindo’s third consecutive Spike Lee joint, following Malcolm X and Crooklyn, but they did not work together again … until now. Couple that with the return of Lee’s Red Hook Summer star Clarke Peters and Lee’s sixth collaboration with Isiah (“sheeeeeeeee-it”) Whitlock Jr. (and the fact that Peters and Whitlock are both alumni of The Wire), and you’ve got a movie about a big reunion, which itself features several smaller reunions.