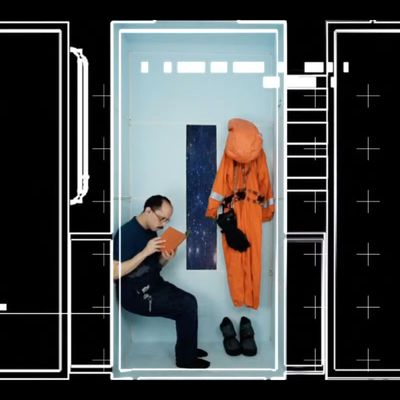

If you are one of the lucky New Yorkers who has a closet, how exactly do you use it? Surely you’re not still just … hanging up clothes? To give you some inspiration: Theater director Joshua William Gelb emptied his closet, painted it white, and turned it into a four-by-eight-by-two-foot experimental theater for solo digital performance.

Gelb isn’t a dancer, but in his so-called Theater in Quarantine, he dances, bracing his body against the walls so he seems to fly; he isn’t an actor, but there he acts in plays about bunkers and spaceships and other such lonely places. Gelb’s YouTube channel has more than a dozen experimental works made in his cupboard-white box, including the 7th voyage of egon tichy, which premiered on Thursday. Adapted by Josh Luxenberg from Stanislaw Lem’s The Star Diaries story cycle and directed by Jonathan Levin, the 35-minute-long playlet imagines a solo astronaut who loses his wrench during a crucial repair and multiplies himself (via time vortex) to get another pair of hands. In the slapstick scenario, too many spacemen soon spoil the spaceship: Tichy’s Friday self wallops his Tuesday self over the head with a frying pan; there’s a three-Tichy scrum for the one pair of boots. The play is mostly an excuse for clowning, but wistfulness penetrates it. Imagine if all you dreamed of was other people, and then those other people — weren’t much help? I certainly make myself lonely; imagine how lonely I’d be if there were more of me.

I still can’t quite comprehend the compositing wizardry that Gelb, Levin, sound designer Florian Staab, and video designer Jesse Garrison managed to pull off here. Though the video is available on YouTube indefinitely, the two captured performances on July 30 were built in real time, with Gelb playing one of the many Tichy-iterations live against 26 pretaped versions of himself. (He explained in a talkback that you can tell which actor is the live one because he’s most likely to be fumbling props. In the 7 p.m. performance recording, look for which Gelb crushes his glasses.) Peiyi Wong’s spaceship set seems, at first, to almost not be a set: Her white panels sit invisibly flush against the sides of Gelb’s closet, with only one green-screen porthole showing the wheeling universe outside. But that makes the space into a puzzle box: Each panel can each be opened out cabinet-door-style, and Gelb can “disappear” behind various configurations of them. Garrison then animates the screen with a black-and-white ship schematic, sliding the image of the playing space around so that Gelb can seem to be crawling “through” his huge spaceship, from chamber to chamber. The video rotates, so one moment Tichy seems to be standing in the tall and narrow galley, the next a long and low airlock. All spaces, of course, are the same space. We’re in that special Tardis-type infinity, a thousand bulkheads bounded in a nutshell.

Nutshells, let’s face it, are where many of us live right now. Not coincidentally, when digital performance moves me these days, it tends to be the pieces about compactness, detail, and the exquisite. Work like the 7th voyage makes confinement a virtue, a prompt to imagination. In the same small-but-mighty vein, I’d recommend the Play Company’s micro-commission Django in Pain, a lovely few scenes of what will one day be a longer work. For the commission, the Mexico City company Por Piedad Teatro made a tabletop puppet show, prefaced with a confession from one of the creators: Antonio Vega, turning a tiny toy house over and over in his hands, talking seriously about his own depression. What follows is a few scenes of Vega and Ana Graham’s in-process puppet piece about Django, a marionette who wants to kill himself, frustrating his playwright’s efforts to write a happy play. Somehow, despite the noose around the doll’s neck, Django in Pain is actually a very buoyant 25 minutes. Perhaps it’s because we always see Django held up by Graham and Vega’s four hands — the stunned and unhappy puppet can’t see them, but we can. All that invisible support! It gives the viewer a sympathetic sensation, as if hands are just above our arms, holding us up too.

Another of my tiny favorites this week was part one of Essays in Idleness, a 14-minute podcast on the category: other audio platform. Tei Blow reads to us, dreamily, from the Tsurezuregusa, Yoshida Kenkō’s 14th-century collection of essays. Kenkō’s work is a flaneur’s harvest of a Japanese courtier’s quiet life, a series of personal essays sometimes dwelling on male physical beauty, sometimes gliding over the idea of etiquette. It is a stream-of-consciousness creation, part of the literary zuihitsu tradition that “follows the brush,” Blow tells us. The podcast encourages you to let your mind work in the same, soft way. In his heat-dazed voice, Blow tells us that sometimes he’ll be changing translations, giving us context, or even falsifying the context … we’ll never know. Does it matter? The episode doesn’t so much end as fade. The brush goes dry, but our thoughts go on, carried by the gesture.