Alfred Hitchcock fell in love with Ingrid Bergman, so much so that he allowed her to boss him a bit, just as his wife, Alma, did — and this film set the tone for all the movies they made together. Bergman was someone who wanted to live in her fantasy life, her creative life, just like Hitchcock did. She understood Hitchcock’s need for distance from people and his fears, and she had a way of smiling that could calm even his deepest anxieties. That’s why he loved working with her so much — but then again, that’s why everyone loved Bergman in the 1940s. It finally came down to that smile of hers, how it could be made to fall away and then how it came back into bloom.

Hitchcock capitalized on his feelings for Bergman in Notorious (1946), which was written by the great cynic Ben Hecht. In thrall to Bergman and her talent, Hitchcock often listened to her thoughts on facial expressions and emotional transitions and let her do things her way if he liked her ideas, which were often good. Hitchcock even let her lover, Robert Capa, take on-set still photographs when she asked for him.

Notorious begins with the exact day and time that it starts, 3:20 p.m., April 24, 1946, when Bergman’s Alicia Huberman emerges from a Miami courthouse after her Nazi father has been sentenced to jail. Cinematographer Ted Tetzlaff gives everything a very spare and queasy look in black and white, so that we are down to visual and emotional essences, and Bergman plays her self-destructive party girl character with abandon.

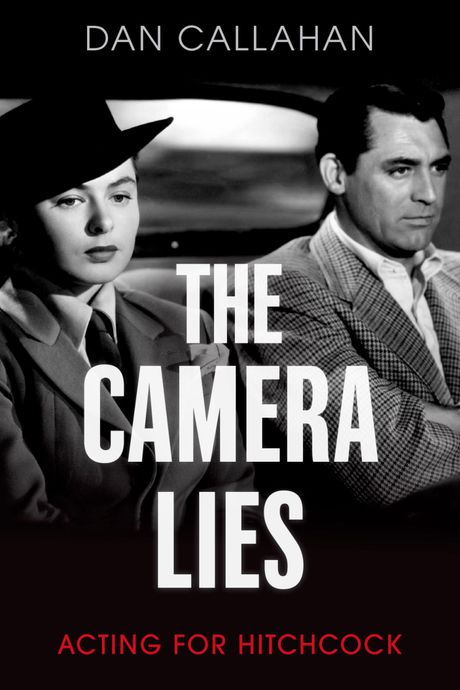

“The important drinking hasn’t started yet,” Alicia tells the guests at her “perfectly hideous party,” which is dominated visually by the dark, sleek head of a man we only see from behind. Alicia keeps coming back to him, as does the camera. The dark head from behind at the party turns out to be Cary Grant’s Devlin, a man of mystery who ties a scarf around Alicia’s bare midriff when they go outside, one of the most erotic moments in any Hitchcock movie, a moment that is charged with sexual anticipation but also Svengali–like control as Devlin fetishistically makes sure the scarf is pulled down just right.

Devlin has come to Alicia with a mission. As the daughter of a Nazi, she is in a good position to spy for the Allies. “Waving the flag with one hand and picking pockets with the other, that’s your patriotism,” Alicia says to Devlin, and there is a thrill in having Bergman say such wised-up Ben Hecht lines. There was something wholesome about Bergman that the public responded to, but this was just a surface reaction. There were many other things going on with her, and many of them had to do with sex. Of course, this got Hitchcock’s full attention.

As the film goes on, Devlin is a man who increasingly cannot keep the way he feels out of his face, but he is fighting with all his strength to do so, and this particular dramatic tension really suits both Grant and Hitchcock. On the plane down to Rio, where most of the story takes place, there is a highly charged, nearly unaccountable moment when Devlin reacts with fear as Alicia moves near him in profile to look out the window. Hitchcock really makes something of this image of Grant’s alarmed face reacting to Bergman’s profile. Is Alicia aware of what she’s doing to him? She seems a little oblivious, but this obliviousness is also one of Bergman’s most ambiguous modes as a performer.

Grant looks under attack here in a way that feels personal, for his Devlin has the air sometimes almost of a confession from this most stylized of actors. It is only in keeping to the fortress of his style that Grant can reveal so much under the surface of his black, glossy hair, that cleft chin, those burning black eyes of his and his thick, needling voice, which matches so well with Bergman’s own Swedish-lilting coloratura.

Alicia relishes the anticipation of something momentous with this great-looking, repressed guy, and she needles him in the way Grant so often needled other people on screen. She puts herself down in a would-be humorous way that only reveals all her pain, calling herself “a little tramp from Miami.”

“I’ve always been scared of women, but I’ll get over it,” Devlin jokes, very seriously. He looks angry at Alicia sometimes for making him feel so much, for hurting him now as sure as she will surely hurt him in the future. The back projection where they sit in a café is out of focus and not scaled very well, but this doesn’t matter. Only those looking at Notorious for the hundredth time would notice such a thing.

The intimacy between Alicia and Devlin grows and she taunts him verbally with her unhappiness and his own. She wants a maid because she doesn’t mind dusting and sweeping but she hates cooking. They go for a walk, and Alicia keeps taunting Devlin until he kisses her very passionately, which was unusual for Grant. Almost always it was women who kissed him passionately on screen while he made himself a moving target.

There is the sense here that sex will have to work through and burn off all the unhappiness in both of these people, and this nearly comes to pass in the famous love scene on the balcony of Alicia’s Rio apartment. Devlin goes out on the balcony and looks at the beach and the ocean coming in and the buildings in the distance. He is a solitary figure, but then he is joined by Alicia, who takes his arm. It is one of the most romantic shots in all of Hitchcock’s work — an oasis, a dream fulfilled.

Devlin doesn’t have to be alone, but he is taking a chance on Alicia. He puts his head next to her head, almost diffidently, or cautiously, and they kiss, Alicia putting her arms around his neck and pulling him in tightly. Bergman keeps caressing and nibbling at Grant and throwing her head back in intense ecstasy while he stays very still and accepts her passion, almost grudgingly. Down deep, Devlin is feeling everything that she is, but he is a man and he has been hurt and he cannot show his feelings. Besides, everything she says about herself is basically true. And yet …

Hitchcock himself wrote Alicia’s murmuring dialogue about making a chicken for them to eat as she kisses and kisses Devlin and eats him up, and these added lines bewildered Hecht, but they bring just the right would-be domestic touch. “No, I don’t like to cook … but I have a chicken in the icebox and you’re eating it,” Alicia says. They will stay in, together, just them. They will not go out. “We’ll eat it with our fingers!” she says, shamelessly, happily. The sexiest thing here is when Bergman caresses Grant’s right ear with an index finger, a moment that is more erotic than any nude thrashing around could possibly be.

This kissing scene lasts two minutes and forty seconds without music. Alicia follows Devlin to the door, her head on his shoulder, unwilling to let him go for a moment. “This is a very strange love affair,” she says. He asks her why, after finally giving her an intense little kiss, and she says, “Maybe because you don’t love me.” She is fishing here, but she is also reeling him in. “Actions speak louder than words,” he tells her. She asks him to bring back a nice bottle of wine (Hitchcock himself was a wine connoisseur).

Bergman is at her very best in these scenes, carefully staying on the fence emotionally as Alicia makes fun of herself but also takes all of her interactions with Devlin seriously and hopefully underneath. Alicia is a woman of appetites, a woman of depth, and she has squandered her gifts deliberately out of self-loathing and loathing for her father. Now she wonders if she might get back to what she was and what she should have been — a nice unspoiled child whose heart, she jokes, was full of “daisies and buttercups.”

Bergman and Grant told Hitchcock that they felt very awkward doing the kissing scene because Hitchcock wanted them boxed in together and unable to let go of each other. It didn’t feel natural to them. But an unnatural show for a camera that usually lies visually expresses in Hitchcock the truth about people and situations. And there was an element of fantasy here, too. Because, as Hitchcock remarked, for the length of this love scene, we the audience are privy to the embrace between two of the most attractive people in the world, enfolded in it with them, vicariously yet also actively.

There is very little musical score in Notorious, which adds to the stripped-down intensity of the film, the mood of which can be very uncomfortable sometimes, like a hangover that leaves you unusually sensitive and vulnerable to noises. The intimacy here between the two actors, between Bergman’s heartfelt and very sensual exposure and Grant’s increasingly powerless, assailed gravity is kept in hushed, rapt balance by Hitchcock. The carnality on display feels like a breakthrough — momentous. Imagine Hitchcock’s buried, stricken feelings as he directed this kissing scene that goes on and on, in love with Bergman and as buttoned-up as Devlin himself.

From The Camera Lies: Acting for Hitchcock by Dan Callahan. Copyright © 2020 by Dan Callahan and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.