➽ HmmmMMMmmm: From Mac Rumors: “The Apple Watch will no longer be counted in podcast listener numbers for Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Tech Lab partners because it has been found to falsely inflate listener numbers.”

Still digging around to figure out the ramifications of this story for big and small publishers. More soon, hopefully.

Counternarratives

Looking back at the past year, it’s reasonable to conclude that Spotify has been successful in controlling its narrative for the most part. Since the Hollywood Reporter dropped that big cover story last November, the company has progressively ramped up the pace of its announcements, whether it was of the dry-but-whoa technical variety (Streaming Ad Insertion, Video, and so on) or of the overtly sexier talent deal variety (Higher Ground, Joe Rogan, Warner Bros). The onset of the pandemic slowed the narrative down a bit, but as we crawl towards the end of summer, it genuinely feels like we’re coming out of a stretch where there was a new Spotify headline popping out every other week.

This press strategy has a “flood the zone” feel, notable for both its ability to create a sense of momentum and its capability, through sheer volume, of drowning out emerging lines of skepticism. There’s always something new coming from Spotify, and that relentless newness has a tendency to crowd out or simply out-date criticism.

Which isn’t to say there hasn’t been any noteworthy dissent. Back in February, the antitrust scholar Matt Stoller penned a strong critique of Spotify in his newsletter, Big, where he sought to illustrate the parallel between Spotify’s efforts in podcasting and what Google did to the web. As strong as that argument was, however, it didn’t really seem to break through. One could perhaps fault it to be too technical or too academic, but either way, when that piece first dropped, I thought I’d be hearing about it more often, but to this date, I simply haven’t.

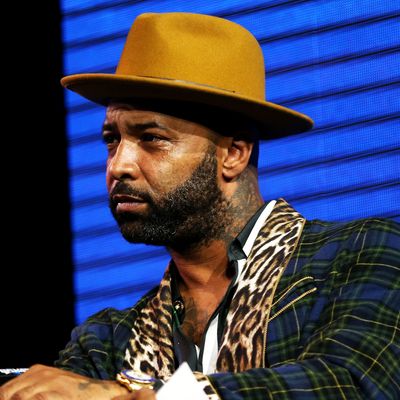

As with matters of political opinion, what’s typically required to drive attention — and swing sentiment — is a sense of spectacle, and last week, we seem to have gotten our very first bona fide spectacle of the Spotify-critical sort, courtesy of the former rapper-turned-media personality Joe Budden.

Last Wednesday, The Joe Budden Podcast, which has the distinction of being one of the first podcasts that signed an exclusive deal with Spotify, dropped an episode containing an extended segment in which Budden vociferously expressed frustration at being, in his telling, wildly undervalued and exploited by Spotify. A veteran of the music industry, Budden proceeded to characterize Spotify as essentially replicating the old power positions of music and the music industry within the podcast context. He framed the story as one where the company was pillaging his audience, evoked a long history of black artists being exploited by (largely white-owned) corporate powers, and accused Spotify of aggressively rendering podcasts as disposable commodities meant to feed its aspirations towards platform monopoly.

“Everybody’s not looking to feed the soil, some are just looking to take the fruit,” he said, building up to the newsworthy hook of the segment: now that his contract with Spotify was coming to an end, Budden declared that he’s all but certain to pull the show off the platform and reject any renewal deal. The gambit was effective as a spectacle, driving a torrent of headlines the next day.

(Some context: Budden’s deal with Spotify was originally signed in mid-2018, shortly before the Swedish streaming platform would embark on its massive podcast efforts. In Budden’s telling, the success of his podcast on Spotify is a big part of what pushed the platform into its current direction, informing what would be the spendy acquisitions of Gimlet Media and Anchor in early 2019 along with everything that came after that. A report in The Information from March supports this reading, noting that the deal brought “hundreds of thousands of new subscribers to Spotify,” and that it was so successful such that CEO Daniel Ek would tell his executives: “Let’s do 1,000 of these.”)

There’s quite a bit more to the specific Budden story, filled with peculiar and ornate details, and though I’ll keep things moving for the sake of efficiency, I’ll say that you don’t have to click around too much to find summaries of it in case you don’t want to spend two hours listening to the actual episode — here’s Vulture, The Verge, Bloomberg, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, Complex, the LA Times, Pitchfork, and HotNewHipHop. (Did I mention it drove headlines?)

Of course, there’s a valid interpretation of this story that principally views it as an effort by Budden to publicly increase his leverage over Spotify in the on-going negotiation over his deal. (Over email, a curious observer compared the situation to a feat of professional wrestling.) While that’s probably true — and while there are other aspects of the Budden segment that could warrant its own scrutiny and skepticism — that still doesn’t necessarily invalidate the criticism he’s laid out.

Indeed, it’s a strain of criticism about Spotify that’s already present among a decent swathe of the podcast community. Based on many, many, many conversations over the months, I can attest that there are many, many, many podcast creators who feel anxiety over (and frustration with) Spotify potentially doing unto on-demand audio what YouTube has done to online video… even if those anxious creators themselves continue to do business with the platform. They don’t typically voice their anxieties in public because they do business with Spotify, but it’s an anxiety and a feeling that’s nevertheless very much present at scale.

The thing I’m wondering is whether this Budden situation actually opens the door for more talent — big and small — to join this public dissent with respect to Spotify. It may very well not, and this story could very well end with Budden signing a souped up deal with Spotify, or with him taking his show elsewhere and us never hearing about this again.

Still, the possibility is interesting. Meanwhile, Spotify presses on, ramping up its dealmaking with influencers and celebrities, bolstered by rumors of offering a seven-figure development deal with Meghan Markle and Prince Harry.

Here Be Monsters Heads Back Out Into the Wild

When I spoke with Jeff Emtman last week, he was hunkered down somewhere in North Idaho, having made an extended pit stop in his big move across the country. There’s been a great deal of change for Emtman, who recently learned that KCRW, the Los Angeles public radio station, would not be renewing its distribution deal with Here Be Monsters, the relatively small but mighty podcast he’s been making for over a half decade.

Emtman wasn’t mad about the decision. “That’s their call to make,” he told me over a crackly phone line. “They don’t owe us anything. It’s not like this was a money-making proposal for them.” Still, he just wished he was given more time. The non-renewal notice came less than a month before the last distribution check came through, leaving him — as well as Bethany Denton, the show’s managing editor and Emtman’s collaborator since 2015 — to scramble for income to keep the lights on.

Here Be Monsters is hard to describe, which is perhaps part of the point when it comes to a narrative nonfiction show that largely (though not always) focuses on the strange, the weird, and the peculiar. Over the years, it’s amassed a vibrant anthology of otherworldly stories, from a profile of an artist who illustrates cadavers to a tale about a book bound by the skin of its author. The pieces are often unsettling, rich, and patiently told. Some come from contributors, though the bulk are produced by Emtman and Denton. The show has more in common with the equally hard to describe Love + Radio — you could say they’re part of the same aesthetic cohort — than with the increasingly voluminous genre of extensively-researched chat podcasts that trade in scary or murder stories and others of the kind. Here Be Monsters is a labor of love, but it takes an incredible amount of labor nonetheless. The predominant sense of the enterprise is one that feels like an effectively run yet painfully small literary magazine.

Emtman started Here Be Monsters in 2012, primarily off a $4000 “community fellowship grant” from Soundcloud. (This, he pointed out joking, was back when Soundcloud still had money. I suppose it’s only fair to correct the record by saying that Soundcloud has new money now, after selling a minority stake to SiriusXM in February, but that’s not germane to this story. Moving on…) That wasn’t a lot of money, but it was enough for him to quit his day job and live frugally while getting the show off the ground.

That grant money funded the first two seasons of the show. Then, in 2013, he aligned with Mule Radio Syndicate, the short-lived podcast network launched out of the interactive design studio known as Mule Designs that once housed John Gruber’s The Talk Show and Audio Smut (later reimagined as The Heart). According to Emtman, that arrangement involved a single ad buy and some cross promotion. The network shuttered in the summer of 2014, leaving the show out of the wilderness once again.

Serial would make its debut a few months later, and the deep wave of new attention it drove trickled down to Here Be Monsters. “People were suddenly looking for other podcasts to listen to, and the podcast ended up on all these lists,” he said. Those list appearances translated to new audiences, and Emtman used those expanded numbers to shop the show around.

That’s when he got the call from KCRW, which offered a distribution deal as part of an opportunity for the show to join the station’s Independent Producers Project. The money wasn’t very much — “not enough to live on, but enough for it to be the majority of what I make” was how Emtman put it — and it would change from year to year, but the terms were minimally invasive, which appealed to him. So he signed the deal, and that was how it was for a number of years. Emtman and Denton would complete five full annual contracts, at twenty episodes a season, before the non-renewal notice came in.

KCRW’s decision to part ways with the show was likely spurred on by the pandemic. The economic fallout has resulted in a budget shortfall at the station, and last month, the We Make KCRW Twitter account made public the fact that station management has formally presented voluntary buyout options as a first step in addressing the financial picture. Bigger moves are expected, as are more surgical ones, like the decision to let Here Be Monsters go. It’s not too much a stretch to imagine that other KCRW-affiliated podcasts could be cut as well.

When I reached out to Paul Bennun, KCRW’s Chief Content Officer, he characterized the move somewhat akin to a rebalancing of the podcast portfolio. “We love Here be Monsters, and we’re sad we’re parting company — but it’s the right thing to do,” he said. “The podcast was supported by KCRW’s Independent Producers Project, which has as its mission finding and amplifying new voices in audio culture. After 100 episodes, Here Be Monsters is well established now. It’s time for us to find new voices, stories and storytellers. KCRW is as committed to this mission and to the IPP as it’s ever been, and we’re excited about what the future holds.”

He added: “It’s normal for stations, services and studios to look at their output regularly and ask how they can serve their audiences better. Even in these hard times, KCRW is entering a time of renewal — we don’t intend to stand still, but to keep pushing forward.”

Emtman is sympathetic to KCRW’s situation, but again, he just wished there was more notice. Nevertheless, the show is back out in the wilds, and he’s still trying to figure out what an independent podcast operation actually looks like today.

He has some ideas. “I’m trying a model for the show that is a bit more akin to community radio, in which local businesses fund the programming,” said Emtman. “In my case, the ‘localness’ isn’t geographic, but local in the sense of the listeners, who are local to the podcast.” He talked about being inspired by public access television, local media, as well as college radio, where he’d hear ads for the very places he’d patroned. To that end, he’s developed a bespoke ad unit for such sponsors, and has so far accrued a list of clients that includes a music album, an indie video game, a dog walking company, a podcast production house, and a shipping logistics company. There is also, customarily, a Patreon.

The money isn’t much at the moment, but the show’s priority right now is simply to reach a place where it can pay for itself while Emtman and Denton pursue contracts on the side to make the rest of their income. It is, undeniably, a tough situation in a tough time, but surprisingly, Emtman expressed a measure of relief. Without the KCRW affiliation, he claims to feel more free now, believing that this new (riskier) independence affords greater opportunity to realize a fuller creative freedom. He speaks of being unburdened by guilt: “I really want to try new formats that I wouldn’t have felt comfortable if I was being paid someone else’s money for that, you know what I mean?”

I suppose I do, though I’m still thinking through the larger takeaway from this story. I feel strongly that there should be a place for Here Be Monsters in the world, and that there should be ways for smaller, stranger shows — smaller, stranger businesses — to opt out of the increasingly industrialized sensibilities of the growing podcast industry. This problem isn’t new, not in the media business nor capitalism, but still, it’s a problem, and many years in now, solutions continue to feel elusive.

Whether it’s his distinct strangeness or some innate hopefulness that I don’t possess, Emtman seems at peace with this. “I think you can boil it down to this: there are podcasts people like and there are podcasts people listen to, and I think you, as a podcaster, have to pick being one of them,” said Emtman. “Then again, if you get the thing you want, then you probably lost artistic credibility, right? It’s a tale as old as time.”

➽ By the way, it’s Upfronts season… and as you would expect in the COVID-19 era, the festivities are all taking place virtually. The IAB Podcast Upfronts is set to take place on September 9 to 11, and it will feature presentations from the usual suspects like Entercom, Stitcher, Wondery, NPR, and iHeartMedia, plus some new additions, like Pushkin and the New York Times.

Here’s a wrinkle: this year, the IAB will be receiving some counter-programming from a new event operation called The X Fronts, which purports to be an upfront event for “independent podcast networks.” Participants include Crooked Media, Talkhouse, Headgum, Wonder Media Network, and QCODE. That takes place later in the month, on September 24.

➽ In other news… Pinna, the paid podcast platform focused on kids programming, is offering six months of free access to teachers and educators. More info here.

NPR hires Aisha Harris, formerly the op-ed culture editor at the New York Times, as the fourth chair of the newly expanded Pop Culture Happy Hour, which celebrated ten years of publishing last month. (Congrats!) That podcast is set to go daily in October.

The Washington Post is increasing production of its Spanish-language news podcast, “El Washington Post,” from two days a week to four. Here’s the official press release on that move.

Sway, the New York Times’ upcoming Opinion podcast with Kara Swisher, is set to debut on September 21, with episodes dropping every Monday and Thursday.

The historian Jon Meacham is launching a new podcast with Cadence13 that’ll spotlight “some of the most important, impactful and relevant speeches in history,” called It Was Said. Kind of interesting in the context of Spotify’s partnership with C-Span to distribute speeches from the two political conventions and the funeral of John Lewis.

Can You Build a U.K. Podcast Business Independent of the BBC?

By Caroline Crampton

In some respects, the UK podcast industry has grown pretty fast in a relatively short span of time. Five years ago, you wouldn’t be wrong in characterizing the place as a mosaic of rehashed radio programmes, legacy media brand offerings, a handful of successful indie shows often (though not always) hosted by comedians, and the rare experimental project that breaks through to a broader audience. Almost everything seemed to be a variation on conversational or interview shows, and for advertisers, there was still substantial doubt that this medium was really worth investing serious money into.

Things have changed quite a bit since then. The runaway success — especially internationally — of My Dad Wrote A Porno did a lot to instill confidence in the format. The BBC’s subsequent move into original podcast development, along with the launch of the BBC Sounds app in late 2018, opened up new and potentially lucrative commissioning opportunities for upstart production companies. And then came Sony Music Entertainment’s investment in two British audio production studios, Broccoli Content and Somethin’ Else, which further signalled the impression that there is gold to be found in these hills.

That’s a lot of activity, but I’ve been getting the feeling for a while now that all these developments seem to cluster around the same kind of path. Plenty of new shows are being made, of course, but the purely professional end of the market seems either to be focused on securing commissions from the BBC (or to a lesser extent, from commercial audio providers like Bauer or Global) or on signing up a celebrity/influencer as a host so that their interview show can attract a big enough initial audience to satisfy wary advertisers. Looking around, there seems to be relatively little being launched at the moment that does not fall into one of these two categories.

Which is why I find Crowd Network, a new podcast outfit that launches in Manchester today, somewhat interesting. “What I didn’t want to be was another production company making content for the likes of the BBC and other big media companies,” said Mike Carr, the CEO of Crowd Network. “I’ve kind of seen that in operation from the BBC side, and those guys make amazing content, but I think the secret of building a big successful company is to make your own content, own your own content and monetise your own content. That’s a model that’s very much in place in America, less so over here.”

Carr might be trying to split with the BBC commission business model, but his company nonetheless has BBC lineage. He himself is a former BBC staffer, having once served as the editor of BBC Radio Sport, and he leads Crowd Network with three other BBC alums: Steve Jones, Tom Fordyce, and Louise Gwilliam. Here’s another way they’re trying to split — but nonetheless have to interface with — the old ways: during lockdown earlier this year, they secured £500,000 in seed funding from Enigma Holdings as well as investment from the comedian John Bishop, who will also soon launch his own podcast with them.

The company is coming out of the gate with an ambition to be “Europe’s largest audio-on-demand network,” and with hopes to address the gap between the US and the UK markets. It also has a founding commitment to developing talent in Manchester — a move that intrigued me when so much of the audio industry in the UK is based in London.

Crowd has an initial slate of seven shows launching before the end of the year, and they have initially partnered with Acast to monetise them. But that’s only the start, apparently. “I don’t think anyone has got the ambition to scale as quickly as we have with a range of titles. Monetising over a period of time, obviously, sponsorship and advertising, but also other revenue streams, live shows if that’s ever possible again, merchandise, potential TV formats, all that sort of thing,” Carr said. The founders had a choice of investors, despite the coincidence of their pitch with the pandemic, with five or six “keen in one way or another” to get involved.

They are, inevitably, going to make some celebrity fronted shows, as the initial partnership with John Bishop demonstrates. They can’t leave that money on the table, because beyond just audience size, there is value for advertisers, Carr explained, in having a well known personality do sponsor reads. “That’s why there are so many of these shows and everybody’s trying to work out different ways of doing interview shows with different celebrities because that’s what the sponsors like — for their products to be endorsed by a David Tennant or someone like that. But there’s only so much of that you can do.”

He feels that the commercial market ought to be able to support standalone narrative series as well, and Crowd’s long term goal is to make a success of something like the recent Missing Cryptoqueen documentary that has been a hit for the BBC. “I would love to be able to say that we’re going to make really high end investigative journalism podcasts, but we’re not in a position to do that yet.” There’s a lot of experimentation going on, it seems — some forthcoming shows have a Parcast-like anthology aspect to them, others a more personality driven approach.

Embedding the company in Manchester’s creative industry was a priority for Carr and his colleagues, who are all based in the city. Their launch announcement even includes a supportive quote from the Manchester City Region mayor Andy Burnham, welcoming the startup to the area’s “£5 billion digital economy.” Crowd is in the process of setting up partnerships with local universities, Carr said, and is committed to hiring people with “the right attitude” rather than prioritising existing skills or experience.

“I think it’s really important that we be judged on this and not just make it window dressing for the launch,” he said. “At the moment, our leadership team is three white blokes and one white girl. We know that we need to change that, and we want to make a difference in that area, both for the benefit of the people we bring in and also for the company. You know, if we just produce content that I like, it’ll all be the same, and that’s the worst thing we could do. You’ve got to get out of that mindset that ‘I don’t like that idea’ when it’s not for me… It’s got to be action rather than words, so we are very much recruiting now.”

One company launch doesn’t make for a seachange in a whole market; I don’t want to overstate this at all. Crowd Network will be judged on its successes over the next few months and years. But there are aspects to their plan that stands out as a fresh development, such as their intent to exist completely outside of the BBC’s ecosystem, to develop talent outside of London, and to keep hold of all their own intellectual property. This could well be a sign of how the UK podcast market is starting to move onto its next phase of growth, and close the gap with what’s been happening in the US.

➽ In tomorrow’s Servant of Pod: I speak with Paul Bae, one of the more prominent operators in the fiction podcast genre — see: The Black Tapes, The Big Loop, Marvels — who is also notable as being part of a growing community of podcast people finding opportunities in film and television production.

Paul is a really interesting guy, in addition to being an exceedingly affable and generous person, He’s lived a thousand lives before this point, having once been a youth pastor, a stand-up comedian, and an actor, among other things. (Fun fact: you’d spot him in The Interview, the Seth Rogen/James Franco 2014 movie that’s perhaps better known as an international incident.) Talking with him, it’s hard not to be struck by how he exudes a strong sense of gratitude; that he’s happy just to be here. Paul’s never short with stories, though I get the feeling I’m only seeing the tip of the iceberg.

I reached out to Paul principally because I was interested in his perspective on the deepening relationship between podcasting and Hollywood: why it seems like studios are increasingly interested in the medium as a farm for intellectual property, what this means for producers native to the space, and to what extent should this dynamic be viewed as an opportunity and as a risk. There’s quite a bit more beyond that, and I’m excited for you to hear it.

You can find Servant of Pod on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or the great assortment of third-party podcast apps that are hooked up to the open publishing ecosystem. Desktop listening is also recommended. Share, leave a review, and so on.