The New Museum’s show “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” finds terrible beauty in the pain, rage, mania, and sorrow that form the continuing psychosis of this country’s obsession with race. Featuring 37 Black artists working in the United States from 1964 to today, it plumbs the long American night of racism with an eye on the poetics of abstraction, the possibilities of monochrome, and the documentation of bare facts. Together, these 97 pieces suggest Black artists have made the most important art of our time.

It’s notable that this exhibition, with its themes of mourning and loss, was the last organized by the great Nigerian-born, Germany-based curator Okwui Enwezor, a visionary pioneer of international multiculturalism, who died of cancer in 2019 at the age of 55. Part of the big global art world that self-started in the early ’90s, Enwezor’s animating purpose as a curator seemed to be to declare a war on the apartheid within the institutional art world, which simply left artists from Africa out of exhibitions. Above all other curators of his generation, Enwezor brought contemporary African art and history to bear on the whole world, and he was unabashed about wanting power so that he could effect change. The show was incomplete at his death and has ably been brought to fruition using notes from and conversations with Enwezor by curators Naomi Beckwith and Massimiliano Gioni, artist Glenn Ligon, and independent curator-writer Mark Nash.

Enwezor’s curatorial eye centered on an erotics of form, color, and structure; even the most difficult or didactic work in this show is packed with its own intellectual and visual pleasure. Unlike with similar exhibitions, you will not spend your time laboring over gassy wall texts. The U.S.-based artists Enwezor worked with are now well known, and that can make this show feel a little orthodox and official in its selections — until you remember, of course, that he helped bring many of these people to light. There are important artists Enwezor has previously highlighted not included here, including David Hammons, Adrian Piper, Wangechi Mutu, and Gary Simmons; he may not have thought their work fit the theme, although we will never know. For Enwezor, what was most important was always how well artists worked with subject matter, rather than the “goodness” of the subject matter itself.

Sometimes this show tears your heart out; other times, it is like a resurrection. For both these emotional states, start with Arthur Jafa’s seven-minute filmic-montage masterpiece from 2016 just inside the museum’s front door. Titled Love Is the Message; The Message Is Death, it is composed of snippets from YouTube, police videos, gospel performances, television, and science films. This alchemy of Black inspiration and pain, born of and despite sick-at-the-core America, should have won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Just off the second-floor elevator is Nari Ward’s ugly-beautiful 1995 gut-punch installation Peace Keeper, in which all of Enwezor’s concerns for materials are at work: Inside a huge steel cage, on an uneven bed of mufflers and beneath a gnarled cloud of them, is a tarred-and-peacock-feathered 1986 Cadillac hearse broken in two. The piece is a detonator. In it, we can feel the ghosts of millions of hearses moving through Black neighborhoods in every American city.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s 2019 work The Full Severity of Compassion is a cagelike contraption, painted all-black and hung with gears, gates, and ropes — a cattle squeeze chute, a device used to contain the animals before slaughter; an industrial tool for handling the soon-to-be-dead. Violence is implied more abstractly in Melvin Edwards’s wall works, called “Lynch Fragments,” which he began making in the 1960s. Bent metal, clamps, bars, chains, and spikes are welded into knotty forms that are at once brutal, seductive, and (because of the head-size scale) human and intimate. Edwards’s work shatters the neutrality of high modernism and maps whole new inner worlds and histories.

Photography was perennially one of Enwezor’s strongest suits. This show includes LaToya Ruby Frazier’s extraordinary documentary photographs of three generations of Black women whose lives are bound to the boom-and-bust fate of the industrial town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, the home of what was once a massive steel mill. The work, made in the aughts, conjures that of social-photographic geniuses Gordon Parks and Dorothea Lange, among others — Frazier is that great. Braddock and its people were left for dead; Frazier captures the normalcy of life there — how people come to live with and take care of themselves in the face of national neglect.

Dawoud Bey’s series “The Birmingham Project” gets at what happens when white America intercedes more overtly. It is made up of black-and-white diptych portraits that make explicit the toll of the KKK’s 1963 murders of four black girls in a bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church. On one side of each diptych, we see a black child who is the same age that one of the murdered children was in 1963; on the other side is a portrait of an adult who is the age that child would have been today. This heartbreakingly stripped-down idea turns infinite: Every person who is killed loses not only everything they have but everything they were ever going to have. Bey’s chasm of sorrow becomes almost bottomless.

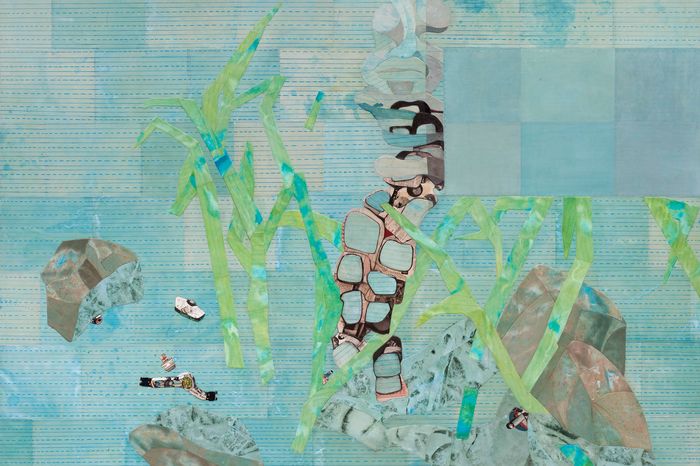

There are also purer forms of abstraction here, such as Ellen Gallagher’s aqua-blue-tinted paintings, their surfaces collaged with children’s notebook paper and snippets from magazines such as Jet that combine to form spinal and cranial shapes. Rashid Johnson’s 2016 installation Antoine’s Organ, the biggest thing on hand, is a gigantic walk-around metal shelving unit adorned with plants, ceramics, TV monitors, old and new books, CB radios, AA bibles, fluorescent lights, raw shea butter, rugs, and a piano on its upper level. With a title evoking the human body, it manages to be simultaneously a reliquary, a shrine, an archive, a funeral parlor, a garden, a living room, and a nature-preserve entertainment unit. It also reminds us that there is no single message to the work here.

Although a handful of newer artists are included in “Grief and Grievance,” the show does not feel forward-looking. It feels instead like a loving last act, a partial summation of the gigantic accomplishments of Black artists over the past 60 years and of Enwezor’s journey with them. This masterly declaration of decades of intellectual independence forms a tremendous canonical portal — one that tasks the art world with continuing what its curator started.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” is on view at New Museum, 235 Bowery, through June 6.

*This article appears in the March 1, 2021, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!