When I meet Nari Ward at the former firehouse on 141st Street where he’s made art for the past 25 years, he apologizes for the fact that the place smells like smoke. His assistant, he explains, had been drilling holes through high school history textbooks for an upcoming project — they reference air holes Ward had seen in the floorboards of a church that was once a station on the Underground Railroad — and somehow the vacuum being used to clean up the book shavings had caught fire. Ward had been miles downtown, at the New Museum, installing his retrospective, “We the People” (which opens to the public tomorrow), but his wife had called, worried; not only is the place his studio, it’s where his family lives.

Ward started working in the firehouse back when the area was considered so inhospitable to gentrification that his landlord promised him the run of the grand old place if he’d just agree to pay the $5000 a year in property taxes. Some of his most well-known works — the room-size installations Hunger Cradle and Amazing Grace — were not only created here but installed here for years, the latter in this very high-ceilinged ground-floor room we’re in, which he currently uses as his studio. Ward finally bought the building in 1999, when his dealer at the time, Jeffrey Deitch, fronted him part of the down payment. “That was a life changer. It wasn’t a lot, but it was still a lot back then,” says Ward, 55, wearing army green cargo pants and a T-shirt, with an ankh dangling from his neck.

The neighborhood is different now, and the artist himself has a complicated relationship to the many changes that accompanied lower crime rates, higher rents, and high-polish, faux-olde-time coffeehouses in the once extremely poor neighborhood. That transformation is, as much as anything, the subject of the New Museum show, which emphasizes his early work and forms a kind of accumulated portrait of this city — his city — over time, and the lives of people of color who often struggle to survive its systemic disregard.

Ward is an accumulation artist: Wherever he goes — Rome, Athens, Vermont — he gathers resonant detritus and transforms it, sometimes with cargo-cult-like handmade effect, into something imbued with memory. He’d originally wanted to call the show “Hunger Cradle,” after a nestlike installation of yarn he first created upstairs in 1996. Various found objects — from discarded bottles to pieces of an expired copy machine to a radiator to, yes, a cradle — are suspended in the yarn, with new items added each time it’s restaged; a soccer ball came from when the installation was in Greece during the World Cup. “I was a little spider, spinning this web” is how Ward describes making the piece, which feels like a metaphor for his appetite and his mind; in some sense, Ward himself might be a hunger cradle.

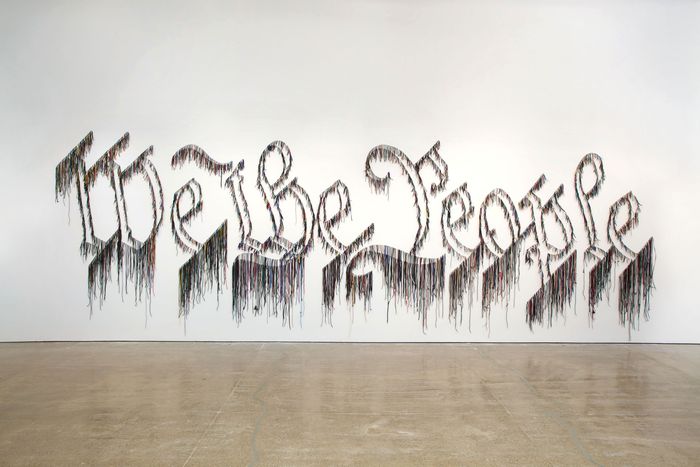

The New Museum curators talked him out of that name for the show, however, convincing him that “Hunger Cradle” sounded too “tragic in a way … like a bad European movie,” Ward says, and might scare off visitors. “We the People” sounds less daunting for sure, but it references another of his pieces, in which that idealistic, nation-building calligraphy is spelled out in sneaker laces that spill from the museum’s wall (inserted in the plaster, I am told, by the same tool used to install a microchip under the skin of a dog). It looks as if the words are bleeding out of the wall. Alongside these works, the show also has a number of pieces that have been in storage for decades, including Carpet Angel, first shown at the New Museum in 1992, and Exodus, which was in the Aperto at the Venice Biennale in 1993.

Ward has the sly accommodating playfulness of a professor, and, in fact, has taught at Hunter College for many years. He was born in Jamaica, but his family moved to Brooklyn when he was little, eventually finding their way to suburban Parsippany, New Jersey, where his mother had been hired by a family to take care of a mentally disabled relative. There, Nari and his brothers spent much of their youth as the only black kids in their classes. He remembers one Halloween when some “kids came dressed as Klan members, and started banging the drum and walking down the parade and pointing to me. They were laughing. I was the only black kid in the school. I didn’t know who to complain to or what to say, and so I was just like, Well, this is how reality is.”

When Ward discovered he could draw, he went to the School of Visual Arts to study illustration, but it got too expensive. He finished at Hunter and got his MFA at Brooklyn College. He was living in the city now, and no longer the only black face, but this brought with it other problems. Since the mid-1990s, he’s had a declaration invoking his Miranda rights — “Notice to Police Officers and Prosecutors” — printed on the back of his business cards. It was inspired partly by his brother, then a lawyer with Legal Aid, who used to have that inscribed on his own cards.

Ward also recalls one particularly harrowing incident from his SVA year that brought home the urgency of knowing his rights. “I was down in the Lower East Side,” he says. “I was walking around, and I saw this guy selling stuff on the sidewalk” — Ward has always been attracted to redolent random cast-off junk, even before he began making art out of it — “and he had some really interesting stuff. And the police came along: ‘Get that stuff and get out of here. Get out of here!’ So, I went from watching the things, to watching the police engaging with him — like it’s theater. I’m thinking, This is interesting, I don’t know anything about this.”

That’s when the police turned to him, presumably because he was a black man who didn’t make himself inconspicuous and just move along, and asked to see his ID. When Ward responded incredulously — he wasn’t doing anything wrong — the cops cuffed him and brought him to the station. The whole thing seemed like a dream. “I was still on the outside of it, thinking, Wow, this is interesting.”

He recalls being brought to a sergeant who took one look at him and instructed the other officers to “put him through the system.” Later, in a holding area, he saw a cop pull another inmate by his dreadlocks and slam his head into the bars on a metal door. “When that guy’s head got hit, I wasn’t just viewing it. I was there. It wasn’t theater anymore. I really got scared at that point. Where could this go?” After the officer saw Ward’s lawyer brother’s card among his belongings, the man’s tone changed. “He goes, ‘Man, you look like a nice guy. Why did you make me do this to you?’”

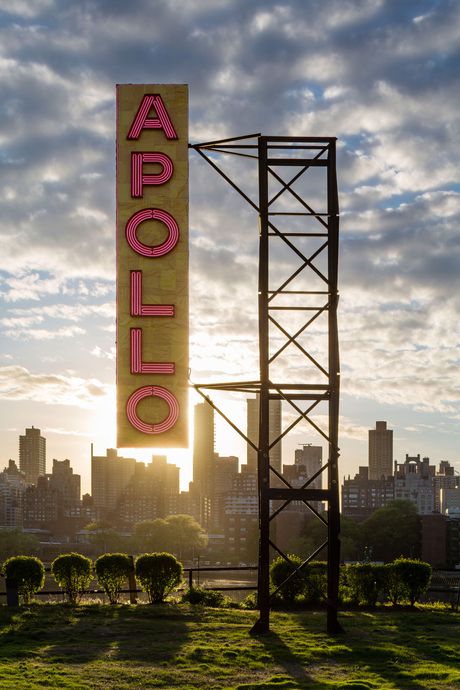

Since then, Ward says he has thought about “how the idea of power gets displayed,” a notion that has fed directly into his efforts to use urban flotsam, whether it’s the 365 abandoned baby strollers — often used by homeless people to cart their belongings around — he collected, one by one, off the streets of Harlem, for Amazing Grace, or the handmade police-surveillance tower he made out of wood and blue tarp, watched over by a taxidermied fox with an afro he named after Cornel West (the original Cornel disappeared after Ward showed the piece at his current New York gallery, Lehmann Maupin, so the New Museum features a stuffed critter dubbed Cornel II he found on eBay), or discarded teaching materials from a nearby school.

As for how this show came about, when I stopped by to watch it being installed, Massimiliano Gioni, the museum’s artistic director, said that seeing Amazing Grace again when he included it in a show he co-curated five years ago about the cultural influence of the year 1993 sparked the idea, but that there was a broader retrospective point to be made as well. “With these shows we want to celebrate the artist, but there also has to be a bit of an argument to be made,” Gioni says. “And the argument we felt could be made about his work was also how he participated in a generation at the beginning of the ’90s, which was part of the beginning of the internationalism of art.”

That internationalization also turned out to be Ward’s big break. Jeffrey Deitch had been one of the curators of the Aperto — the section for younger artists — at the 1993 Venice Biennale. One of the artists he was including, Janine Antoni, had recommended Ward, whom she knew from a residency at the Vermont Studio Center. Deitch went to visit him at his then-studio at the Studio Museum in Harlem. “I was just enthralled by his energy,” Deitch remembers. “He’s one of those artists who everything about him is connected to the work,” he remembers.

Ward went on to have the third exhibition to ever be shown at Deitch Projects, in March of 1996, and “it became a model” for everything they did afterward, Deitch says. It was an installation called Happy Smilers: Duty Free Shopping, named after a band for tourists in Jamaica that Ward’s uncle was in. (Ward has certain themes: He also made a series of “canned smiles” in which he and his children smiled into the bottom of a can — there was a mirror on the bottom — which he then sealed up, as a deadpan commentary on white expectations for black people to be happy.) The centerpiece was a hanging sculpture made from New York City fire escapes, surrounded by debris and fire hoses. “It was quite complicated,” Deitch says, referring to both the salvaging of the fire escapes and to Ward and his friends’ efforts to weld it all together in the space.

But that was a different New York, and a different art world. These days, more often than not, Ward has to get things off eBay, at least in New York. People don’t put as much out on the street, or what they do put isn’t terribly evocative to him. An art-professor friend of his once marveled to him about how their students’ source matériel has changed. Today, Ward says, “the aesthetic is Home Depot.” This is the millennials’ poetic métier: “There’s this availability of matériel that they go and see, and the history of that matériel is what they bring into their practice. But the matériel is dead. It’s corporate.”

Which, one could argue, is a reasonably apt metaphor for what’s happened to this city.

“Nari Ward: We the People” is open at the New Museum through May 26.

*A version of this article appears in the February 18, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!