Millennial pop stars cycle through styles like seasons, in part because, for many of them, the road to recognition ran through kid-friendly outlets that branded them with a stigma it would take deliberate calculations to shake. We got Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, and Christina Aguilera from The Mickey Mouse Club. Ariana Grande got her start on the Nickelodeon high-school drama Victorious. Selena Gomez was the lead actor on Wizards of Waverly Place. The Jonas Brothers blew up thanks to Disney’s The Jonas Brothers and the Camp Rock films (which also starred a young Demi Lovato, who — in a year when we’re learning a lot about what pressures and terrors young stars must endure — has recently spoken up about the abuse she suffered as a teenager). The list goes on. Children are a fickle crowd, and whatever’s popping now isn’t guaranteed clout in perpetuity; for a primer on the experience of weathering these shifts as artists, watch the JoBros’ Happiness Begins documentary, which tracks the trio’s journey from talented preachers’ kids to teen-circuit kings to pop sensations itching to be seen as mature singer-songwriters. Longevity is achieved by growing with your audience. Millennials are the adaptability generation, born in time to experience rapid advances in technology and culture and growing instabilities in politics, finance, and even weather, a generation socialized into since-dated ways of thinking that has constantly had to unlearn and relearn thought processes as science, social mores, and psychology shift.

Pop music goes wherever the national consciousness does, so millennial pop stars are perpetually on the move, reinventing themselves to stay on top of the current sonics and sensibilities, and sometimes just because. Exemplars of this mentality are figures like Taylor Swift and Katy Perry, pop stars who always come back from time off touting new approaches to art and new ways to express it visually. (Beyoncé and Lady Gaga qualify, but you could argue that both career trajectories were patterned after something older, resembling those of multi-hyphenate icons like Diana Ross and Barbra Streisand, singers who navigated impactful film careers, or else restless rock stars like David Bowie and Elton John, who wowed with sights as much as sounds.) Their success on this path has minted constant evolution as the expectation for a long-lasting career on the mainstream charts; consistency grates over time. (It wasn’t always like this. In the ’80s, you could hang out in an era awhile if you liked. See the first three Madonna albums, Prince from 1999 to Sign o’ the Times.) Drake and the Weeknd, whose sense for what specific kinds of songs the audience wants from them is matched only by Adele, stay afloat in pop culture as much through unified, resonant messaging as through their careful rebalancing of the formulas guiding the music. In the same way that network television adjusts to the median morality of the times it reflects, pop stars we met in the ’00s and ’10s are changing their tunes in the ’20s.

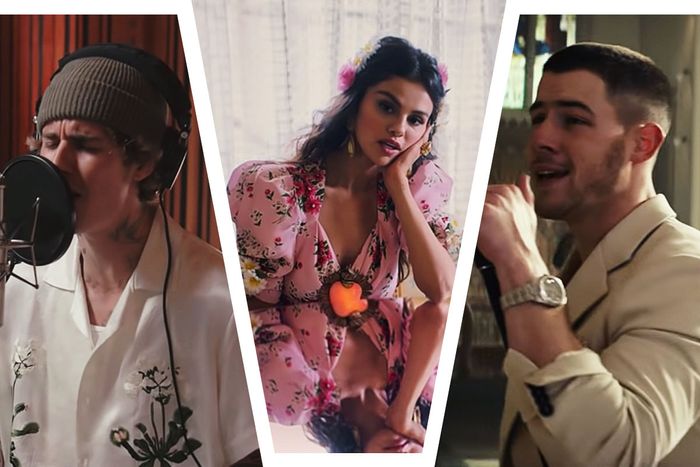

You could see a glimmer of this reality in the way Drake, who is now 34, embraced TikTok last year and the dad-life bars of his new Scary Hours 2 EP, and also in the mature sentimentality and classic-rock airs of Miley Cyrus’s Plastic Hearts. You see more of it in the first batch of notable pop releases of 2021, a batch including Disney Channel aughts alums Nick Jonas (now 28) and Selena Gomez (also 28) as well as YouTube busker turned pop (and more recently, country) radio regular Justin Bieber (27). A year or two ago, you might have caught the three singers populating the same playlists with differing approaches to the same core EDM-pop-trap fusion. Outside the family band, Nick Jonas stood out on dance-pop gems like “Jealous” and “Levels,” songs that affix his sensual falsetto to driving, synth-based production, this after an overwrought 2004 solo debut and the shaky, intermittently fun album by Nick and his short-lived pop-rock act the Administration.

Gomez graduated from a band to a solo career in EDM-pop as well, shifting from the too-clean post-Avril guitar pop of her early work with the Scene to the bolder, more personal sounds of 2015’s Revival and last January’s Rare. Justin Bieber got his start on covers of beloved songs, a path that singers like Dua Lipa and Shawn Mendes followed, and crafted one of the previous decade’s finest pop projects in 2015’s Purpose, an album that delivers as slick a synthesis of the major trends in pop and dance music as Taylor Swift’s 1989. This year, they’re moving in different circles. On this month’s Spaceman, Jonas and rock producer Greg Kurstin look back on the works of ’80s rock icons for ideas. The early previews of Bieb’s forthcoming Justice offer genre-bending sounds and uplifting messages. Selena’s new EP, Revelación, sees the singer try her hand at reggaeton.

Gomez, raised in Texas by white and Mexican American parents and named after beloved Tejano singer Selena Quintanilla, has been interested in making a Spanish-language release for many years, but it wasn’t until the standstill of quarantine last year that work began in earnest. Collaborating with música urbana heavyweights Tainy, Jota Rosa, Albert Hype, and Neon16 — whose talents previously converged on Bad Bunny’s X100pre and YHLQMDLG — Gomez uses Revelación to advance the themes of recovery that fueled last year’s Rare while reconnecting with the language she spoke fluently as a child (proving that her smooth verse on DJ Snake’s “Taki Taki” was no fluke). Like Rare, the EP mixes lighthearted odes to the joys of dancing and kissing with empowering songs about overcoming trauma. Party anthems “Baila Conmigo” and “Dámelo To’” pine for the exhilarating unpredictability of past club nights in the same way Ozuna and Anuel’s Los Dioses depicted such scenes in vivid, nostalgic detail. On both songs, Gomez holds her own with música urbana hitmakers, matching Puerto Rican singers Rauw Alejandro and Myke Towers in both intensity and easygoing melodiousness. Revelación’s best song is its opener, though. “De Una Vez” plays like a follow-up to last year’s “Lose You to Love Me,” as Gomez sings of learning to find peace in oneself instead of seeking fulfillment in others. She’s also learned the value of brevity; not a moment feels wasted. There aren’t enough songs to tire of any of them. Here’s hoping these qualities stick through whatever Gomez does next.

After owning his flaws (and mistakes made while dating Selena) in the meta-apology song “Sorry,” broing down with church pastors, and getting married to Hayley Baldwin, all in the past few years, Justin Bieber is centering love and kindness in his music. Last winter’s Valentine’s Day treat Changes was a honeymoon before life got strange. Unlike that album’s R&B pivot, the imminent Justice seems eager to show there’s no sound Bieber can’t tackle. Every single he’s put out since Changes suggests that his current interests are bringing peace and expanding his artistic palette. “Holy,” his latest Chance the Rapper collaboration, plays the sounds and lyrical conceits of secular pop and praise music off each other (and achieves this with a smoothness that was missing from Kanye West’s rakish pivot from horny dad anthems “XTCY” and “I Love It” to gospel rap in 2019), mirroring the cheeky Christian puns in Florida Georgia Line’s “H.O.L.Y.” Elsewhere, on the piano ballad “Lonely,” Bieber again speaks candidly about making mistakes in public as a teen megastar and the isolating effects of fame, reiterating the message he delivered last fall on Shawn Mendes’s “Monster” and exploring themes of celebrity stan culture and how it feels to be on the receiving end of conditional admiration. Bieber changes course once more on “Anyone,” a love song that weaponizes a massive chorus, adding ’80s pop-rock airs to the growing list of genres the Canadian singer (and recent winner of a Grammy for the remix to country stars Dan + Shay’s “10,000 Hours”) has added to his résumé. These songs are all notably quieter than past Bieber singles; Justice is going to have to bring the noise.

Nick Jonas’s Spaceman might be the most concerted push in the ’80s-production revival happening in the new decade (this side of Miley’s album, which delivered the kind of meticulous period pieces we normally expect from a star like Bruno Mars). Working with producer Greg Kurstin and singer-songwriter Mozella — who last collaborated on the JoBros reunion album — and citing the commercial heyday of ‘d’80s rock stars and former Genesis bandmates Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel as creative inspirations, Nick blends sleek, digitized funk with sedate adult-contemporary pop on his fourth solo album. On the more playful numbers — “Deeper Love,” “This Is Heaven,” and “Delicious” —brash, busy arrangements give Nick room to showcase his keen command of his instrument. The more modern jams are a mixed bag: The vocal on “Heights” recalls Drake, and the beat’s nearly a dead ringer for Whitney Houston’s “It’s Not Right But It’s Okay” (also, Brandy and Monica’s “The Boy Is Mine”). The title track captures the unique anxieties of this era, from loneliness to political uncertainty to COVID woes, delicately and exquisitely.

But just like the Phil Collins catalog, Spaceman runs a little too wan and quiet between the hits. These songs all flow together, zooming from track to track as if the radio station were being changed between them, but there are stretches that are more fit for sleep playlists than as a soundtrack to waking activities. There’s a fine line between music that’s calming and music that is literally sedative; Spaceman delivers a bit too much “Long Long Way to Go” when more “Sussudio” was needed. But that’s fine because in this era of sustained, multilateral celebrity, a miss is an opportunity to recalibrate and return. If Spaceman doesn’t sell well, there are TV shows, movies, and the old group to fall back on. There are endless opportunities to tear up the playbook and start all over again.