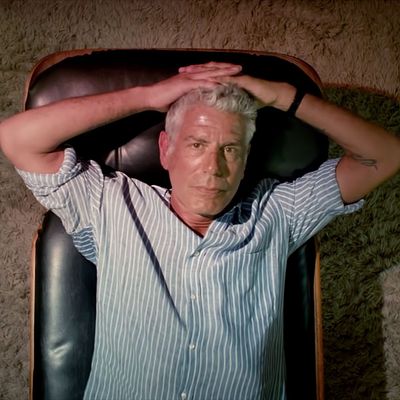

To those who knew him most intimately, Anthony Bourdain was a kind of armchair expert in the minutiae and arcana surrounding famous people who have died by suicide. Over the course of his 18 years in the public eye — exploding out of obscurity as a line chef at New York’s Brasserie Les Halles with the best-selling 2000 culinary tell-all Kitchen Confidential en route to hosting a suite of acclaimed travel docuseries, including CNN’s Parts Unknown — the lanky Manhattanite both spoke and wrote often on the topic. Then, in June 2018, while filming a segment for that Emmy-winning show in the Alsace region of France, Bourdain was found dead at the age of 61.

The new documentary Roadrunner (which arrives in theaters July 16 and will later air on CNN and stream on HBO Max) vividly unpacks the career ascendancy of the roguish truth teller, whose final decades could be fairly defined by their superlatives. A former cocaine and heroin addict, Bourdain traveled the farthest, ate the wildest things, and spent time with some of the most intriguing people on earth.

Roadrunner’s director Morgan Neville (20 Feet From Stardom, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, Netflix’s Ugly Delicious), however, admits he was only willing to delve so far into the circumstances surrounding Bourdain’s death by suicide. Most contentiously, Neville chose not to interview the author-chef’s last girlfriend, Asia Argento — the Italian actress-filmmaker and one of the figureheads of the Me Too movement, who was photographed by an Italian tabloid in what appeared to be the romantic embrace of another man a few days prior to Bourdain’s death.

Although Argento’s limited presence in Roadrunner raises more questions than it answers, Neville insists that speaking to her would have “been painful for a lot of people.” He tells Vulture an interview with Argento would have distracted from the story of what made Anthony Bourdain who he was. “It instantly just made people want to ask ten more questions,” Neville says. “It became this kind of narrative quicksand.”

Before watching your film, I had the question I’m sure a lot of other people have. Anthony Bourdain seemed to lead such a charmed existence. What made him take himself out of it? But I understand answering that question wasn’t the top of your agenda.

I read Kitchen Confidential when it came out, read Medium Raw, and had watched his shows. I felt like I could relate to him. He was a smart, funny ambassador for curiosity. And then when he died, I felt like that doesn’t compute with the guy I thought I knew. Dave Chappelle even made a joke to that extent in his comedy special on Netflix. He was saying the thing everybody wonders, which is, How the hell does somebody who seems to have it all kill themself?

But the thing I was also very leery of in the beginning is for the film to feel like a eulogy; we often read history backward, but we live history forward. And so how do we kind of be in the moment with him? Because there is so much that is funny and exciting. So in a way, I felt excited [to learn] about all this stuff that made him who he was. And then it was the weight of contemplating and understanding his death and then trying to build a bridge from the beginning to the end.

What I came to realize pretty early on is those threads were there all the time. Rereading Kitchen Confidential, there are passages in that book that are pitch black. Where he talks about: “If I get hit by an ice cream truck and they’re peeling the bumper out of my head while I’m dying, I’m not going to wish that I had eaten more or traveled more or taken more drugs. I’m just going to regret how much I disappointed people in my life.” He wrote that in 1999.

There was a trail of bread crumbs going all the way back if you bothered to look for it.

One hundred percent. [In Roadrunner,] there’s a clip for half a second of him floating face down in the pool; it’s from A Cook’s Tour season one. He’s at the Chateau Marmont and has this fantasy of him killing himself several different ways in a hotel, including in a bathroom and then floating face down in the pool. I was kind of shocked. Things like that kept coming up again and again through his shows.

He joked about it. Nobody really understood the depths of that fascination around it. It’d been there for so long people just assumed, “Oh, that’s Tony. He has a black sense of humor.” In Medium Raw, he told this story once — in some raw footage, and we almost put the scene in — of almost driving off a cliff. Around 2004, he had split from his first wife and was in Saint Martin, the island he liked to go in the Caribbean. There’s a mountain pass, and he was drunk. He was going to drive over the edge of the road. And when the Chambers Brothers came on the radio, he decided that was a sign not to and turned the steering wheel.

Tell me about the people you interviewed. Éric Ripert discovered Bourdain’s body in the hotel room in France. He seemed limited in what he was willing to discuss with you, but the fact that he was willing to go on-camera is significant. You also interviewed Bourdain’s wife Ottavia, who seems to have resisted speaking publicly until this point. Did you have to assure people that you were going to take a certain approach — or that you weren’t going to take a certain approach?

In the couple of months after Tony died, several people started talking about wanting to make a documentary about him. And everybody in Tony’s life came together. His agent Kim Witherspoon, CNN, the production company he worked with ZPZ, the estate, and Ottavia. They put out a press release: “We are going to make a film about Anthony Bourdain,” initially as a defensive maneuver just to get people to stop. It succeeded. Nobody else made anything.

But at a certain point, everybody had said, “Okay, if we’re going to make a film, what’s that actually going to look like?” More than a year after he died, I was having a conversation with CNN and they said, “We’re working on this. Are you interested?”

Part of it is, I want to tell a story. I want to feel like it’s the authoritative story, that I would have access to everything. There was a certain feeling among people in Tony’s world that this was a once-in-a-lifetime thing. Ottavia says in the film, “This is the only time I’m ever going to talk about this publicly.” But at least three or four other people said the same thing to me. There was just this sense of, I need to tell the story. I’m going to do it now, and then I don’t ever have to do it again. Several people were reluctant, but they all came around.

Were they protective of him?

Well, yes and no. There’s a moment with David Chang where he hesitates to tell a story, and he’s like, “Fuck it.” He tells the story about what Tony told him about being a father. [In Roadrunner, Chang recalls Bourdain telling him he was unfit for fatherhood.] I feel like Tony was into a kind of brutal honesty, and there was a certain sense of permission in that.

The first meeting I had with Chris and Lydia [Chris Collins and Lydia Tenaglia were executive producers on Bourdain’s shows for 19 years and are founders of Zero Point Zero Productions], I started talking about how important I thought the show was and what they had done and what Tony had done to humanize people in cultures on the far side of the planet. I was going on and they were nodding and finally they stopped me and said, “Yeah, but you have to remember, Tony could be such an asshole.”

I felt like there was a lot of that, Don’t sanctify him. There is so much sanctification that goes on in the wake of somebody’s death where people want to put him on a pedestal. That was so not Tony.

So we’ve talked about who participated. Let’s talk about the person who didn’t participate. Your film puts forward an idea that Bourdain’s behavior as a former addict in conjunction with his tempestuous relationship with Asia Argento brought him to this dark place in his life, where suicidal ideation took hold. But you deliberately did not ask her for an interview. Why?

She’s given interviews. I kind of know what she was going to say. And even as I was putting the story together, as I was trying to make the decision about how to handle it, when I started to put more of that story into the film, it instantly just made people want to ask ten more questions. It became this kind of narrative quicksand of “Oh, but then what about this? And how did this happen?”

It just became this thing that made me feel like I was sinking into this rabbit hole of she said, they said, and it just was not the film I wanted to make. I just want to know why he was who he was and felt like the balance of the film would have tipped over if I had put her in it.

Yes, it would have added a lot of complexity to your job. And you knew what she most likely would have said, but there was always the chance that she would say the surprising thing. Part of your job as a documentarian is to sit there and ask the question and hope that you’re going to get the surprising take.

We debated it for months. I just felt like if I crack that door open, I really better be damn sure it’s what I want. Because it would have been painful for a lot of people, honestly, if I had interviewed her. So I just said — and believe me, we talked and talked about it — is this really what I want?

Again, we played with edits of trying to go deeper into the story and looking at everything she had said. And every time I even screened it for people in longer versions, all I got were people wanting to go down this rabbit hole of more and more about their relationship in the last year of his life. I felt like I’m trying to make a psychological portrait of a person’s entire life. And I just didn’t want to be capsized by it. So I made the call. People can disagree.

Has she reached out to you?

I’ve never heard from her.

I was reading David Chang’s memoir Eat a Peach recently. He goes into Bourdain’s toxic masculinity circa Kitchen Confidential, the sexual relationships that go on around kitchen life. Chang brings this up in terms of the work Bourdain did to improve himself as an individual. You get into some of that, especially in the part of the film about the Me Too era, where Anthony wages a campaign against Harvey Weinstein. But I wondered if this larger idea of toxic masculinity was something you sidestepped?

I know Chang really well. We’ve talked about it. The thing is, Tony went on a kind of mea culpa tour around Me Too, where Kitchen Confidential became kind of this bro manual for guys who wanted to get into kitchen life. It’s kind of like people watching films like Scarface or Wall Street in the ’80s and feeling like they’re how-to movies rather than cautionary tales.

I went back and reread Kitchen Confidential with Me Too in mind, and I think he has nothing but respect for women in that book. The women are badasses in that book. And in a way, I felt like he was being harder on himself than he needed to be. What he was reacting to — which is not really in the book — was more of a kind of permission and a kind of pirate’s life of being in the kitchen.

But Tony himself, I never heard about him sleeping with anybody. I’m not saying it didn’t happen, but, I mean, he was in a very committed, very monogamous relationship his entire culinary career. From the time he was 15 till he was 47, he was in a single relationship with a woman who he really loved. So I don’t think there’s any there there. Honestly.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.