Simon Le Bon is one of New Wave’s beautifully coiffed magic men, serving as the erotic bard of sorts throughout Duran Duran’s celestial ascent in the ’80s, beaming down into Tiger Beat by way of the cosmos, if you will. Along with John Taylor, Nick Rhodes, Roger Taylor, and Andy Taylor, Le Bon, front and center, was one part of the classic-era quintet that grew to define the MTV generation; from “Girls on Film” to “Rio” to “The Reflex,” their roaring synths were inescapable just as much as their polished music videos were on loop. But unlike most of their peers, these New Romantics never stopped making us dance. Fifteen albums and one less Taylor later, Duran Duran is returning on October 22 with their newest album FUTURE PAST, led by the mischievous “INVISIBLE,” complete with a music video created by an artificial-intelligence artist, and “MORE JOY.” It’s a testament to decades of thinking like clever auteurs.

Within minutes of meeting Le Bon earlier this month in Manhattan — a pleasant surprise, given variant this and variant that — he admits he doesn’t tend to have a “retrospective mind,” the recent 40th anniversary of Duran Duran, an objectively excellent debut, be damned. All it takes is a little coaxing and encouragement to get him to humor me and look at his band’s history. Our chat turned out to be equal parts thoughtful of the past and future, with the singer-songwriter offering a warm cocktail of memories that often made him pause mid-sentence and smile. “This was very nice,” he tells me at the end. “No, lovely.”

I’ve been listening to Duran Duran frequently over the past month when I realized it hit the 40-year mark. What’s been your biggest revelation revisiting the album all these years later?

I kind of shied away from it, to be honest with you.

Why is that?

Because there’s so much more; there’s so much stuff to do now. I don’t have a retrospective mind. I tend to want somebody else to do all that stuff and then tell me how great I am.

Would it help you open up if I gave you some compliments?

Probably. [Laughs.] Do you know Michael Penn, the singer?

Of course.

He had a song from the early ’90s called “Long Way Down.” With a wonderful video made by the Brothers Quay. He sings, “Don’t call me Highness because it’s a long way down.” I love that song. And also, “Look what the cat dragged in, he’s got the same dress, but the color’s gone, that I once gave my true love on.” Oh, beautiful words. I relate to them.

Duran Duran has plenty of beautiful words, too, you know.

I mean, I think so. We’ve done a lot, and sometimes it seems like such a long time ago. You kind of wonder, Am I the same person who did all that? Well, physically, probably not. Because your body regenerates over time. Or is it everything except for your brain? That just dies off little bit by little bit. Well, I thank God I picked a simple and easy job, like writing songs, because I probably wouldn’t have enough brain cells for physics. Or quantum mechanics.

But to your initial point, we’ve been working on new stuff, which tends to make you want to not look back too much. One tends to look forward. I’ve immersed myself very much in new music over the last year when lockdown happened. My daughter suggested that I start listening to music again. She said, “You call yourself a musician, you don’t listen to any new music.” And I realized that it started with me coming out of the studio, getting into a taxi and saying to the driver, “Turn the radio off, I’d rather not have any music on.” That ends up with you just listening to the music you’re working on, and listening to the music that got you into a band in the first place.

If I can nerd out about one of your influences for a moment, one of my favorite parts from the 2019 Rock Hall ceremony was when you and John inducted Roxy Music and praised their “pulp science-fiction” sound. Can you tell me more about how they helped shape your musical sensibility?

They were much more an influence on John and Nick than on me. Although I was a big fan, but very much more of their ’74 and ’75 kind of sound. Bryan Ferry, damn. He kind of sang like this, Lala la la dada da.I only realized later how influenced he was by Bob Dylan and his singing style, which is almost like the recitative style. But, well, when Avalon came out … yeah, that was a massive influence. It was just one of the records that was constantly on. For me those records were Avalon and Grace Jones’s Island Life and Nightclubbing, which I could never let go of and still haven’t. You know how quickly things change when you’re a teenager. There was a huge difference between being into Roxy Music in 1975 and being into Roxy Music in 1980.

I find it interesting that Duran Duran had the instrumental “Tel Aviv” and one year later Roxy Music put the instrumental “India” on Avalon.

Oh, do I love “Tel Aviv.” It actually started as a song with lyrics. I’d been on a kibbutz, and just before I left Israel, I went to Tel Aviv and I sat there on the beach and just started writing down some words. Then I came to Birmingham and went to university. I hadn’t heard of Duran Duran yet. It was one of the things that I had written down in my book of lyrics. Tel Aviv to a provincial, suburban English boy — which we all were … pale, pasty white boys from different suburbs of different cities — seemed terribly, terribly exotic. So it became a song. We recorded it as a demo for a “Girls on Film” B-side. But somehow it never developed from there, so it turned into a Middle Eastern–sounding instrumental.

Do you find it odd that Duran Duran hasn’t been recognized by the Rock Hall for induction yet?

No. Not really. I mean, it’s just … they’re their own thing. If they want us, they’ll have us. If they don’t, they don’t. I’m not waiting with bated breath. There’s life to get on with. We have all these kinds of official recognitions that are good and very nice, but one shouldn’t base their self-esteem on whether you’re included or not, because there are many, many other ways of judging one’s success. Notably, the fact that you’ve got an audience who want to hear your music, to me, is a bit more significant. We’re looking at doing an arena tour next summer in America. That’s a big deal for us. That means that there’s a lot of confidence in us playing to a big audience.

I appreciate your perspective on it. Musicians react in all sorts of ways to the idea of the Rock Hall.

I totally get it. I just don’t spend that much time thinking about it; it’s just not really a big deal for me. I wouldn’t even know what to say for a speech. I’d probably be like, “Cheers, thanks for this. Let’s play some music.” Because it’s like, you know, I’m done. On the night that we were there, when we inducted Roxy Music, I was absolutely captivated by the Zombies. I thought they were incredible. Absolutely incredible. Loved it. And that Def Leppard was great too. Great boys. Great, lovely boys.

One of my personal favorite descriptors of the band comes from Nick, who said that he considers Duran Duran to be an “ongoing art project.” How accurate is that to you?

I think you’ve got to be aware that Nick’s life is an ongoing art project. [Laughs.] No, it’s true, though. Because it’s really provided a means of exercising — certainly Nick’s artistic leanings — whether it’s the making of the videos, or the putting together of photo images, or doing the artworks on the covers of the record, or making the music. We do cover some significant art forms. It’s almost like poetry. Well, that might be pushing it a little bit too far.

Hey, Bob Dylan is a Nobel laureate now for “poetic expressions.”

Yeah, that’s brilliant. He’s doing that. Just brilliant.

What does the Duran Duran art movement look like in 2021 compared to 40, or even 20, years ago?

I love our New Romantic period. When you look back at that, you see what an interesting, incredibly innovative, and experimental period of fashion, art, and music it all was. And to happen after punk, it was just so unprophesizable. Nobody would have ever thought that’s what was going to happen at the beginning of the ’80s. It was just crazy. And it kind of just grew up out of nothing. It was people thinking, I’ve had enough of wearing gray and black and dark things [and want] something a bit bright and colorful, and while we’re at it let’s have fun music, something you can dance to. Something you can take the wife to. [Laughs.] I think that’s incredible. We were so lucky, just to be at the right place at the right time, and the mood just flipped. And certain technology had sort of suddenly made itself available to us, like video.

Yeah, that connects well to the music-videology you all embraced from the beginning. It was never about commerce, but artistry.

We weren’t the first people to go heavy on artistic videos. I mean, that has to be said. Russell Mulcahy made a very significant video for Ultravox with “Vienna,” which was very influential on us. We saw that and we thought, Yeah, let’s do something like this, please. Before that, Queen also did a video for “Bohemian Rhapsody.” That was the last clip of that sort I could even think of. And then before that you had stuff from the ’60s, like Paul Ryan’s “Eloise.” He had somebody standing on the beach singing in front of horses at sunset. And then “Bohemian Rhapsody” was basically a performance video of them playing live, with a bit of footage of them standing underneath one light going, “I see a little silhouette of a man.” It was incredibly powerful.

You have to agree that Duran Duran elevated the video medium, though.

We did, yes. When we came along, the first thing Russell did with us was put us on this cinematic matte, which made us look like we were performing on a giant icicle, which I jumped off at the end. It was a totally convincing technical innovation. Well, I mean, matte filming has been around for a long time. But from there, we went to Sri Lanka to shoot the next video. We did “Careless Memories” in the studio, but all of our videos had … they all had little stories. “Careless Memories” was a broken love affair. “Hungry Like the Wolf” was like halfway between Raiders of the Lost Ark and Apocalypse Now. We were taking influence from the cinema and we went on location. We did it. And that’s a huge jump.

You were making short films.

We absolutely were. We got up at five in the morning to start preparing and we would finish up after midnight. We’d go straight home to bed, and we’d get up at the crack of dawn the next day to do it all again. Because it was the only way we could afford to do it. And we did it. It’s funny to think about, in retrospect, because we went to Sri Lanka as a club band. We made the videos in Sri Lanka, which almost arrived in Australia at the same time as we did. And by the time we got to Australia, we were massive stars. It was extraordinary.

Do you feel like you were essentially competing against yourselves to make the best music videos?

I think that’s a very good point, because we couldn’t really step back from it, could we? We had to make one better than the last one. We couldn’t go, Oh, we’re going to take our foot off the gas for a bit now. And we’ll just do something. It won’t be as good, but it’ll still be there. That’s an approach that just would never have worked for us. That’s related to technology, too. “The Wild Boys” is a very significant video for computer graphics. And obviously “The Reflex” is significant, since it’s a live video with an extraordinary effect called “the wave.” A lot of people actually thought that was water and didn’t figure out it was a video effect, because nobody had seen video effects before.

Right now, you take it all for granted that somebody can change into somebody else, and that you can see space and spaceships and things flying around, because we’ve gotten used to the technology, to the CGI. But back then, people didn’t know what to think when they saw this massive wave coming out of the top of the screen. How on earth did they do that? Is it going to hit me?

So you did to waves what the Lumière brothers did to trains.

That’s a nice comparison. [Laughs.]

Who did you consider your video contemporaries during this time?

Not bands. Michael Jackson and Madonna.

I find it fascinating that you all started out by pioneering 35-mm. film for videos, and now you’re the first to have a video made by AI, for “INVISIBLE.” Tell me more about how you conceptualized those visuals.

The video for “Invisible,” which is made by Huxley, is a product of Nested Minds. You need to have a team around you when you’re in an outfit like this; you can’t expect to have every idea to come from the band. This is one that came from our manager, Wendy Laister. She’s very inquisitive. She has a curious mind just like the band does, especially when it comes to the arts. She’s always looking out for stuff that will work with what we do. Like the studio drift thing with the drones that we did at NASA. So she found this company and this extraordinary creation. Somebody referred to it the other day as a software and I said, “It’s not a software. It’s so much more than that.” I mean, obviously it’s not sentient. We think. We hope.

But it does create these images completely by itself. Huxley didn’t take footage of us and render it. Huxley took photographs of us, and footage of how our mouths moved, and created the images. It’s so hard to get your head around, because it is so complicated. Huxley has been designed to be as close to the imagination of the human mind as possible. That’s what they’ve tried to achieve. What it’s done for us is incredible. We’ve got other ambitious projects in the works, too, but I don’t really want to talk about them before they’re even embryonic. It’s kind of asking for failure. I don’t want to jinx it.

You said you don’t have a retrospective mind, so let’s look ahead. What has fulfilled you the most while working on FUTURE PAST?

The pandemic is a very important part of the album and the way it got made. We started at the end of 2018, and after about a year and three months, we thought we were ready to put the album out there. And then the pandemic happened and everything got put on hold. In that time you get a chance to step back and look at what you made from a distance. We were able to say, “I think that could be better. That part there, or that lyric there.” A lot of that went on. But because there was time, it wasn’t such a daunting task. It wasn’t an anxiety-forming process. We had a chance to find some really great featured musicians, like Tove Lo and Ivorian Doll. I also started a radio station last year. It was all about finding new music for me. I got into so many different styles, and so many different genres appeal to me. I love English rap now, especially the female artists … the way the girls talk. That, for me, is the state of the art.

How much of Duran Duran’s past influences its future now?

I think it works on many levels. We are the past and we are our own future. But there’s another way of looking at it, which is that every moment you experience in the future will be a past. So everything you do is a future past. It’s almost like saying the present. I’m obsessed with the idea of existence; of human existence, our consciousness. Like one of our songs says, “Don’t cry for what will never last, each moment in time we create, it’s all a future past that we are living now.”

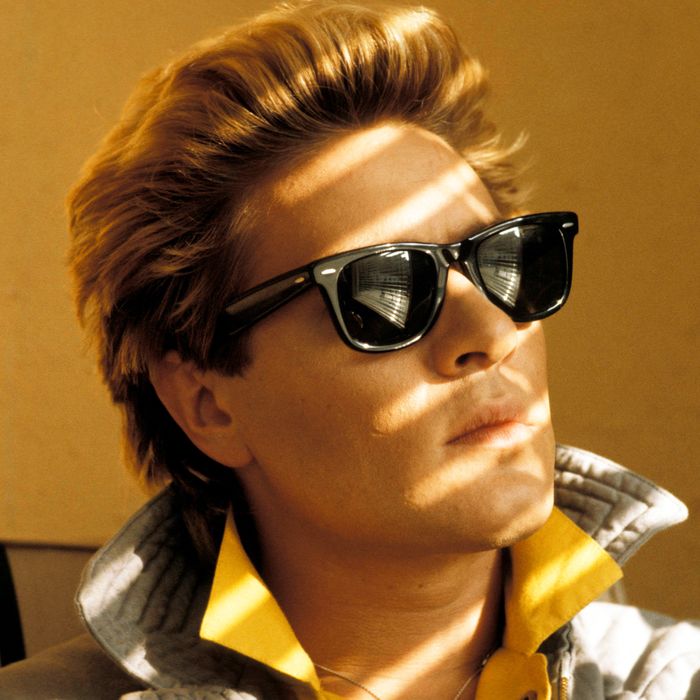

If you would indulge me in one silly, final question: I told a lot of people, both women and men, that I was interviewing you, and they all responded with some type of Oh my God, ask about his hair. Nothing specific, just anything about your hair. So, what’s the secret to it?

I mean, it’s all right, isn’t it?

It’s more than all right.

I’ve got it. [Laughs.] It’s there. I’m very lucky, I suppose. I think it’s because I’m sort of a low-testosterone kind of person. That’s what makes you go bald, isn’t it? It’s how your testosterone decays. I think my testosterone just doesn’t decay in that particular way. I like playing with my hair. I like dying it and I’ve experimented with haircuts. I was so glad to move away from a short back and sides and go for an ’80s mullet. A ’70s mullet, rather.

What’s the difference between a ’70s mullet and an ’80s mullet?

David Bowie as opposed to Simon Le Bon. The ’70s mullet is tighter. Think of Johnny Rotten. That was kind of a mullet, really. A bit longer and thinner at the back and shorter and a bit spiky at the top.

More From The Rocked and Rolled Series

- The Genesis Song Steve Hackett Still Thinks Is a Joke

- Jane Wiedlin Knows the Go-Go’s Could’ve Been Even Bigger

- Kenney Jones Reflects on the ‘Fondness and Sadness’ of His Who Era