In the late 1960s, the photographer David Attie was getting regular work from a magazine called Amerika that few Americans ever saw. It was published by the Department of State, in Russian, and it was distributed in order to show off the good life to citizens of the Soviet Union. Attie was an established if not super-famous magazine photographer who had shot, among many other people, Truman Capote for Esquire and Lorraine Hansberry for Vogue. The assignment he had for Amerika was to document Sesame Street, a brand-new television show that had been designed as an advertising-free educational zone, the first of its kind. Attie spent a couple of weeks on the set (back then, it was on the Upper West Side) catching the actors and the Muppet performers at work. Amerika ran the story with a few nice photos, and the negatives and prints went into boxes in Attie’s house in the East 20s. He seems to have ignored them after that through to his death in 1982, and one can make conjectures about why: This was a backstage story about a PBS kids’ show shot for a government magazine, after all — not exactly a glamour job. On to the next gig.

Thirty years later, Attie’s son, Eli, began looking at his father’s work anew and showing it around to gallerists and editors. (He’s successful in his own right; he wrote speeches for Al Gore and then moved to TV work, where he won an Emmy writing for The West Wing and now works on Billions.) The Capote and Hansberry photos started to get reprinted here and there, as did a few other portraits of famous people. Eventually, Eli made his way to the Sesame Street boxes in his parents’ house, and what he found there was extensive. There were hundreds and hundreds of images, all from the first season of one of the most important shows in the history of television. (Sure, sure, The Sopranos. But did it teach anybody to read?) There are lots of shots of Jim Henson and Frank Oz in unguarded moments, in both color and black-and-white. It’s version 1.0 of the show we know today, the birth of an institution, and they are exquisite documents of an experiment that succeeded beyond its creators’ imagination.

Eli got some of the photos to Trevor Crafts, who was producing the documentary Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street. “Eli sort of very carefully handed us this envelope full of slides, negatives, transparencies,” Crafts recalls, “that were of just amazing things. And we looked through them and knew what their value was.” A few of them made it into the movie, which premiered in theaters earlier this year and is now available on HBO Max. But, being an actual film, it’s largely built out of interviews and motion-picture footage. Now comes the real Attie trove, in book form, The Unseen Photos of Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street, with text by Crafts and essays by Eli Attie and Sonia Manzano, the actress who has played Maria on the show since its early days. And if you are even remotely of 1970s Sesame Street age, you will want to linger over them. The interactions between the cast members — Bob McGrath and Loretta Long, who played Bob and Susan, in particular — and the little kids on set are incredibly tender, and the early, slightly cruder Muppets are startling. (Oscar the Grouch, for this first season, was orange rather than green.) I am almost exactly the same age as Sesame Street, and this is precisely the show I remember from its first few years and mine.

Caroll Spinney, as Big Bird, rehearses with Loretta Long, who played Susan.

Spinney and young actors on the set.

Muppet designer Caroly Wilcox works with puppeteers Jim Henson, Frank Oz, and Daniel Seagren.

Oscar the Grouch was orange before he turned green.

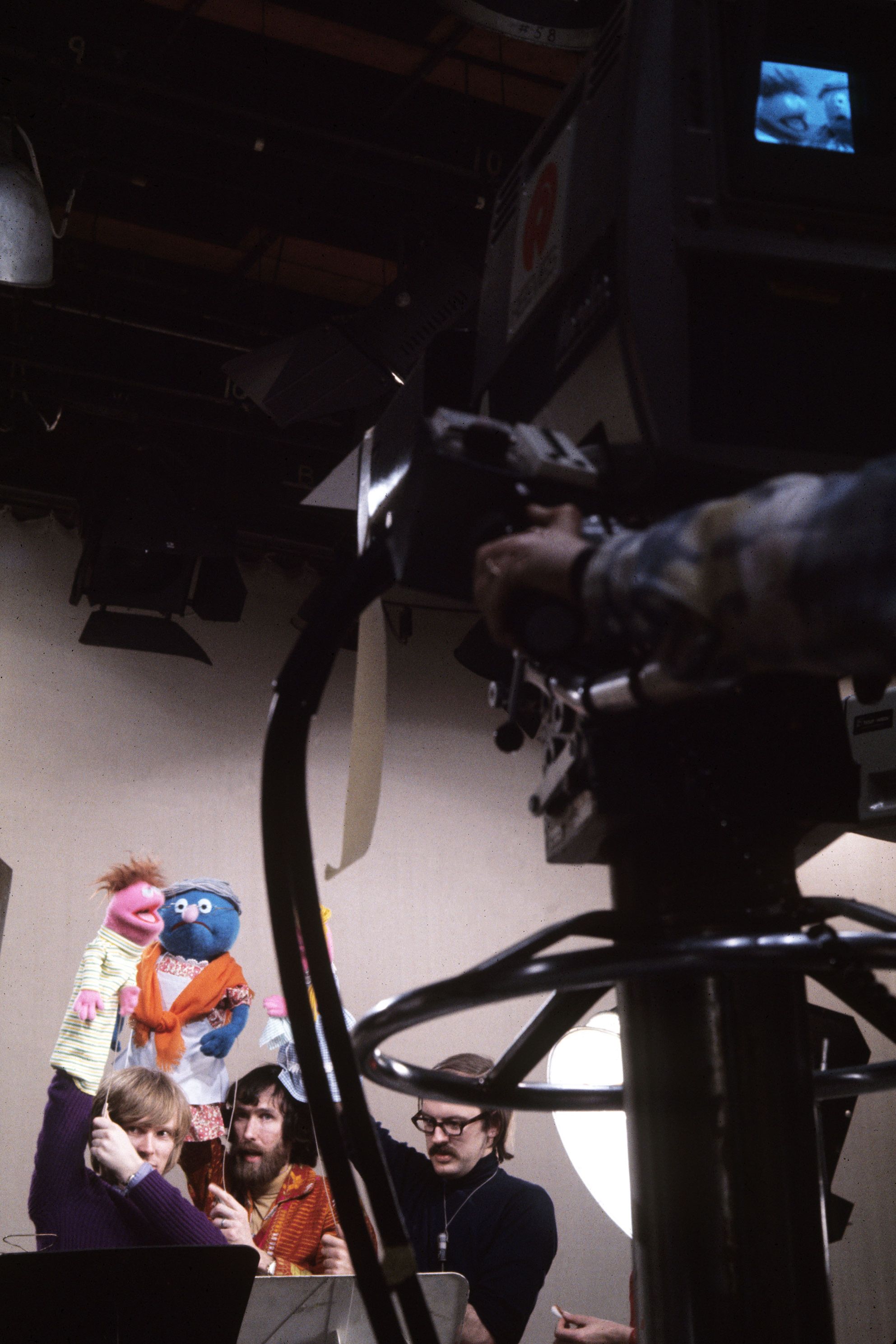

Seagren, Hensen, and Oz (as well as Ernie and Bert).

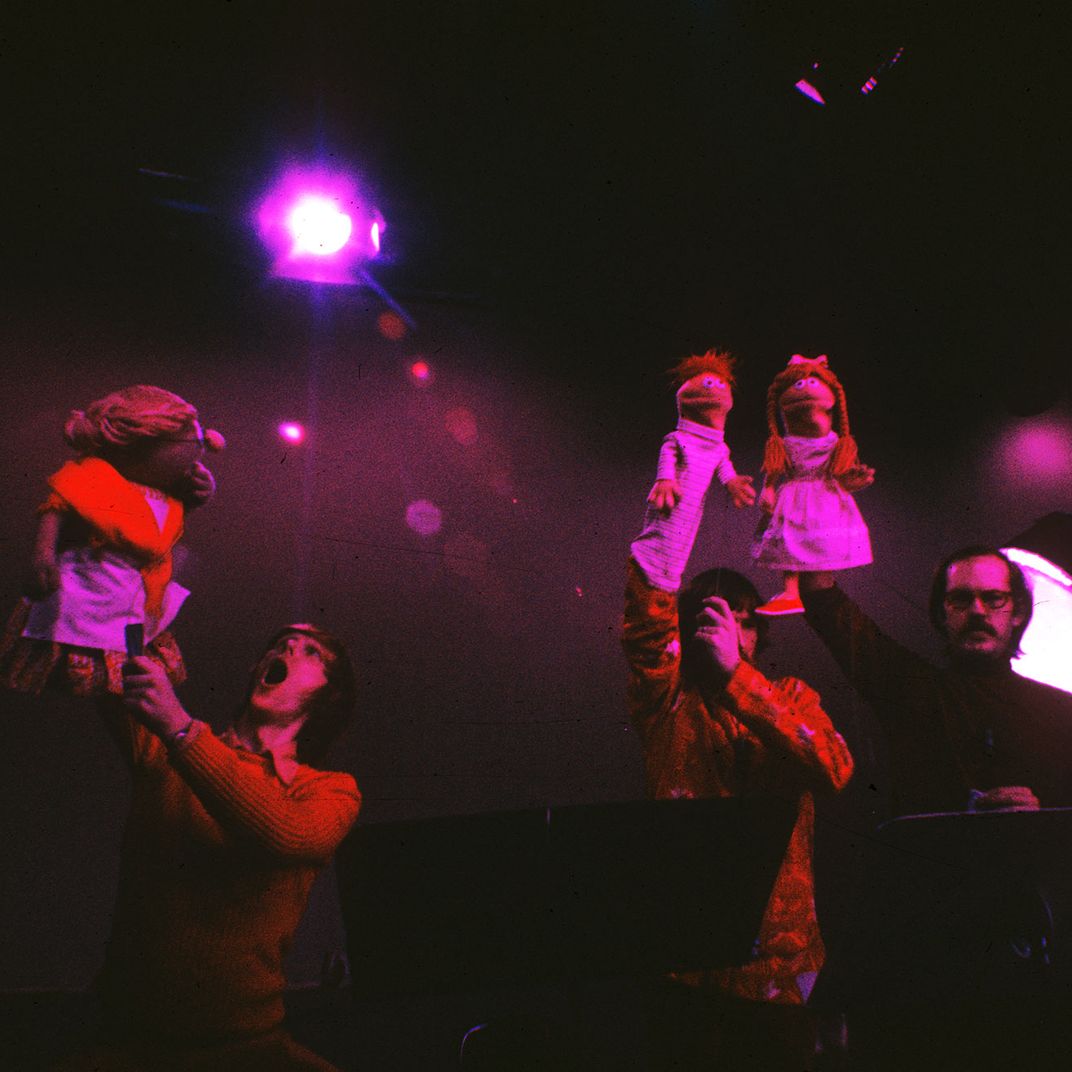

Performing a sketch about the “Hunt for Happiness.”

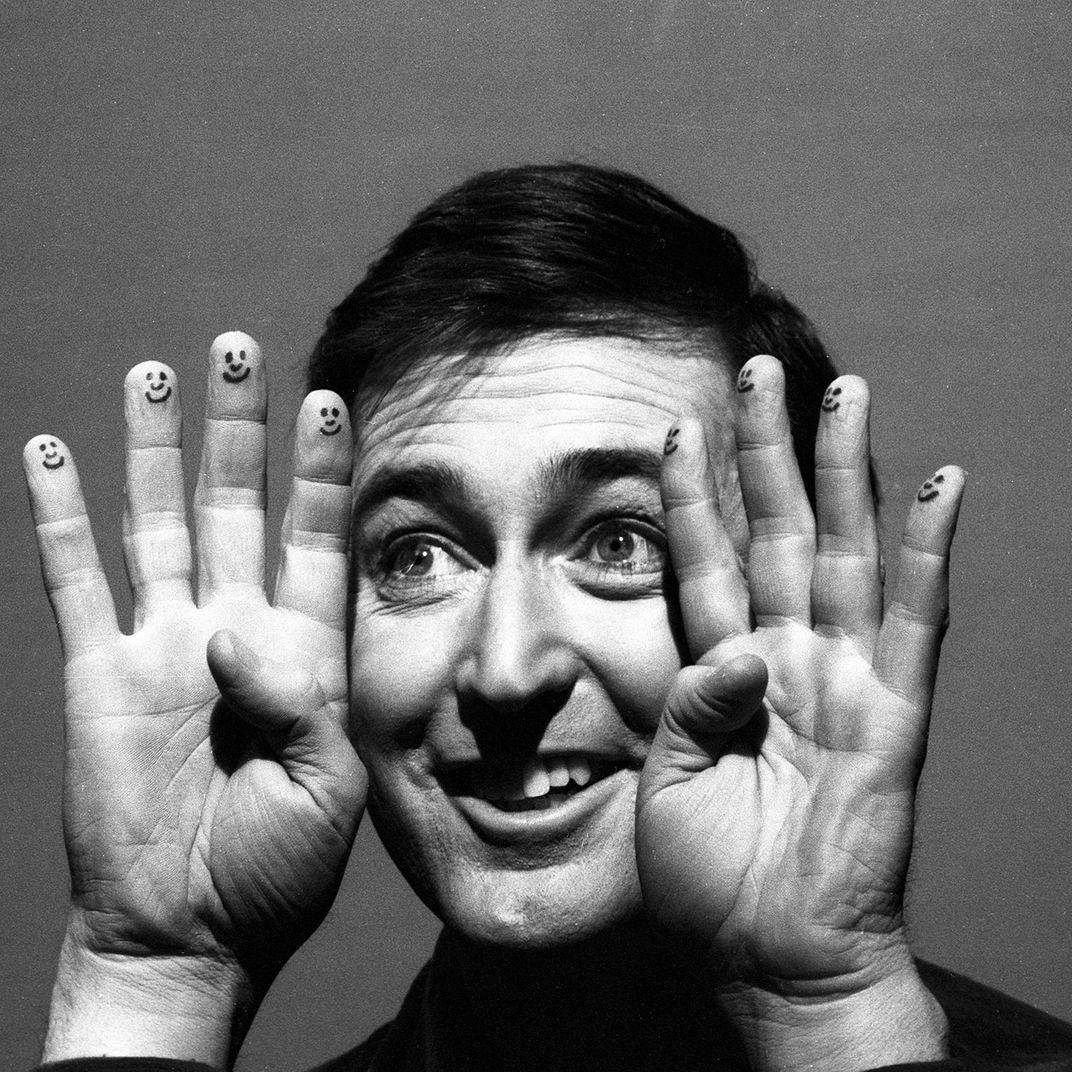

Longtime cast member Bob McGrath.

Attie experimented with color-tinting some of the backstage images.

Spinney, Long, and Matt Robinson, who originated the role of Gordon.

Caroll Spinney, as Big Bird, rehearses with Loretta Long, who played Susan.

Spinney and young actors on the set.

Muppet designer Caroly Wilcox works with puppeteers Jim Henson, Frank Oz, and Daniel Seagren.

Oscar the Grouch was orange before he turned green.

Seagren, Hensen, and Oz (as well as Ernie and Bert).

Performing a sketch about the “Hunt for Happiness.”

Longtime cast member Bob McGrath.

Attie experimented with color-tinting some of the backstage images.

Spinney, Long, and Matt Robinson, who originated the role of Gordon.

You can’t (and I don’t intend to) argue that the Sesame Street of 1970 is better or worse than the Sesame Street of 2021. We live in a different age with different expectations of educational TV; methods of pedagogy have advanced; children themselves respond differently to stimuli, faced as they are with different stressors and habits and family dynamics. (Also, they’ve probably been looking at screens for a couple of years by the time they get to Sesame Street.) What is unmistakable about the old show, however, is that it’s quieter and slower — a lot slower, as the DVDs will tell you — and the difference is palpable even in still photographs. In these pictures, Sesame Street is an experimental project rather than a global corporation, and it looks as unpolished and shaggy. Literally, because virtually all the Muppeteers have long hippie hair.

“There is no glossiness in this work,” agrees Crafts when I mention this quality. The pictures are, he notes, nearly unique: “Sesame Workshop has, you know, tens of thousands of photos of Sesame Street at work, but the reason we wanted to use the David Attie photos was because it is a snapshot of this two-week period of time.” Very few behind-the-scenes photographs of the earliest years exist. “It’s not like what we do today, where we take an enormous amount of behind-the-scenes video for the extra this and extra that.” Joan Ganz Cooney, the show’s co-creator, says in the documentary that they felt confident Sesame Street would run two years — because the team had two years’ funding at the start — and that anything beyond was unknown. They weren’t working for posterity yet.

Eli Attie was very young when these photos were made, which is to say he was of Sesame Street–viewing age. He and his older brother visited the set during those couple of weeks; Eli says he doesn’t remember it, but his brother does, and he even shows up in one episode as a nonspeaking extra. “I have a contact sheet of him in Mr. Hooper’s store,” Eli says. “And I think the way he’s described it to me was that the feeling was very homespun, a little bit rickety. Like, he was very surprised — [Mr. Hooper] gave him what he thought was gonna be a soda, and it was just an empty glass with dust in it.”

One photograph that appears in the book, in fact, conveys the casualness of the backstage scene: David Attie posed before his own camera, clearly just playing around, with the actual Bert and Ernie puppets on his hands. “Here’s what that says to me,” Eli Attie says when I ask him about it. “It says that somebody let my dad — who was just passing through and not some megaconnected guy — put the two most important puppets on the show, maybe other than Kermit, on his hands and take a goofy picture. And my brother’s stories kind of say the same thing: There was a looseness to it. There was an informality — and Henson and Oz were gonna entertain kids in between their 18-hour workday. A kind of a flow, a little bit ‘let’s put on a show.’”