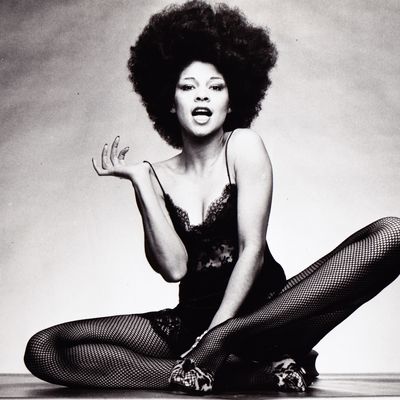

We’ve only ever seen about a minute’s worth of footage of Betty Davis’s live show. The model, musician, and muse, who passed away at 77 last week, married a visionary sense of style to wide-ranging musical tastes and connections, bridging universes of jazz, funk, rock, and soul and expanding the horizons of the men in her orbit. But Davis’s catalogue is frustratingly slight, mostly captured in a string of early-’70s albums that weren’t well received in spite of their general excellence and innovation. In interviews, she explained that she was simply ahead of her time, possessed of a free spirit and sensibilities it took time to warm up to. Betty Davis came on strong. That fleeting, tantalizing tape of the singer-songwriter, producer, and performer shows her tearing through “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes,” off her 1973 debut, Betty Davis. Stalking the stage in glistening thigh-high boots and a bright, tight top and bottom to match, Davis exuded untapped power and unfiltered sensuality, her words erupting from somewhere deeper than her chest. We don’t get to observe this routine being received by an audience, though an episode of Mike Judge’s Tales From the Tour Bus devoted to Davis remembered how these shows literally knocked men in the audiences onto their asses. “I project what the music is saying,” Davis, famously terse, explained in a 2018 interview.

The music spoke volumes. “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes” is a short and jarring tale of glamour and grime that feels almost eerily prophetic: A promising star is dogged by selfish entertainment-industry men until her safety net fails, and she vanishes. Was she recalling breaking up with Miles Davis — by turns a major inspiration and a physically abusive spouse — the pioneering trumpeter and bandleader whose pivot from the stately style of Columbia works like 1963’s Seven Steps to Heaven to the freewheeling, genre-busting exploration of 1969’s In a Silent Way and 1970’s Bitches Brew is an evolution she nudged him toward? Was she frustrated by the successes of friends and rumored romantic liaisons, such as Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, in comparison to the relative disinterest in her own music? Was she already imagining receding from the spotlight a decade after early, abortive attempts to land a chart hit like “Get Ready for Betty,” the mid-’60s confection released under her birth name, Betty Mabry? “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes,” much like the rest of Betty Davis, captures the raw talent of the singer at a crucial juncture, after she perfected the unique blend of funk and rock sensibilities that would inform her 1974 classic They Say I’m Different but before career woes, mental illness, and the loss of her father inspired an ultimately permanent retreat.

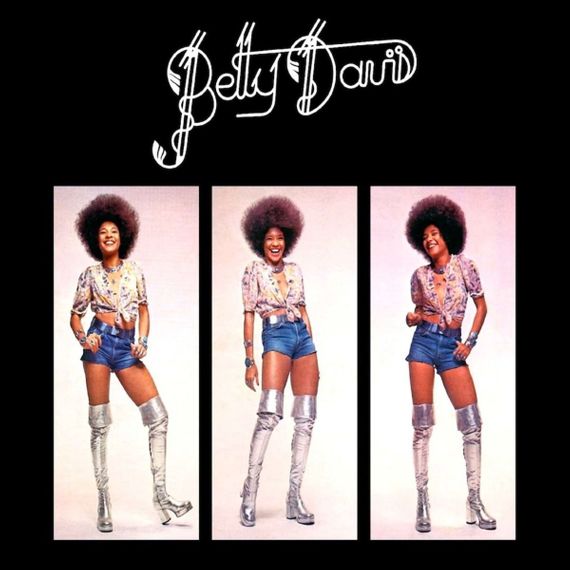

The brilliance and complexity of Betty Davis are apparent everywhere from cover to credits. Beaming out from underneath a radiant Afro on the artwork, the singer beckons to the listener in loud, shiny boots that draw a stark contrast to the rest of the outfit, a summery blouse-and-shorts combo you might spy during a walk in the park on a weekend. Scroll the self-titled’s credits and you catch members of Caravanserai-era Santana, Cali soul group Tower of Power, funk band Graham Central Station, and psychedelic trailblazers Sly and the Family Stone alongside the R&B sibling act the Pointer Sisters and future disco star Sylvester. The intersecting specialties of this collection of players reveal themselves early on in Betty Davis opener “If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up,” Davis’s highest-charting single. The groove is heavy, a fusion of the hard-rock swagger of Mountain’s “Mississippi Queen” and the heady psychedelia of Funkadelic. The voice you hear doesn’t seem like it should be billowing out of the body you know it’s coming from, squealing about fishing for tricks during a night out. Davis was coolly inverting modern musical, racial, and gender conventions, objectifying and infantilizing men for once. Black women had maintained powerful presences in rock, soul, and funk scenes, but in 1973, a few years before the hedonistic sleaze of the late ’70s set in, the guttural, sexual pleas of a song like “Walkin Up the Road” — “I’ve got a feeling / That I’m gonna give you children” — seemed to appall more listeners than it intrigued. Black art exploded in a hundred different directions in those years, but it was also beset by intense discussions about respectable depiction of Black life. Films like Coffy and Foxy Brown gave power to Black female protagonists, though not without complaints about the sensuality on display. For some, Davis was little more than a pornographer selling raunchy sex.

What Davis was really selling was agency. The protagonist wrecking her career in “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes” chose to be nothing, the chorus says. “Anti Love Song” lists in erotic glee all the reasons why the singer will not be taking a man up on his offer to take charge of her life and sends him off with a reminder that seduction can work both ways: “You know, I could possess your body too, don’t cha?” Like a devilish rejoinder to the pimp chronicles of Iceberg Slim, these songs give voice to the dark id swirling underneath our public-showing faces — the shit we’re into that we don’t want anyone else to know about. (They Say I’m Different’s “He Was a Big Freak” is a shining example of Davis’s flair for stark role reversal.) That this art would confound and offend makes sense. Feminism terrifies those who see it as a threat to their existing power dynamics. Poet and activist Audre Lorde outlined the motives for restraining women’s sexuality in the incisive 1978 essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power”: “The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling.”

When we say people are ahead of their time, we are describing our own inability to understand them. It was easier just to call Betty Davis strange and profane than to contend with her music holding up a mirror to highlight how dismissively and recklessly Black women are treated — and how their role in much of 20th-century music (even as solo artists) was often relegated to that of a vessel for male desire. It absolves us of wrongdoing to look at her problems as merely her own and not manifestations of the compound worries of being Black and a woman in America, which “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes” speaks to whenever it isn’t luxuriating in the self-satisfaction and power of stomping through the streets looking like a total delight. Davis got out of Dodge just like her character did, cutting her own path through life as traditional music-business success grew complicated and difficult, because too many men had doubted or mistreated her. Davis had stumbled too soon upon that same self-certain funk that would rocket Rufus’s “Tell Me Something Good” and Patti LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade” to incredible sales while the charms of Betty Davis slipped into obscurity. She dared to deliver it using a gritty, horny tone, to perform in outfits that weren’t demure. It’s easy to look back on this as a mistake that was rectified in the later successes of performers like Donna Summer, who was free enough in that same decade to celebrate bad girls and simulate orgasms, and in the eventual rediscovery of Davis’s albums and the push for her to speak publicly to this history in later years. But we continue to police the expression of desire in music, to legislate what women are allowed to do with their bodies, to dictate who even gets to call themselves a woman. Now we say we’re different, but are we?