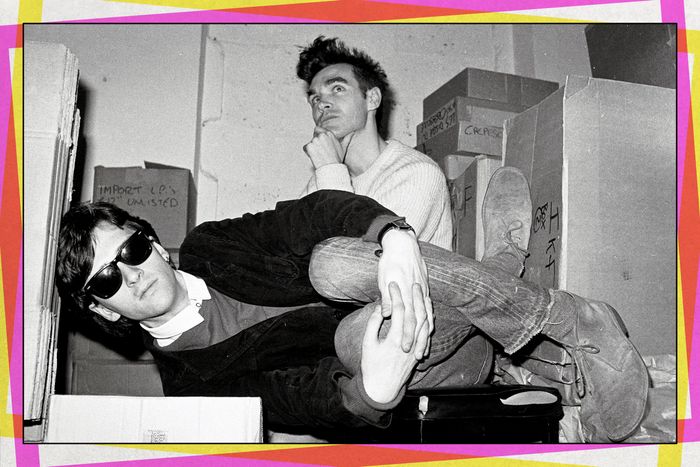

Are you famous enough to be credited with inventing a word? Johnny Marr is — guitarchestra, which refers to the orchestration of a song being built upon five or more guitars at once. It’s the perfect way to describe the “my feelings are larger than my body” sound that the Manchester guitarist first perfected in his most famous band, the Smiths. It also sums up his contributions to Modest Mouse, The The, and the Cribs and his impact on multiple generations of indie music. “It takes a little bit of layering making 14 guitars sound only like ten,” says the 58-year-old Marr, grinning. “But if I was able to do it in the Smiths in 1984, I’m certainly able to do it now.”

This is Johnny Marr: thankful for the past, happy to be here, and excited for the future, which this month includes his fourth solo LP (fifth if you count 2003’s Boomslang with Johnny Marr + the Healers) and first double LP, Fever Dreams Pts 1–4. Ironically, it took Marr a double LP to make his least bloated and most enjoyable solo record yet. Unlike past solo Marr records, whose moments of bliss suffered overall from a sameness of dynamics and tempo (and Marr’s melodies are like sneezes — they come so naturally that they sometimes can be distracting), Fever Dreams is a satisfying balance between his solo guitar work (plenty of fookin’ riffs) and the club-ready dance music he used to make with New Order’s Bernard Sumner throughout the ’90s as Electronic. Marr was a few songs into writing the project, which he’d always planned as a double LP, when Hans Zimmer called him in to help score the new James Bond film. Then the pandemic began. Somehow, he didn’t allow it to affect the project he originally started and proceeded on with Fever Dreams, opting for an uplifting attitude versus total despair or delusion. (Though, as he confesses, he’d hoped the pandemic would be over by the time the record came out.)

“I was determined all the way through the last couple of years to not write a very obvious pandemic record,” says Marr. “But I usually tend to sing about perceptions and feelings and how people are thinking … but because I’m generally an optimistic person, I like for the listener to feel like there’s going to be some kind of positive kind of resolution to this.” He grins again. “I’ve been doing this a long time now, and I love making records. It doesn’t ever get easier. I’m not saying it gets more difficult, but it certainly doesn’t get any easier. I guess it might if you stop giving a shit.” Calling from his home studio in Manchester, Marr looked back on his storied career, the evolution of his guitar playing, and memories with a certain ex-bandmate who shall not be named.

Most guitarchestra moment on Fever Dreams Pts 1 –4

“Night and Day” is the most layered. It sounds like it’s one of the more straightforward indie-pop songs. It’s not unlike the sound that I had with Electronic. But it was a tricky one to layer.

Over the years, I’ve gotten much more experience in getting good guitar sounds. I’m less impatient. When I joined the band the The The in 1988, I had to learn a whole load of new sonic tricks to reproduce a lot of stuff from the early records. And then in Modest Mouse, I was required to make quite a lot of strange noises that they put on in production on some of their previous records. And then, of course, doing the movies. I guess it’s just all experience now, really. Experience and confidence, you know?

First Johnny Marr solo song you’d play for a newcomer

“The Messenger.” It’s a guitar thing that I do — that’s the one with the high-string guitar, which is where you take the high strings off the 12-string set and put them on the six-string guitar. It’s sometimes called Nashville tuning. It’s got a kind of arpeggio guitar. The approach to singing doesn’t sound like anyone but me, which I’m really happy to say.

Your most British melody versus your most American melody

The most British melody is probably “Back to the Old House” by the Smiths because it’s very folky. “Back to the Old House” and quite a few of the early the Smiths stuff is very Irish, so I’d have to include Ireland as well in there, all right?

And the most American? It would be [The The’s] “Dogs of Lust.” It’s slow and dirty. When we made that album Dusk, we were trying to create the atmosphere of an after-hours club in New Orleans or Mississippi in 1971. It was our retro record, but we were trying to create that kind of boozy, funky, sexy after-hours kind of vibe. And we managed to do it fairly well, you know? If you listen to the song “Dogs of Lust,” it’s particularly American. It’s got a real blues harp on it.

There’s quite a lot of things that I’ve done over the years that have got kind of an American sort of tilt to it. “How Soon Is Now?”, the music anyway, was inspired by mostly American musicians and a little bit of Germany. There was a band out of the ’80s called the Gun Club with Jeffrey Lee Pierce, and they did a song called “Run Through the Jungle,” which was a Creedence Clearwater cover. That was a little bit of inspiration behind “How Soon Is Now.” That kind of Bo Diddley, swampy thing is a very American influence, I think.

It’s one of the things that happens about art. Most artists are trying to do something that’s inspired by one of their heroes and they get it wrong, and it’s great. I’m glad I got it wrong. It came out in my own weird stoner-y little Manchester way. The number of bands who’ve tried to try to be Kraftwerk, or Nine Inch Nails, or Depeche Mode, and on and on it goes. The Rolling Stones were trying to be Chuck Berry and it’s great. Aerosmith trying to be the Rolling Stones. The Beastie Boys trying to be Run-DMC. It’s all from somewhere.

Your nerdiest song for guitar players

There’s a few of them, but it’s probably “The Headmaster Ritual” by the Smiths. That’s in an open tuning. I just made up the chords myself, called “J perverted” [laughs]. Before the internet, and when I was a little more secretive, maybe, it was quite tricky for people to work that out. But when people see me doing it plenty live now, you kind of know how it’s done.

A lot of the Modest Mouse record is kind of out there. That was well worked out between me and Isaac. Strictly speaking, everything you hear on the left is me. Most of the things you hear on the right is Isaac [Brock], and then the tubers kind of meet in the middle as well. But almost everything on the left of the stereo spectrum is me. We deliberately kind of worked it out that way, so he’s on one side and I’m on the other.

Most overrated guitar chord

G major. Fucking horrible. G major should be something you do that is in passing. It should be something that passes or helps you get from A to B, you know? It’s like the Starbucks of the chord world. It should be something that you just need to go through to go somewhere else.

Funnily enough, when I wrote “This Charming Man,” I deliberately wrote it in G because it seemed like some of my peers — specifically Aztec Camera, who were our labelmates, so I have a lot of respect — were on the radio, and we weren’t. So I deliberately went, Damn! I have to write something in G. That’s why “This Charming Man” sounds the way it does. It worked! So it shows you what I know. Fucking idiot.

By the way, when you play “This Charming Man” — I can’t remember now — it might technically be in A because I used to tune my guitar up a tone. But essentially, I was playing G chords. So, in my world it was G, but I used to tune my guitar up. But there are loads of songs in G. Lots of Bob Dylan songs. “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” — a song I don’t particularly like. “Honky Tonk Women” by the Rolling Stones, another song from a band I love but I don’t like. Oh, man. So many. That chord is responsible for large and successful sunshine music.

Most satisfying Smiths song to sing

I’d say “The Headmaster Ritual” at the moment. I can relate to the sentiment of the lyrics. I suppose “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want” is probably one I like singing in terms of the way I sing.

I tend to like singing, wait for it, for want of a better term, rock and roll. I like singing kind of upbeat rock songs. I’m not really into being a crooner too much. The singers that I like — or the things that I aspire to, rather — are people like Ray Davies from the Kinks, and Pete Shelley from the Buzzcocks, and Marc Bolan and Patti Smith. Of course, when I was in the Smiths, I absolutely admired it, without a doubt, but I didn’t relate to it because my personality in my life was a million miles away from what [redacted] was putting across. But these days, if I’m going to sing a Smiths song, I almost just feel like I’m the leader, and I’m just starting everybody off. Those songs, certainly at my concerts, seem to belong to everyone. I just feel like it’s a celebration.

Smiths album you wish you could rerecord with today’s technology

The first album! We had the first attempt at it; it didn’t come out because of some politics between [redacted] and the producer, which was a shame, because that was how the band sounded. But, you know, I think he was right in the end. I haven’t listened to it for a long time. And then we rerecorded it with John Porter. But by that time, it had just been overthought and overdone. And knowing now what I do, I would easily make a better job of that first album. That’s the only album that I think sounds not as good as it ought to. I never wanted to mention that for years because I didn’t want to take away from people’s enjoyment of it. I still think it has some good moments on it: “Pretty Girls Make Graves,” “Reel Around the Fountain.” But yeah, if I was being honest, I could do a better job of that.

Collaboration that taught you the most about who you are as a musician

Well, you know, this may surprise a lot of people, but me and Bernard Sumner in Electronic worked for nine years. Even though that was less guitar-y … the actual process of putting records together and arranging — and particularly directing a drummer, and certainly when programming is involved in all of those things, and technology — I learned all of that in my time in Electronic. If you listen to the first chunk of my new album, “Spirit Power and Soul,” there’s a lot of programming on that record, and I’m better at that than I would have ever been in the past. And that makes me happy.

A story from your autobiography you wish wasn’t cut

One is about writing a song with David Crosby. But there’s a great story that I have about the time that Bernard Butler from Suede called me up the night he demoed his first single, which is called “Yes”, which is a song that he did with McAlmont & Butler. And he played it down the phone to me at about 1 a.m. And I was up — I’d like to say I was up just babysitting my daughter, but I was babysitting my daughter and partying at the same time. But she doesn’t care. She’s turned out all right. And she was a baby. And it was such a great moment. First, because I know that feeling, when you’ve just done something that you think is so fantastic, you just want the whole world to hear it. And secondly, that track is still so fantastic that the whole world should hear it. He played that song to me on the phone. He’d just finished it. And I said, “Let me hear that again.” And I listened and I thought, Shit. This is the best track I’ve heard for years, man. And he went, “Johnny? Johnny?” And I went, “Let me hear it again.” And I think he thought I wasn’t sure about it, but I was just marveling at it. It was an amazing moment.

Something about making The Queen Is Dead you’ve never shared publicly

The Smiths have been pretty much done to death really by everyone who was involved, and plenty of people who weren’t. It’s a shame that so much was said without the benefit of maturity and hindsight and that there were so many agendas going around for so many years. But I guess it’s all part of the band’s kind of complicated story.

The truth was that there was loads of love in it. So maybe that’s the story that everybody is missing. Maybe that’s a surprise that everybody who is still interested needs to be reminded of: One of the reasons why they liked the sound of it and why it sounds the way it does is because there’s so much love in it. And there was love in the making of it. There was love in the writing of it. And sure, there was drama, but what you hear was a result of stone-cold love.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From This Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music