Devo is an art movement.

Okay, sure, Devo is also a band, but why define them by a simple noun when they’ve spent more than four decades preaching about anti-stupidity and pro-intelligence, all while looking like a bunch of energy-dome aliens beaming in from their own Spud-nik satellite? Emerging from Akron in 1973, the classic lineup of Gerald Casale, Mark Mothersbaugh, Bob Casale, Bob Mothersbaugh, and Alan Myers critiqued what it meant to be in the New Wave and post-punk genres at the time: They were less concerned about abiding by sonic conventions than finding clever ways to riff about alternative information and entropy, which was exemplified with some of their biggest hits like “Whip It,” “Mongoloid,” and the anthemic “Jocko Homo.” The fact that their songs were catchy as hell was just an added bonus, because it’s statistically impossible not to gyrate to “Whip It” when it starts playing. And if you don’t, well, maybe your de-evolution has begun.

Despite being eligible for Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction since 2003, Devo is only now experiencing its third nomination as part of the Hall’s eligible 2022 class, an honor that is still humbling to Mark Mothersbaugh despite the tardiness. “That’d be nice,” he recently told me over the phone from his art warehouse, a brief reprieve from facilitating a “crazy morning” of deliveries. “Thank you for the positive energy. We’ll see what happens.” With the official induction class due to be announced in May, Mothersbaugh — an accomplished artist and Hollywood composer in addition to Devo duties — was in a reflective mood and, for more than an hour, had an uncontrollable urge to talk about the history of his oddball-music brethren.

Best song

You could ask me on different days and I would have different answers. But if there was one song that was my favorite out of everything, it would be “Jocko Homo.” It was both a theme song and a rallying cry. It was hard-core what Devo was about. We took in a lot of central influences that were not from the world of music necessarily and brought them together. “Jocko Homo” is a visual in a way. When I wrote the song, some of the theory and thought came out of reactionary Christian, anti-evolution propaganda. There was a pamphlet put out by someone in the late ’30s called “Jocko Homo, Heaven-Bound King of the Apes,” and it was attacking and ridiculing evolution. In the process, it was celebrating de-evolution, or at least supporting de-evolution, which we found amusing and entertaining.

Musically at the time, around 1973, my interest was to deconstruct what was considered rock and roll. For me, it started with the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” That was ground zero for rock and roll. So I thought, Yeah, it’s time for rock and roll to say good-bye, and we’re starting something new. We thought it was sound and vision. We were talking about something specific. Jerry, Bob, and I had all been, in different ways, involved with the shootings at Kent State and had been involved with protests that were there. They shut our school down, and Jerry started coming over to my place and we would play music together. But we were talking about what just happened: “They shot 30-some kids at our school and killed four of them. How could that happen?” We were doing something that we thought was important. The idea that we stop dropping bombs on Vietnam. We didn’t feel like that was a good war to be in. We didn’t think there was any reason why we should be over there killing people. I know I didn’t want to go to Vietnam and kill people.

So we started talking about things going backward and going down — they’re not going upward. And in the process, somewhere around that time, I watched a movie called Island of Lost Souls, starring Charles Laughton. He plays a scientist who’s trying to evolve creatures of animals of the jungle. He’s doing experiments on them on this secluded island in the middle of the Pacific called the House of Pain. The animals were all frightened of him. He had managed to make it so some of them could speak and have human characteristics, but they always continued to devolve again after his operations, so he’d have to do more painful surgeries. Part of the control of these creatures was when they started getting confused or angry, he would stand on a rock and crack a whip and go, “What is the law?” And they would all recite the laws: “Not to run on all fours. That is the law. Are we not men?” I remember seeing that and thinking, That’s what we’re talking about in a way of science and religion and anything colliding, and common sense that seems to be sliding away.

Still, to this day, a good portion of humans consider themselves the center of the universe and that their species was meant to rule over the other species on the planet. We were thinking, Well, you know what? Humans are an insane species that’s out of touch with nature. I took elements out of that movie and created the chant “Are we not men? We are Devo!” The music was very radical. What we were doing was art. It was sound and vision in a way that talked about what humans are and why we are here.

I was looking for non–rock and roll with “Jocko Homo.” I put these four blasts that were like clown horns in the verses. I didn’t want my instrument to sound like Rick Wakeman or Keith Emerson, who were doing synthesizers and didn’t really carry any weight or personality. The one person in pop music I felt a camaraderie with was Brian Eno. When I heard his synthesizer solo in the Roxy Music song called “Editions of You,” from For Your Pleasure, it made the hair on my arm stand up. I was like, He’s done it. This guy, we’re of common thought. We had ideas in common. I also put white noise on a wah-wah pedal that opened up and closed during the chorus. It was a sound that was more like an aggressive noise that was keeping a rhythm. I feel that’s Devo at its purest, when we were just pure art.

Most progressive song

There’s things other than sounds that were important to us — part of it was the lyrics. Songs like “Beautiful World” and “Freedom of Choice” have some of my favorite Devo lyrics: “It’s a beautiful world for you / But not for me.” It’s talking about rejecting the cliché of the culture. And “Freedom of Choice” was talking about how we were in an amazing situation where we had freedom to vote, freedom to make choices, freedom to say no to war, and freedom to say yes to taking care of the children in our country or on our planet. And instead, we didn’t. I felt like it addressed those issues, where we did have freedoms that we didn’t even bother using. That was part of the message for “Freedom of Choice.” I thought that was a good message: to use it before you lose it.

Song you wish was as popular as “Whip It”

It would be the more blatant tunes. I think you could say just about anything on the first couple of albums. The lyrics for “Whip It” were very concealed. They were kind of like Thomas Pynchon, who we were fans of. We liked his style, and those songs were kind of written in a Pynchonian way, with the nursery rhyme mixed in with problem-solving. I would say if anything off album one or two had been as popular as “Whip It,” I would’ve really loved that.

Song that challenges listeners the most

That could be “Jocko Homo” because of the timing of it. You can’t dance to it in a typical style, or typical disco or funk or pop-music style. It turns you into more of a dancing ape. There’s such a wide arc to Devo, and early on we were at our most experimental and composed our most outrageous songs. Once we had a record deal, then we switched to thinking, How do you change things in the world if it’s not through confrontation and rebellion? Because they just shoot you if they get irritated enough with what you’re saying. We looked around to see who did make changes in the culture, and it was all happening on Madison Avenue.

In the early ’70s, I painted houses and laid carpets to pay my way through school. I remember being on a ladder one day and listening to Pachelbel’s Canon, maybe the most beautiful piece of music ever written, and there’s lyrics all of a sudden being sung to it for a commercial. I remember thinking, They just took the most beautiful piece of music and made it subversive. And true enough, it was a really successful campaign for Burger King, which was really small on the map at the time. It was such a popular campaign that they did that song in a number of different versions, including country-and-western, easy listening, Singing Nuns, and jazz. All they were doing was convincing people to eat food that wasn’t good for them. I was thinking, Wow, that’s impressive. But they’re doing it through subversion. How could we do that? How could we get people to understand that evolution is real and that humans were leading the charge for the destruction of our planet?

My first year in college, in 1969, I read a book called The Population Bomb. It was a sociologist writing about how humans are replicating at such a fast pace that we will eat our way out of our home within the next 100 years. He predicted that by 2050, a virus will attack humans and will probably take out enough of us so that we don’t become a danger to destroying planet Earth. It still could happen — you don’t know. But it made me think, Well, I’m not going to contribute to the overpopulation of the planet. So I decided I’d never have children. Devo was part of that: understanding that humans had to be aware of what they were doing to the planet. We were more subversive with it and embedded more subliminal messages into our songs.

When Devo slowed down in the mid-’80s, I started doing music for film and television. I was unsure about doing commercials at first. I got offered this Hawaiian Punch commercial, and when I wrote the music, the commercial had one line of dialogue: “Hawaiian Punch hits you in all the right places.” It was robots dancing along with humans dancing. It looked like it was based on the Devo live show. Afterward, I put in a drum fill, and I used a microphone and sang, “Sugar is bad for you.” When I met with the ad-agency people who hired me, I played them the commercial at their headquarters. There was one executive sitting there tapping his pen along with the music, and it goes, “Hawaiian Punch hits you in all the right places. Sugar is bad for you.” As soon as it was over, the executive went, “Yeah! Hawaiian Punch does hit you in all the right places.” He totally missed it. Bob was there with me for the meeting, and afterward he told me, “Jesus, you were so lucky.” I put it at the level where it would get embedded in your head like an earwig but it wouldn’t be loud enough that that was as loud as “Hawaiian Punch hits you in all the right places.” And it was so easy to do. I did that in about 30 commercials or so before somebody finally caught me. [Laughs.]

Most misconstrued song

In our minds, humans were out of touch with nature and insane species on the planet. We were the dangerous species throwing things out of whack. I love “Uncontrollable Urge,” but it was just about energy. It was just about being young and excitable. So I’d say “Beautiful World” because people who did covers of that song seem to always forget that the payoff was the final line, where we sing, “It’s a beautiful world, for you / It’s a beautiful world, not me.” If you saw the video, it was based on all this found footage we included that had men at war and the excesses of capitalism and commercialism.

Most perverse album

Oh, shit. I’m thinking perverse in a positive way. [Laughs.] It would be E-Z Listening Muzak. In the late ’70s, we went out and did a tour that about halfway through coincided with the Saturday Night Live appearance. We were our own roadies and crew until then, and we had to set the equipment up, take it down, load the truck, unload the truck, and do all that stuff ourselves. The first time that we had a crew working for us came soon after SNL. I remember the first show of that part of the tour … we tried not to have opening acts whenever we could because we wanted it to be a true evening with Devo. I remember walking into the venue, and the music starts up while people are coming into the venue. And I’m like, Wait a minute. That’s Tom Petty. Why the hell is that playing? I ran over to the summit and said, “Turn that off. What the hell were you doing playing Tom Petty music at a Devo show? That makes no sense.” And the sound guy goes, “What are you talking about? I have to play music that’ll help me tune the room. I’m not just picking random songs.” Then a Fleetwood Mac song came on after it. I remember being backstage for the whole tour, every single night, hearing these bands that had nothing to do with Devo and had no kindred spirit. And that’s what people listened to before Devo came out onstage!

When we got back home, we said to each other, “We can’t let this happen on the next tour.” So we started recording parodies of our own songs, and we called that collection of songs E-Z Listening Devo Muzak. We recorded more than an hour of songs. “Mongoloid” was arranged in the style of Leave It to Beaver, and we did “Jocko Homo” as a conga-line tune. So for the next tour, we were playing this E-Z Listening Devo Muzak collection, and the sound man said, “Hey, do you have more of those? Kids are coming up to me and they want to buy that tape.” It was just two audio cassettes, I think, and we didn’t have any to give out. After we finished the tour, we went back and asked some managers if they wanted us to make a full album of those songs. It was an immediate no. They were laughing at us. So we countered, “Do you mind if we put it out on Club Devo?” And they said, “Sure, go ahead.” So we made a full cassette of E-Z Listening Muzak that sounded like silly and fake 700 Club songs. We sold quite a few of those cassettes. Warner Bros. got angry about it! They said, “You tricked us.” And we said, “No, you just turned us down.” We ended up putting out a second volume, and that was the music we always played for our opening act back in those days.

Biggest misconception about the band

Oh my God. What would be the biggest misconception? That we — and it was partly because our record company didn’t understand us — were joking and didn’t really believe in de-evolution or the dangers of it. We were making films, and they had told us they thought we were like another version of the Tubes. I think Warner Bros. didn’t really know how to sell us or how to market us, so they called us “quirky clowns” at times in their publicity. We’d be like, Well, I take an exception to that. There were other bands I could have thought of that were really clowns. [Laughs.] We should’ve been marketed as social scientists.

Music video that helped elevate the medium

The “Satisfaction” video kind of introduced the idea of storytelling, as opposed to just baby faces selling something. I think the Rolling Stones — and you’re going to laugh when I say this, but both Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were underrated as lyricists. People talked about other things in their songs constantly, but I think they had brilliant lyrics. I thought there was some kindred spirit between us. We did our version of “Satisfaction” on the tenth anniversary of the song. We chose it because not only did I think it was the best rock song ever written, but also we thought it would help explain to people who we were, what we were doing, and why we were doing it — in the sense that it was very deconstructive and it takes you a while to realize what the song is when you hear our version of it. But it was successful and a fair tribute to Keith and Mick’s song.

Back in the ’70s, you had to get permission to do what was called a “parody” of a song since you were taking liberties with somebody else’s melodies and lyrics. Quite honestly, Johnny Rivers was very unhappy about us doing “Secret Agent Man.” So we did have to play it for someone in the Rolling Stones. It turned out Jerry and I went to Manhattan and visited their manager’s office. Mick came in from a little private elevator. I don’t know where he had been, but he didn’t have shoes. He just had socks on, and we played it for him. About halfway through the first chorus, he jumped up and started dancing to it. That was kind of cool. He still thinks it’s the best cover of that song. You can imagine how we felt. It was a pretty amazing day.

Legacy of the 1978 Saturday Night Live performance

It’s a testimony to how creative SNL was at that time. They were powerful. Everybody watched that show; people were staying home at night so that they could watch it. When we first came out to California, there were a lot of people who wanted to manage us. One particular guy, Elliot Roberts, said he wanted to manage us. We responded, “If you can get us on SNL, we’ll sign with you.” And he did because he knew Lorne Michaels. We already knew that Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi were big fans because we sent them records trying to get them to take an interest, and they did. But yeah, it was a very big deal for us because we were pretty much only known on college radio. The general public had no idea who we were. SNL dropped the bomb on America with Devo, and things changed for us. We were on a tour at the time and saw that half-filled venues were all sold out after that. People wanted to know and confirm what they had just seen.

Unlikeliest Devo fan

There’s people that have what might be considered odd professions or odd areas of study. But, in a way, that kind of makes sense. I’ve met a lot of people who study gene mutations. There was a woman from Harvard University who counseled people who had given birth to monsters. Huge Devo fan. It was her job to talk to them, and she collected the photos of all these monsters that were just awful and horrifying.

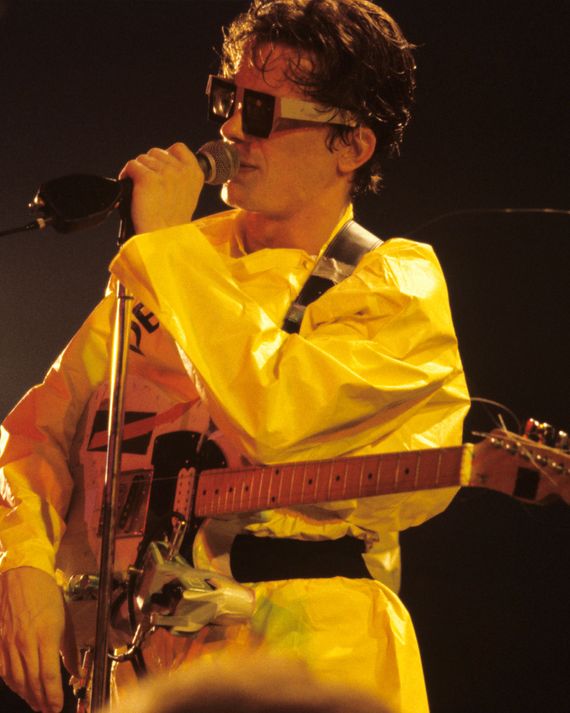

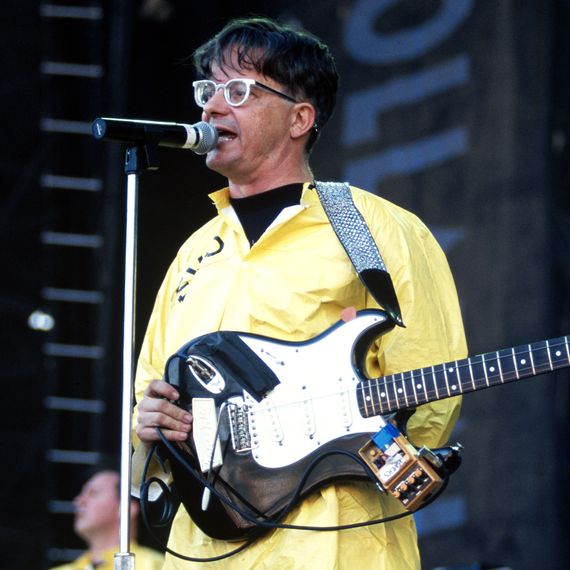

Suit with the most sentimental value

The yellow suits were hazardous-material outfits that you pulled over the top of your clothing. They were meant for people working in the rubber industry in Akron, and we were looking for something that wouldn’t be blue jeans or T-shirts. We wanted to do everything we could to make ourselves look not rock and roll. Jerry used to work at a janitorial company when we were starting out. We were always saying, “If we ever get money, we’re going to have all of these industrial things and prison toilets made out of stainless steel. We want lamps like the ones that are hanging in the warehouse at Coca-Cola Bottling Company.” We loved janitorial supplies, so when Jerry found that picture of the yellow suits, they were great. They were perfect for us because they were around $4 for a full suit at the time. We have to remake them ourselves now since the company stopped producing them a while ago. But at the time, we could just put four vinyl sticky letters on the shirt and the suit was done. I always loved that yellow suit. We could tear them apart! We’d always have black shorts and black shirts and knee socks underneath. It looked like we were on a ’50s high-school basketball team or something.

More From The Superlative Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music