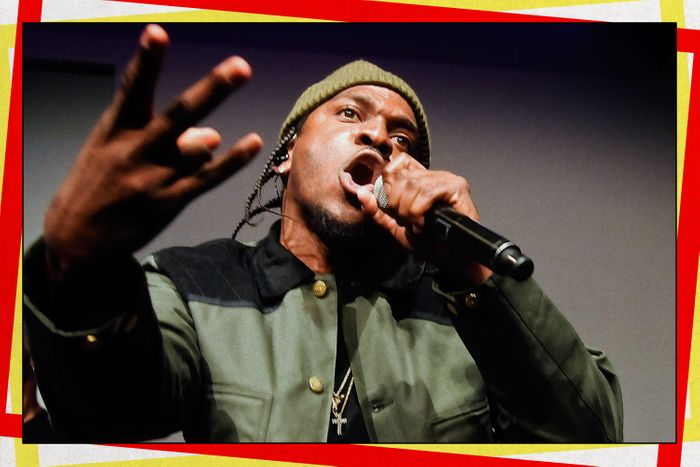

Pusha T in album mode is like a wrestler gearing up for the main event. You’re not only treated to a clinic from a technician at the peak of his powers — you also get to watch him cut diabolical promos about it. Few people on the planet are as confident about what they do as the rapper born Terrence Thornton. He’s earned it; the catalogue is tremendous. Rhyming with his brother, Malice, in the Virginia rap group Clipse, Push penned poisonous verses on 2002’s Lord Willin’ and 2006’s Hell Hath No Fury, both landmark drug-rap albums produced by the Neptunes. Together they stole everyone else’s thunder, hijacking popular beats of the era for the beloved We Got It 4 Cheap mixtape series. Over the past decade, working with Ye’s G.O.O.D. Music (first as a signed artist, later as its president), Push has proven his mettle as a solo rapper in a string of increasingly acclaimed works that balance a flair for timeless boom bap with a taste for offbeat rhythmic patterns. My Name Is My Name (2013) is as comfortable in the simple sample loops of “Nosetalgia” as it is in the jittery grooves of “Suicide” and “Numbers on the Boards,” and 2015’s King Push — Darkest Before Dawn: The Prelude made dominating subtly tricky beats look easy.

Four years out from impressing with Daytona — the seven-song wonder released during Ye’s hectic 2018 Wyoming sessions and a tense war of words with Drake — Pusha T picks things up with this month’s It’s Almost Dry, his fourth solo album. Its premise is simple: Ye produces six songs, and the other six go to Pharrell. Working with the defining producers of Pusha’s early career and his 2010s resurgence gives It’s Almost Dry a sense of balance and history. Because P and Ye are restless talents, auteurs who each developed a recognizable signature sound they’d just as soon ditch for a more unorthodox approach — and because Push excites his producers as much as they inspire him — It’s Almost Dry succeeds. Prior to the album’s release, Pusha walked us through the ins and outs of making music with the two mercurial hip-hop veterans and the lead-up to this moment.

.

Biggest difference between being produced by Ye and by Pharrell

Kanye and Pharrell love two very different things about me. Pharrell’s approach is a little bit harder for me to capture ’cause it deals in cadences and melodies and character. And Kanye just wants bars. He wants Re-Up Gang, mixtape Pusha: “Just give me all your raps and let me mold them into what I want to mold them into. And I’mma edit your shit, do a whole bunch of shit to your shit.” You got the best of both worlds on this one project.

Hardest part of clearing samples with a billionaire producer

If you know anything about working with Kanye, it’s that it’s a very, very, very tough, tedious, annoying process about the samples. I’ve never seen people take advantage of a situation like they do when it comes to clearing samples for this guy. I tried to hide the fact he’s involved. As soon as his name comes up, it’s time to take him to the cleaners. It’s the most unfair shit I’ve ever seen. It’s almost like they know he literally doesn’t give a fuck. He’ll be like, “Okay, well, great. They want 97 percent of the record. Give it to them! I want the record.” People come up with the most outlandish rates and numbers. It has to be a known thing throughout the industry. It has to be! He’s such a fucking artist. He just wants what he wants, and that’s it. The end-all, be-all is to get the song.

.

Favorite memory of making ‘Diet Coke’ with Ye

I look for what that beat reminds me of. What is the feel of that beat? I’ve been taught never to ignore my initial feelings when it comes to music. There’s always something there that made you bop a certain way, something that you might have said immediately. I’m an overthinker. I fuck that part up a lot. But I’ve been taught not to let go of that first flow. Let it out. That’s usually where the initial freestyle or the words that I’m playing with come from when I’m being produced produced. On It’s Almost Dry, it happened with both Pharrell and Kanye. We weren’t compromising with the bars. Ye was like, “I want a cadence every time.” It happened specifically on “Diet Coke.” I guess I was taking too long to write to it. He was like, “Nah, man, you not getting out of this one. You gotta do this,” and he just started mumbling [hums the “Diet Coke” flow] “Da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da, da.” He does his best mumble rendition of who he thinks I am. He goes through the beat like that. He was like, “This is the cadence. This is what you do. If you do that, sounding how you sound, and saying the shit you say, you’re going to love this song.”

As a rapper, I’ve always understood that it’s not just my bars that make this shit great — it’s how I marry the track. Production has always been a big part of my makeup. But I think rappers get in their own way, because when you rap really good, you think you can rap over anything ’cause it’s all about you. You have to be a bit more selfless. You’re not just doing this for you. You’re not just doing this for the best line. You’re doing this for the best line that marries the track that you’re on top of. Sometimes it’s not about how great that one lyric is but how greatly it can be mashed into that beat.

.

Lessons from witnessing the end of Ye and Kid Cudi

It fucking sucks. You know Cudi is my fucking brother to the end. Just navigating these relationships, this brotherhood, the arguing … it gets public. It’s one thing for us to argue. We all argue — that’s not a problem. It gets out there, whether it’s Ye bickering first, or Cudi coming back with what he says. It’s super–fucked up. The day we made this record, everybody was so fucking happy. Ye’s chopping the Beyoncé sample. Cudi happens to come in that day. We see each other, and I hadn’t seen him in a while. He’s like, “I gotta get on a record. Are you crazy?” Cudi did, like, three or four different references. Beyoncé cleared the sample. There was so much great energy around the making of that record. And, you know, time passes, and issues come up. Cudi really doubling down on this being the last time we’re going to hear them two together … He’s a super-convicted motherfucker. So I appreciate him clearing it up. He did what he did for his bro, and I love him for that.

.

Film that most inspired It’s Almost Dry

Pharrell really wanted a character for “Call My Bluff.” He was like, “I’m getting regular Pusha T; I need some character. You have to lay this differently.” We were watching Joker every day while creating the project. Pharrell was like, “Man, this is who you are anyway. You’re actually this guy.” That’s why you get that tone — me saying very eerie, evil, demonic things very, very matter-of-factly.

.

Best advice for making a career out of rapping about crime

There’s a way to articulate whatever you’re trying to get across, and there’s a way to be conscious about it when you relive it. For me, when people don’t give a fuck, I begin to question how authentic it is. Where I’m at right now in my career, I am trying to be the Martin Scorsese of street rap. There’s the actual, real place where some of this shit comes from, but there is also the fictional element. Just make sure you’re creating the greatest product ever, to get it out to people who love this shit. I’m trying to take street rap to a whole nother stratosphere. I checked off the boxes as far as success in regard to where you’ve seen me. You’ve seen Pusha T in places — and affiliated with songs — and campaigns that you may not think you’re supposed to see. My biggest goal is to see how far this can go. I have done all the realest shit a hip-hop artist can do. Now I’m trying to take people on a more creative journey and mix and match everything I have my finger on the pulse of out in the streets.

.

Favorite Martin Scorsese film

I want to say GoodFellas. It’s taste, how they carried themselves. As gangster and as vile as these motherfuckers were, everybody wanted to be those guys. Everybody. You could’ve been any one of them.

.

Best 2000s mixtapes you didn’t make

Lil Wayne’s Drought shit was definitely fire — no hate, no nothing. G-Unit was going crazy. But at no point did I ever feel like anybody had the bars of We Got It 4 Cheap. Serious. We Got It 4 Cheap Vol. 2 smoked everything. The fucking world was fearful of them bars.

.

The Clipse’s biggest impact on hip-hop

The Clipse has arguably two classic albums. We made our mark when it comes to street rap, when it comes to blog-level critiquing of raps, when it comes to a mixtape. We watched how the mixtape circuit went from me going to Virginia State picking tapes up from bootleggers to getting them on the internet with Clinton Sparks. The Clipse has been a part of all of those different waves in a very strong position. I don’t like to reminisce about too much, though. The past two offerings from me and my brother, being back on tracks together (“Punch Bowl” and “I Pray for You”), say a lot about where the Clipse could be at today and where the group could go. My brother could not not have been on Nigo’s album, right? That wasn’t even a hard ask. We started out with this shit. Then, of course, I get the little-brother pass: “Look, I want you on my album.” He can’t just tell me “no.” That’s how I position it: “I want a verse!” I think people hear these two songs and they’re like, Wait a minute — this is something that we miss.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From Superlatives

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music