I remember trying to figure out who Taylor Hawkins was in 1997, when it came to light that someone other than Dave Grohl would be drumming on Foo Fighters records. This was a big deal if you spent a good bit of that year blown away by the skittering hi-hats sustained through the sinewy kit work on “Everlong.” Grohl was my teenage drum idol. By the time I was 13, I’d committed every second of his performance on Nirvana’s Nevermind to memory, absent the ability to play the instrument. (There was a brief, disastrous stint in my high-school band years, in which I switched from clarinet to snare and struggled to nail basics like a drumroll.) Tracing the influences and offshoots of Nirvana through covers and session work expanded my horizons. I discovered the poet William Burroughs from buying The ‘Priest’ They Called Him, a piece from 1993 with Kurt Cobain on guitar. It was Cobain and Krist Novoselic’s contributions to Mark Lanegan’s 1990 album, The Winding Sheet, that led me to the late legend’s solo catalogue in the years before he snatched souls in Queens of the Stone Age.

The commitment to hearing every Nirvana-adjacent recording put me on to Hawkins’s first Foo Fighters recordings. He didn’t get integrated into new material until 1999’s There Is Nothing Left to Lose, but Hawkins sat in on the radio sessions from the spring of 1997 that yielded a series of great covers originally spread out across the singles from that year’s The Colour and the Shape (which would later settle into odds-and-ends collections like Medium Rare and 00979725). On “Requiem,” originally from post-punk legends Killing Joke’s 1980 self-titled album, Hawkins flexed his power and control. Covering “Baker Street,” ex–Stealers Wheel singer-songwriter Gerry Rafferty’s 1978 solo smash, the drummer slipped into the space between hip-hop and rock-and-roll syncopations, mimicking a quality that helped push Nevermind beyond traditional rock audiences earlier in the decade. If the Foo Fighters changed dramatically under the hood in those years, as drummer William Goldsmith left and guitarist Pat Smear stepped out to sow his musical oats not long after Hawkins stepped in, it was impossible to tell by listening to the records. Grohl and Hawkins split drum duties on There Is Nothing Left to Lose, and the subject of which drummer plays on which songs continues to mystify fans of the band. It’s definitely Hawkins showboating with lightning-fast hits in “Breakout”; “Aurora,” a slow-burning ballad with a rewarding climax, is not just a great early Hawkins performance but the one he claimed as his favorite Foo Fighters song.

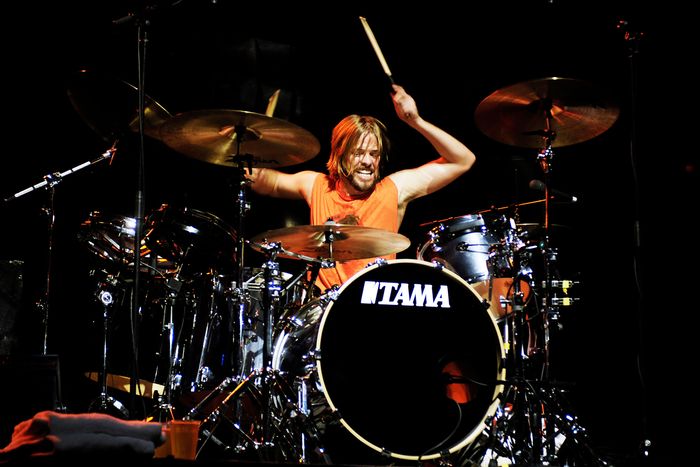

I found out about Hawkins’s death while attending a ’70s-themed party at a bar that played a lot of Queen. I thought about seeing the Foo Fighters at Madison Square Garden, where we were treated to a cover of “Under Pressure” with Grohl on drums and Hawkins on vocals, in 2018. It was Foo Fighters tradition to break up the set with a Queen tribute, in which Hawkins led a crowd-participation segment reminiscent of Freddie Mercury’s Live Aid vocal warm-up before singing a faithful cover. This portion of the show spoke to the kind of performer Hawkins was. His take on Mercury’s bombast got that theatricality and virtuosity can be delivered through a smirk. You didn’t expect the blond drummer in board shorts to be able to get around the jarring turns a serviceable Freddie Mercury cover entails, but he sold it every night with the same mix of self-effacing humor and reliable musicianship that informs the finest work of the Foo Fighters and much of Hawkins’s own work as the singer-songwriter in his band, the Coattail Riders. “Everlong” and “Learn to Fly” tug at your heartstrings as the videos tickle your funny bone, just as songs like “Way Down,” off Hawkins’s 2010 album, Red Light Fever, or “I Really Blew It,” from the 2019 follow-up, Get the Money, offset sincere emotional distress with knowing, ’70s party-rock pastiche. Hawkins had layers. An accomplished player, he wasn’t always the most confident. Naming that Coattail Riders album after “red-light fever,” studio musicians’ term for anxiety that sometimes appears when the red recording light goes on, is a clue. It’s worth noting that the reason Grohl and Hawkins split drum duties on There Is Nothing Left to Lose was to boost the drummer’s confidence by easing him into the process of making records. You’d think he wouldn’t be meek. He spent two years touring in Alanis Morissette’s band before joining the Foo Fighters. (If you caught the controversial HBO Max Jagged doc last year, you also saw him admit that the backstage antics on the tour ran counter to the message of the album, an ultrarare mea culpa about rock-and-roll recklessness.) The debut Foos single, “This Is a Call,” intrigued him, as he would explain in a 2019 Kerrang! Radio interview, because it sounded like “Steve Miller had Bad Brains as his backing band.” He didn’t come from a punk background, but he could appreciate the wires Grohl’s music was crossing. Joining the band meant jumping from sold-out stadium shows to smaller rock clubs, but toiling away on Lose earned the Foos its first Grammy and “Hot 100” hit.

When I spoke to Grohl last fall in advance of the Foo Fighters being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, I said the band seemed like an afterlife for the storied players in its ranks, a place for punk-rock veterans like Smear of the Germs and Chris Shiflett of No Use for a Name to connect to the international attention they deserve. “The whole idea with the Foo Fighters is to be a continuation of life,” Grohl explained. It echoed a point he articulated a decade ago in the career-spanning 2011 documentary Foo Fighters: Back and Forth: “We all entered into this new band like it was helping us get through the loss of the bands we’d been in before.” The Foos’ lineup was born out of the shattering of impactful alternative-rock institutions like Nirvana and Sunny Day Real Estate. It is, in many respects, a monument to carrying on. The enduring Foo Fighters singles — “Times Like These,” “Learn to Fly,” “Best of You,” “Everlong” — all talk about summoning the inner strength required to weather trying times. But it was a bit of an oversimplification of the story of the band to say it’s been the last of everyone’s struggle. Graduating to larger venues and gaining the respect of rock-and-roll legends and United States presidents meant an end to money troubles, but Hawkins admitted over the years to fighting to balance work with a taste for nightlife antics. A 2001 overdose after a summer festival gig in England left him in a coma. The band almost ended right there, as Grohl would later tell the Guardian: “When Taylor wound up in hospital I was ready to quit music.” Hawkins thankfully recovered. (His first words were “Fuck off.”) We’d also learn in Back and Forth that “On the Mend,” the tender song about rest in the acoustic half of 2005’s double album, In Your Honor, was written in response to the scare. “It’s sweet, I suppose,” Hawkins said in a 2011 Q magazine interview with the band, “but I could’ve gone my whole life without knowing it.” He didn’t want to be known for what he did in his worst moments, the subject of headlines about private darkness and tragedy. He would almost certainly hate to be the subject of rumors about which substances he used.

Death strips away our ability to control the narratives people accept about us, as they go looking for signs that it was imminent, when at the root of a terrible shock like this one is the inability to know it was going to happen. The Foo Fighters were loosening up. Last year, the band released its tenth album, Medicine at Midnight, its best full length in a decade, and the classic-rock obsessives in its membership started to lean into the Foos’ influences. Opener “Making a Fire” appears to ponder the question of what Soundgarden might sound like in the ’70s. (I was geeked to learn that Grohl and Hawkins grew a tight bond as bandmates in part from jamming together on Soundgarden riffs.) When Chris Cornell passed, Hawkins spoke out about seeing the grunge pioneer’s work as a nexus between prog rock, glam rock, and metal. With Medicine, it seemed like the Foos were interested in trying this blend out for themselves. You think “No Son of Mine” is going to be a cover of the tune from Genesis’s We Can’t Dance, but it’s more of a Motörhead tribute. Lead single “Shame Shame,” an excellent showcase for the more delicate side of the powerhouse drummer’s touch, feels indebted to the big riff in “Underture,” from the Who’s Tommy. This year, the Foo Fighters released Studio 666, a rock-and-roll horror-comedy in the spirit of classics of the form like Trick or Treat and Black Roses, in which ex-Slayer guitarist Kerry King is almost immediately burned to a crisp and Lionel Richie cusses Grohl out in the middle of a cover of “Hello.” Last month’s Dream Widow EP saw the band playing the part of the film’s ill-omened metal outfit, an excuse for the Foos to tap into doom, death, and black metal that landed like a sucker punch after last year’s batch of Bee Gees covers. The catalogue was starting to feel as loose and free as recent shows have been.

This was supposed to be an upbeat year for the Foo Fighters. My heart breaks for the band, for the families, and for everyone touched by Hawkins through work or personal acquaintance. His excitement about the whole of rock history was infectious, as you see in the Kerrang! Radio talk, in which he shows off rock memorabilia in his home studio and outlines the reciprocal relationship between British and American rock. Taylor Hawkins understood the mechanics and history of the genre and his place in it but also — and this is every bit as crucial — how to never let it go to his head. Tributes from everyone from Machine Gun Kelly to Paul McCartney paint the same picture: Hawkins was a one-in-a-million talent who made you feel like a million bucks.