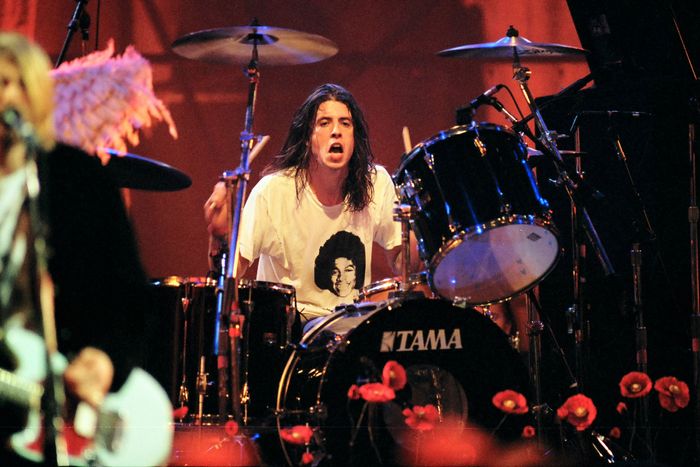

I meet Dave Grohl the day after a mid-September Foo Fighters gig that almost didn’t happen. A lingering fog had left the band’s private jets stranded on the JFK tarmac for almost four hours; Live Nation asked the members to record a video to play inside Syracuse’s St. Joseph’s Health Amphitheater, which seats more than 17,000, announcing the show had been canceled. Moments before Grohl made the call, he got the all clear from the pilot. Foo Fighters raced into St. Joe’s flanked by a police escort, opening with the triumphant “Times Like These.” Weather delays are no sweat for the rock lifer, whose path to arena-front-man status wove through Scream, the venerable D.C. punk outfit he left in 1990, to Nirvana, whose meteoric ascent ended abruptly with the death of Kurt Cobain four years later. Foo Fighters, a project that began as a batch of solo demos and ballooned into a brotherhood of punk and emo vets, will be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this weekend, making Dave a two-time honoree after Nirvana’s induction in 2014. Between the ceremony and the rollout of his new memoir, The Storyteller: Tales of Life and Music, Grohl is in the reflective mood.

It’s the fall of 1991. Nirvana is in the middle of a club tour when Nevermind is released. It sells a few thousand copies in the first few weeks. By the end of the year, it’s selling hundreds of thousands per week. At what point do you notice things have changed?

We were blissfully unaware of a lot of that because we were stuck in a van with a U-Haul trailer pulling up to little clubs and loading our own gear into the gig. I remember the night the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video debuted on MTV on 120 Minutes. Kurt and I used to share a room. We knew it was going to be on the show. That night, we realized we had gone from a band in a van with the U-Haul to a band in a van with the U-Haul on fucking TV. But we were moving so quickly at that point. I don’t think we realized what was happening until months later. The thing we did notice was the amount of people at the shows. We were booking places like the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C. It held 200 people. You would pull up to the gig and see there were more than 200 people in the club and more than 200 people outside trying to get in.

It’s so different now. People are really attuned to the numbers.

I don’t think any of us started playing music with a career in mind. You fall in love with the Beatles, and you pick up an old instrument, and it becomes this puzzle or this game. You find like-minded friends who are trapped by the same obsession. You start playing your own shitty songs in the basement. Maybe you do it in front of people and you start to crave this relationship with the audience. The other stuff, if it ever comes, comes much later. It’s a different world now. I do think as I watch my daughters learn to play music, they’re starting from the same place I did. The initial intention is genuine, and that never goes away.

In 1992, you released the Pocketwatch tape, your first solo project, under the pseudonym Late! When did you realize Kurt Cobain was aware of your side projects?

When I first joined the band, I played them some things I had recorded in Virginia in between Scream tours. So they knew I recorded things by myself, but they were these little sonic experiments. I was just smoking weed, and I didn’t have anything else to do. It goes back to the famous old joke: What’s the last thing the drummer said before he got kicked out of the band? “Guys, I have some songs I think we should play!” Recognizing Kurt’s brilliance as a songwriter, I wasn’t going to try to squeeze in there. I was like, I know what my role in this band is. I need to pound my drums and push these songs out into an audience like a steamroller.

I had a cassette. I played them for Kurt and bassist Krist Novoselic in the van one day. I went back to Virginia at some point and recorded some more shit with my friend Barrett Jones on his 8-track. My friend Jenny Toomey had a label. She heard one of the songs and said, “I’m doing a compilation. Do you want to put a song on there?” I did. And then I started trying to write songs. Before, they were just these fucking crazy punk-rock experiments. I recorded the songs “Floaty” and “Alone + Easy Target.” I was proud of them. I remember playing “Alone + Easy Target” for Kurt. He kissed me. In no way did I think, like, Okay, this is going to be on the next Nirvana record. I was flattered and heartened Kurt acknowledged me as someone who could write a song.

Do you wish when he heard those early songs that he had asked you to pitch in on writing for Nirvana?

No. With “Alone + Easy Target,” he liked the melody and the riff, but he didn’t like the lyrics and he didn’t want to ask me if he could change them. So we never used it. In the last session Nirvana did, we recorded a song called “You Know You’re Right.” We sat in the studio waiting for Kurt for a few days. In that time, I recorded “Exhausted,” which wound up on the first Foo Fighters record. Kurt liked that one, too. But no. I didn’t want to confuse his process.

After Nevermind, Nirvana joined with producer Steve Albini for In Utero. Compared with the previous record, it’s confrontational and abrasive. There was pressure from the label about sanding down rough edges. That had to be awkward for a band that never had to listen to outside input about its music.

As the drummer, I wasn’t necessarily included in any of these career decisions at that point. It wasn’t always “All for one, one for all.” By the time we were making In Utero, there was a lot of attention on what we would do next. That pressure was put on Kurt, and I’m sure it wasn’t easy for him to navigate that clearly. I was done with the drums in three fucking days, and I sat around watching the rest of it happen. When we returned with those mixes, someone at the record company said, “You’ve got to be joking.” And In Utero is … I don’t want to say it’s my favorite Nirvana record, but it’s definitely the most powerful to me.

It’s the one I come back to the most.

It’s a complicated record, but I’m glad the world got to hear it. I loved playing those songs live. I wish I still could. I’ve done it a few times. I’ve played “Heart-Shaped Box.”

You don’t rip into “Scentless Apprentice” every now and then?

I mean, I’m getting old, man. No. When I get together and jam with Foo Fighters guitarist Pat Smear and Krist, with Annie Clark or Beck, or with my daughter, and we play a song like “Heart-Shaped Box,” I beat the shit out of those drums twice as hard as I did fucking 30 years ago. I miss it.

Journalist Michael Azerrad wrote a piece recently with stories from his time around Nirvana, and one stuck out: He said there was a night during the American tour for In Utero when Kurt was yelling in his hotel room about firing you. He told Kurt it was perfectly plausible that you, being in the room next door, had heard him. I wondered if you did.

I hadn’t, and I have kind of a different version of that story. We were on our way to Los Angeles to start production rehearsals for the In Utero tour, and I was sitting a few rows ahead of Kurt and Krist. I could hear Kurt saying, “I think we need a drummer that’s more rudimental, along the lines of Dan Peters,” who was the guy they almost hired when I joined the band. I was really upset because I thought things were okay. I talked to Krist, and I said, “Is that really what you guys want to do? Because if that’s what you want, maybe just let me know, and we can call it a day.” I eventually talked to Kurt about it, and he said, “No. That’s not what we want to do.” I just felt like, It’s up to you guys what kind of drummer you really want, and they decided I should stay.

How close was the band to coming apart or being completely restructured?

Honestly, in that last year, you would wake up every day not knowing what was going to happen next. We were on shaky ground for a lot of reasons, the biggest being that the sudden rise to fame in that band was traumatic. I can’t speak for Kurt, and I don’t usually because he’s not around to speak for himself. Each of us dealt with it in different ways, but ultimately that’s a hard thing to navigate. We had shunned mainstream commercial appeal and were perfectly happy in our world behind the fucking shadows. Then we become one of them. How do you fucking process that? There was a lot of chaos within and outside the band. You had to hang on for dear life and hope the ride didn’t stop.

Do you ever struggle with what to keep to yourself with regard to Kurt — a friend who’s no longer with us, who made such an impact that people want to know every last detail?

Not at all. I’m selective in what I tell everybody. Here’s the thing: Nirvana were people. It’s hard to remember when it becomes a logo or a T-shirt. It was just three people who wound up writing songs, touring around in a van. When it comes to things that are deeply personal, I choose to share with the ones closest to me. If my daughters ask me questions about Nirvana, I will answer every one of those questions.

When you became a front man in your own band, did you start to see Kurt in a different light?

I learned a lot of lessons in Nirvana that I applied to being the singer of Foo Fighters, about what to do and what not to do. Publishing is a good example. We have a Bernie Sanders–style formula for publishing on every song. You don’t have to play on or write the song and you’ll still get publishing on it. It removes the conversation so you don’t wind up in any sort of inner conflict. The history of rock and roll is filled with that same old story over and over again. To me, the best idea was to nip it in the bud and have this formula for everything.

You haven’t had any major scandals in your career. How did you pull that off?

I’ll go back to when Kurt died. The next morning, I woke up and I realized he wasn’t coming back and I was lucky to have another day. I sat and made a cup of coffee. I can have a cup of coffee today. But he can’t. I got in my car to take a drive. Beautiful day. Sun’s out. I’m experiencing this. He can’t. It was then I realized no matter how good or bad a day, I wanted to be alive to experience it. That becomes your divining rod. I just want to get to tomorrow. I just want to fucking make it one more day. Especially in — I’m not going to say “in times like these.”

I feel like this is crucial to the songs of yours that have endured: “Times Like These” but I’m also thinking about “Everlong” and “My Hero.” The songs that go the distance are about picking it up and continuing on.

I can’t write a song about something that didn’t happen or something I didn’t feel. The concept of starting over is a recurring theme. I’ve been through it more than a few times in life. You hit a crossroads and you have to steer your path. When Foo Fighters were making The Colour and the Shape, I was going through so much fucking shit. I had nowhere to live. I was going through a divorce. Pat was fucking leaving the band. The drummer had fucking quit. I didn’t have any fucking money in my pocket. I’m sleeping in my friend’s back room. His dog was pissing on me every night in my bed. I was ready to snap. I had these journals; I would list each of these problems individually. I’d look at this list and think, Okay, if I think of all of these things at the same time, I will have a nervous breakdown. If I focus on one at a time, maybe I could solve these problems. Maybe I can make it through. So I try not to get overwhelmed by everything that’s going on. I hit things one at a time.

I’m sure you’ve heard it said a zillion times over the years that the first Foo Fighters album is kind of a George Harrison All Things Must Pass situation. The biggest band in the world shatters, and you land on your feet with a great album. Do you listen to that self-titled record much?

I listened to it not too long ago. Sonically, it’s a crazy record.

It doesn’t sound like much else from 1995.

Part of it has to do with the acoustic environment, and part of it has to do with the urgency. The studio is unlike any other studio I’ve ever been to in my life. It’s built into the side of a hill. It’s like a gigantic bunker. The live room, the tracking room, is all stone and marble. Most people would consider that too harsh of an acoustic environment. We had six days, and I had 14 songs. And there’s only one person playing this shit. So I could spend maybe two hours on a song. So I’d do the drum track in one take, then I’d run and do a guitar track, maybe double it, put bass on it, and put it to the side. So within like an hour and 15 minutes, I was done with the instrumental track. And I had to do, like, four a day. The intention wasn’t to make a record. It was just to fucking record these songs on a 24-track.

You have recorded in basements and garages, in professional and personal studios. As the guy who made Sound City, an entire documentary about how great of a sound this one studio offered, you seem like you’re on a quest to find the perfect room.

Well, of all the rooms I’ve recorded in, Sound City is as close as you’re going to get. The magic of that old warehouse in an industrial complex in Los Angeles. It’s indefinable. It makes no sense why the room sounds the way it does. It just does. It’s like the Bermuda Triangle of fucking studios.

In your memoir, you say you chose Sound City to record Nevermind in part because it had the advantage of being close enough to the Geffen Records offices for them to make sure you weren’t “pulling another great rock-and-roll swindle, à la the Sex Pistols (something we actually considered at one point).” Please talk about that point.

I think the record company wanted us to be close so they could keep an eye on us. Because we were nobody. They were going to hand us this big check … which wasn’t that big. It was, I don’t know, $35,000. Whatever it was, they’re going to hand us all this money and fucking cross their fingers and hope they got a record. When we were being courted by all these record companies, they would fly up to Seattle or fly up to Tacoma, take us to Benihana, flash a credit card, tell us they’re going to give us a million dollars, and then we would go back to this shitty little apartment where we barely had any money to eat. When a record company says, “We’ll give you a million dollars today,” what do you do? You say no. That’s the poison apple. Or you take it and pull a rock-and-roll swindle. We were very familiar with the Sex Pistols story. I think we did the right thing. We followed Sonic Youth’s path. We got Sonic Youth’s manager. We signed with the label they were on. They blazed the trail. They were the ones that made it safe for a band like us to get a record deal.

You spent the ’80s and ’90s trying to find a stable band situation. Scream busted up, followed by Nirvana. I almost see Foo Fighters as an afterlife for you. Has there been much turbulence?

You reach a point where you cannot break up. Stop playing for ten years, but don’t tell anybody you broke up. It’s like your grandparents getting a divorce. What the fuck you going to do that for? If you look at the foundations of this band, we were four people who came from bands that ended prematurely. Nate Mendel and William Goldsmith came from the band Sunny Day Real Estate, Seattle’s coolest band at the time. Their singer, Jeremy Enigk, found God, and the band shut down. I was considering starting this new band, but I didn’t know anybody. I had a mutual friend with Nate who said, “They’re breaking up, and they have a show this weekend.” I go down to see the show. I thought, They play good together. I’ll give them a tape. Maybe we’ll go jam. Which we did. Our first practice was in William Goldsmith’s basement of his parents’ house where he lived. We threw it together almost the same way you put a band together in high school.

Pat and I, coming from Nirvana — that was a really difficult transition to make because when Nirvana ended, I don’t think anybody wanted to make music ever again. Just the thought of sitting at a drum stool broke my heart without Kurt being there. I had a fucking dream about him again two nights ago. I have these recurring dreams about him. In the dreams, the band gets back together, and we do it again. It’s a trip. Krist and Pat and I have a different connection to those songs than anyone else. When we play them, it reminds us of how far away that time in our life is and how natural it feels to do again. The whole idea with the Foo Fighters was to be a continuation of life. When Kurt died, someone from this band called 7 Year Bitch sent me a card. It said, “I know you don’t feel like playing music now, but you will, and it will save your life.” They were right. It took a while to get there, but the Foo Fighters saved my life, still.

I was thinking about growing up listening to grunge and how it was an early and lingering education about death. We lost Kurt Cobain. We lost Layne Staley, Chris Cornell, Kristen Pfaff from Hole, Stefanie from 7 Year. Did you ever feel like the scene was haunted as it was happening?

No. I mean, coming from Washington, D.C., I had never experienced heroin. I’ve still never taken it. D.C. wasn’t really a heroin town. Seattle was a heroin capital. It’s a port to the east. This shit just comes in, and not to mention the environment where it’s gray and rainy for five months out of the year. The alcoholism rates are so high, and there’s a lot of drug use and heroin everywhere. I didn’t understand that when I first got there, and it wasn’t long before I realized that the city was a heroin capital. So, no. But I’ll tell you I’ve known a lot of those people, and over the years when we lose one, I’ll see their bandmates, and it breaks my heart. I went to Chris Cornell’s memorial, and I was standing there talking with some of the guys from Alice in Chains …

Who lost two of their members …

I would look at their bandmates and think, Oh, you got a long road ahead of you, man.

Fast-forward to the sessions for the second Foo Fighters album, The Colour and the Shape. When you rerecorded Goldsmith’s drums, he quit the band.

We started making the record in the fall of ’96. We booked a studio outside of Seattle called Bear Creek. We had a producer, Gil Norton. He’s English, famous for working on the Pixies’ records. We’d written some songs, and we were doing preproduction. I had never worked with Gil before, but it was soon clear he does not fuck around in the studio. He was a taskmaster, a whip-cracking, ass-kicking, do-it-50-times-to-get-it-right kind of producer. I was into it. But it was hard. As we were doing prepro, everybody snapped. I remember watching Nate after a rehearsal throw his bass in the fucking trash can. I could see that William was not used to getting worked this hard by the producer. I was doing vocal take after vocal take. I’m like, Fuck. I’m the worst fucking singer in the world. I could see it wearing on William.

So we took some time off for Christmas. I went back to Washington. I wrote two new songs: “Walking After You” and “Everlong.” I demoed them in about an hour. At this point, we’re up against a deadline, and we’ve moved to Los Angeles to finish the record. I come back with these two demos. With “Everlong,” Gil said, “I think we should rerecord this and make it great.” He said, “I think you should play the drums.” I’m like, “Fuck, man.” Meanwhile, William’s up in Seattle. We do it, and Gil’s like, “What about this other song?” I’m like, “Just the fast part on the song. All right.” I start redoing drums. I’m like, “Fuck, man. I got to call William and tell him we’re redoing some of the drums.” I should have called him sooner. By the time I called him, he was really upset, understandably so, and I regret doing that to some degree. I flew up to Seattle to talk to him about it. He said, “I’m quitting the band.” I’m like, “No, no, no, no. Stay in the band. Be the drummer. Play these songs, and we’ll push through this,” and he said no. I’ll never forget one of the things he said: “Actually, my friend offered me a job digging ditches.” I said, “Really? You know what? You should do that for a little while.” I used to dig ditches. I did fucking masonry when I was a kid in the Virginia summer heat. Go dig some ditches for a while, then you’ll want to be a drummer. So yeah, it kind of imploded. I begged him to stay; he refused to stay. That’s the bottom line.

Editor’s note: New York reached out to Goldsmith, who said in response: “Pat, Nate, and Dave went to L.A., and I was up in Seattle waiting for word to fly down to finish the record.” After receiving no word, he contacted management and asked them to book him a flight. That’s when he got a call from Dave, who asked him to not come down yet, he says, and informed him they were redoing the drums on a couple of songs. “I flew down to L.A. anyway,” Goldsmith says. When he got to L.A., he checked into the same hotel the rest of the band was staying at. “Nate met me in the lobby later that evening,” Goldsmith recalls, “and when I asked him what was going on with the retracking of a couple songs, Nate’s response was, ‘Is that what he told you? He’s retracking all of them.’

“We had tracked drums on the record for up to 13 hours a day for three straight weeks, in one case doing 96 takes on a single song. So the idea that I would throw it all away because Dave wanted to play drums on two songs is preposterous,” Goldsmith continues. It was “finding out that all the work I’d done was being disregarded that led to my decision to leave.” He says that Grohl did ask him to stay in the band, which “I couldn’t justify after all the work I put into the record was disregarded.” He adds, “I then made a joke saying ‘The world needs ditch-diggers too,’ which is a Caddyshack reference, but I guess he didn’t get it.”

Sunny Day Real Estate reunited and worked on a fifth album at your studio a few years ago. The album never materialized. Goldsmith came out and said you shoulder some responsibility for the album not coming together. He walked the statement back but still sort of implicated you, as the owner of the studio, in the sessions not working out.

You should ask his old best friend, Nate Mendel, about that because he was there during those fucking sessions and he knows exactly what happened.

Yeah, Nate said there was no truth to those remarks. I wanted to know what your feeling about all that was. You think he’s still upset after all these years?

I mean, they tried to make a record and they couldn’t make it. Have you heard that record?

We heard a song or two. “Lipton Witch” was all right.

Yeah. I mean, to be perfectly honest, I don’t give that shit any bandwidth. When it’s so devoid of any reality, I don’t even clock in. I’m just like, “Meh.”

Your memoir starts off detailing some of the toll that being a front man has taken on your body. Have you considered slowing down? Or is that what this year is? The plan was to do this quick, compact tour, but you’ve ended up doing arena dates with a lot of breathing room between them. Are you easing up or just playing a tricky year by ear?

When I broke my leg, I remember thinking it was a message from the universe telling me to chill the fuck out. You aren’t invincible. You are vulnerable and fragile. You need to slow down. I considered it and then I went on tour for 65 more shows in a fucking chair. I truly enjoy what I do, and I am creatively restless.

I saw you in Madison Square Garden in 2018. There was a precision, which I think is the hallmark of the Foo Fighters. It is certainly a drummer’s band in that respect. You made sure that nothing ever felt scripted, though. There was a freedom to it.

As far as pulling a band together and making sure the song is tight and powerful, we try to be as fucking good as we can. But musically we have a saying: If it gets any better, it’s going to get worse. We rehearse to a point. I don’t like rehearsing extended jam sections in the middle of songs. Fuck that. It’s going to happen when it happens. I don’t want to choreograph that. The thing that gets me to the next show is not knowing what’s going to happen next. Especially after 26 fucking years. Oh my God. There’s no way. Part of the intimacy of a large show is allowing the audience to not only participate but giving them a clear view of the people that are onstage. With that comes that loose vibe where me and Pat are fucking with each other onstage, or me and drummer Taylor Hawkins are wandering off into treacherous jam territory in a song where you’re like, “Get to the chorus, motherfuckers.”

Talk about trolling Westboro Baptist protesters at your shows off and on for a decade.

It’s just too easy. The reason they started picketing us was that we made a tour commercial once where all of us were taking a shower together. I guess that fucking sent their flares up, and they decided to come picket Foo Fighters gigs every time we’re in Kansas City. If they weren’t so brutally offensive, we wouldn’t care, but what they stand for is horrifying. When they show up at your doorstep, you have to push them back, and of course we do it in the way we always do it, which is either to Rickroll them or play a Bee Gees song or pull up on a flatbed truck and play for them. But I have to be honest. To see that much hatred in someone’s eyes as they’re looking you in the eyes and screaming, “Dave Grohl, you’re going to burn in fucking hell,” and they fucking mean it. It’s like, Wow. I’m just standing up there playing a Bee Gees song. That’s real hate.

You’re a self-taught guitarist and singer and drummer. I’m curious about transference between those skills. The other day, I was listening to Wasting Light, where you’re really shredding. Some of those riffs almost look like percussion patterns.

I have some wires crossed where I place things in my mind. So if I’m singing a vocal, the cadence of the vocal is going to be determined by a pattern that connects with another instrument. When I play guitar, I look at the low E string like it’s a kick drum. I look at the A string like it’s a snare drum. I look at the higher strings as they ring out like cymbals. So it’s all connected. I also think of composition and arrangement like wheels in a clock. It’s big and it’s turning, and then there’s another little one next to it going, and they all spin in unison. I remember the first time I realized that “Kashmir,” by Zeppelin, was two opposing time signatures. I’m like, “This is math. Wow.”

Does it bother you, as a Led Zeppelin superfan, to know how much they took from people like Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson, and that people sometimes had to sue for proper credit?

That’s somebody else’s lawsuit, not mine.

I’ll put it differently: When we talk about the architects of grunge, we are talking about the U-Men and we’re talking about the Melvins. We don’t talk about, say, Tina Bell. The story of rock and roll is limited to the people who get to do the telling. I’m curious how you, as someone who’s a documentarian in addition to being a musician, approach the issue.

When I did Sonic Highways and got to talk with Buddy Guy about his beginnings and his move to Chicago, he thanked me for putting the spotlight on the blues. He was afraid the blues someday might go away, and so he was kind of saying, “Just keep passing it on.” I’ve always been open about the music that’s influenced me, and I give much props to all the people that taught me how to fucking play my instruments. I’ve always loved the idea of these roots that grow into something that blossoms for years to come, or seeds that are planted for the next generation.

I thought about this as I rewatched the Buddy Guy episode recently. How, in your work in film and television, the intention might be to create a record of music history for future generations.

I fucking interviewed a hundred people for that series. It’s a history of American music — not the whole story, but it’s a big part of it. I often wonder, “Is that my next book? Is that my podcast?” Because it needs to be heard so people will not only appreciate where we’ve been, but have something to look forward to. I do believe in the lineage of music. The evolution of American music, the evolution of instrumentation and technology and creativity. The purpose of life is to grow. I still believe this fucking crazy world of music we live in now is a community. If I’m standing onstage and there’s a K-pop band to my right and Alicia Keys to my left, we’re all in this together. The Foo Fighters might be, like, the Crosby, Stills & Nash at this fucking point, but we’re in this together.

Years ago, I was hell-bent on starting my own network. I was out of my fucking mind. “I’m going to start my own music channel.” I had this idea that music programming shouldn’t just be videos. It should be something that introduces the artist with more depth or substance, whether it’s live performance or mini-documentary. I got together with my old friend, Judy McGrath, who used to run MTV a long time ago. We sat down for dinner and she was like, “I can get you a channel.” I’m like, “Really?” “Yes.” Then she was like, “You really want to be a TV executive?” I was like, “No, fuck that. No way. No fuckin’ way.”

When you see veterans like Eric Clapton and Van Morrison loudly fighting the wrong battles and losing the plot, do you worry about how easy it is to lose touch? What keeps you on the pulse?

Today I was talking to my mother about how I’m so out of touch with the pulse of the culture. I said, “Hey, did you watch the Emmys?” She goes, “Yeah.” I said, “How was it?” She goes, “It’s fun to see what the people wore, but I haven’t watched any of the shows.” Then I realized I haven’t watched television in like five fucking years. Even if I were to watch a show, I’d have no fucking clue what’s going on. My memory’s full. You wake up in the morning, you put your shoes on, and you try to fucking walk a straight line. That’s it.

Over the past year, your fellow double Rock Hall inductees Stevie Nicks and Neil Young have sold part or all of the publishing rights to their catalogues.

Oh, we pay attention. I know everybody that sold their fucking publishing rights.

Have you thought about it much? Would you ever consider it?

I understand why some bands would. A younger band faced with the shutdown of a pandemic who might not be able to make their way through the other side — maybe that’s a reason. Maybe you’re at a point in your career where you don’t want to hit the road and play all the stadiums and arenas anymore, and you want to ride off into the sunset. Maybe that’s a reason. I haven’t considered it because we’re still making records and writing songs. I’m sure I’ll get there someday, where I’ll be like, “Fuck touring. Just take it, man. I’ll sell it to you. Give me a fucking number.”

How did you feel last summer when Krist Novoselic complimented a Trump speech and then had to backtrack and explain that, in fact, he’s not pro-fascist?

I can definitely tell you that Krist is not pro-fascist. Krist is one of the most compassionate, loving, and smart people that I know. I can assure you that Novoselic is not a Trump lover.

In February, you expressed interest in reuniting Them Crooked Vultures for another album. Have you been following Josh Homme’s child-abuse allegations this month?

I can’t talk about that, brother. I’m sorry. I can’t talk about that. That’s a hard “no” right there.

Would you cut your hair again?

Abso-fucking-lutely. I want to. My kids are like, “Dad, don’t. You’re too ugly. Do not cut your fucking hair.” I had this routine where I’d shave it with a

No. 7, and then I’d let it grow out. But I eventually stopped.

Which is your favorite Grammy?

Oh, come on. That’s like picking a child. I’d probably have to say the one that me, Novoselic, and Pat won with Paul McCartney for “Cut Me Some Slack.” Three of my favorite people all together won one Grammy, that was pretty cool.

How do you feel about the state of modern rock music?

I’m not sure what “modern rock” means, but there are some artists I really enjoy, young and old, that are making fucking cool music. When I listen to a Mitski record, I’m like, “This blows my mind.” There are things that I like, and then there’s things that I become obsessed with, Mitski being one of them. Or the Bird and the Bee. I mean, you wouldn’t consider the Bird and the Bee to be a modern-rock band, but oh my God. I think they’re the best band in the world. That’s our producer, Greg Kurstin. It’s Greg and Inara, and they write songs nobody else could possibly write. The Japanese punk-rock band Otoboke Beaver. Watch this video for a song called “Don’t Light My Fire.” It’ll blow your mind, dude. It’s the most fucking intense shit you’ve ever seen. So of course it’s out there. Is it going to be center stage at the Grammys next year? Who fucking cares? I’m watching someone like my daughter Violet discover it every day, and so to me, she’s where it’s at.

I think that you’re trying to integrate work and family more boldly than a lot of your peers are. I know your mom’s name and your kid’s name from projects you’ve worked on with them. I didn’t realize you and Violet’s cover of X’s “Nausea” in the What Drives Us credits wasn’t the original.

I have a funny connection with X in that I’m related to the drummer. And I didn’t realize this until the ’90s. I grew up listening to X. They came through Ohio, where my grandmother used to live. Her family is from Ohio. In the local newspaper, it said, “Los Angeles punk legends X, playing in Ohio.” It listed their names. The drummer’s name was D.J. Bonebrake. They all had punk-rock names. John Doe, Billy Zoom, Exene, D.J. Bonebrake. I had the records. She cuts out the clipping, sends it to me. She underlines D.J. Bonebrake’s name and says, “You might be related to this boy.” Then it clicked: My fucking grandmother’s maiden name is Bonebrake. That’s his real name.

The Bonebrake family came over to America before the American Revolution, from Switzerland through Germany and then to America. They settled in the Pennsylvania-Ohio region. They were Mennonite. They were like fucking Pennsylvania Dutch, horses and flat hats and shit. I finally got to meet him, and it turns out we’re actually fucking related to each other. But anyway, yes. So when I recorded that cover with Violet, I thought, Okay, she’s going to love this. She bounces back and forth from Joni Mitchell to the Misfits to X to Stevie Wonder to some random Russian techno-goth shit. She’s the best college DJ you’ve ever heard in your fucking life.

The gentleman from the cover of Nevermind recently came forward with a lawsuit alleging that it is child pornography. What’s your stance on that?

I don’t know that I can speak on it because I haven’t spent too much time thinking about it. I feel the same way most people do in that I have to disagree. That’s all I’ll say.

I can think of, like, four times that he re-created that photo. If it’s a problem, why keep revisiting it every five years?

Listen, he’s got a Nevermind tattoo. I don’t.

Solve a long-term mystery for me: Why would Kurt sometimes change the lyric in “Smells Like Teen Spirit” from “our little group” to “our little tribe”?

I don’t know. I was just trying to play the drums, man. Come on. I was just trying to get through the show!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’