In the late ’90s, north of Central Park but south of the Heights, your local celebrities were Cam’ron, Big L, and Ma$e. By hook or by crook, certainly by force of personality and not a wealth of resources, each one clawed his way to renown, carrying with him the language and character and history of the neighborhood. The cockiness, silver-tongued persuasiveness, and flair for flashy, matchy gear they flaunted in records, videos, and performances ushered the local culture into the national consciousness. And in the peaks and valleys of their careers, you began to see your ceiling, your floor. Their art memorialized your lore. When rappers come from where you come from, they loom large as examples, their paths forming a playbook of possible futures. Growing up watching any brilliant local, you became preternaturally aware of how good and how awful a person’s luck can be, how easily things can come together in your favor but also how quickly a good set of circumstances can disintegrate. Big L’s untimely death plucked an already legendary figure out of what ought to have been a meteoric career, leaving behind questions about what might’ve become of a rhymer who could go bar for bar with Jay-Z. Ma$e’s parade of platinum-certified singles ended with a surprise retirement and a lengthy stint as an Atlanta pastor, a pivot remembered now as a cautionary tale: “Don’t leave while you’re hot — that’s how Ma$e screwed up,” Ye famously warns in “Devil in a New Dress.”

Following Cam’ron’s journey, you learned that family, comfort, and self-respect are every bit as important to the Harlem veteran as a hit single. He made great records with his peers, particularly in those too-short Roc-A-Fella Records years. Sometimes, the new album got stymied by baffling delays — like the triumphant Purple Haze, which was released in late 2004 but promised a year prior — or by unexpected disappearances, like 2009’s Crime Pays, which arrived after a yearslong hiatus the rapper would later attribute to helping his mother recover from a series of strokes in Florida. His crew, the Diplomats, has incredible chemistry between Jim Jones’s rare blend of street bona fides and pop smarts, the relatability of Juelz Santana, and a colorful cast of characters including Freekey Zekey and Un Kasa. But the bustling collective doesn’t always get along or move in unison. Its many moving parts can also undercut a sense of focus, a reality borne out painstakingly loudly last year in its Verzuz battle with the L.O.X. (which, in the northern parts of the city where Jadakiss gets as much consistent and enduring play as Cam, felt like watching family members argue, knowing exactly how their skill sets will jibe). When it worked, it worked, and when it didn’t, Cam was doing whatever the hell he wanted to do, buying buildings or making movies or embarrassing conservative political broadcasters on their own shows. It will never be as appreciated as the sea change his pink polos and nursery-rhyme cadences were in the early aughts, but it feels notable for a guy who walked away from a Roc-A-Fella–Def Jam deal at the peak of his post-Haze pen game, feeling as if he wasn’t a big priority there, not to chafe about the what-ifs of that career forever.

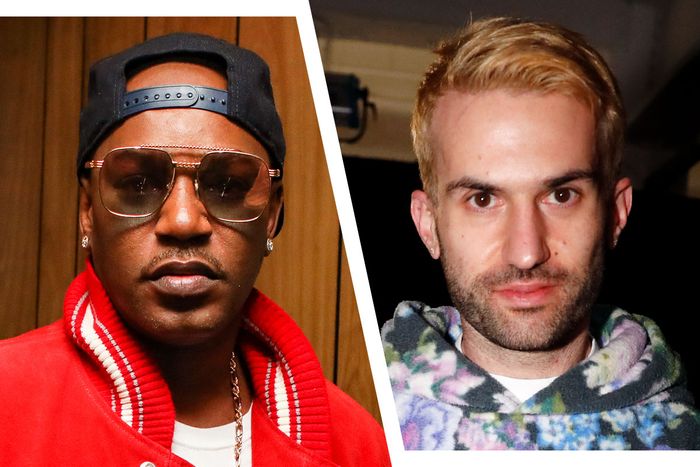

On this week’s U Wasn’t There, the collaborative album with DJ and producer A-Trak first previewed most of a decade ago, the Harlem elder walks us through the many phases of his life from childhood poverty and pro-basketball prospects in high school to stickups and pink trucks. Cam is unafraid to touch on points of controversy but disinterested in dwelling on them as he reminisces about early successes and local tragedies. He’s outlining the precariousness of the climb. The brushes with danger make the wins feel all the more miraculous, drawing contrasts between the rapper’s current financial stability and the years when the big paydays came from hitting licks. U Wasn’t There most resembles a Tony Soprano therapy session in that we’re watching a tough guy learn to relax and ponder romantic pursuits in the same gruff tones he reserves for his war stories. It’s a tricky balance, one that trips rappers up late in their careers. It’s hard to sound hungry when you have property and savings to fall back on, to talk too tough when the adversaries keeping you up at night are business rivals, not crafty neighborhood enemies. But these aren’t the issues that have held recent Cam releases back. There are brilliant songs on every project — “Golden Friends,” off the 2013 mixtape Ghetto Heaven Vol. 1, paired gruff double-time rhymes with a sample of the theme song from The Golden Girls, and 2019’s Purple Haze 2 features gems such as “Keep Rising,” with its great verse set to the Mary Jane Girls’ “All Night Long,” a Harlem cookout and block-party staple since the Ed Koch years — but Cam occasionally struggles with beat selection and quality control. A-Trak seems to have lit a fire under the guy, or else he hung back, compiling the best of the best.

U Wasn’t There catches the rapper in a unique space, free from a protracted cold war with Jay-Z over the acrimonious ending of their Roc partnership but also single and returning to the dating circuit after leaving JuJu, the longtime girlfriend and sometime fiancée he broke up with in 2017. The juxtaposition of the dire daily concerns of his robbery days and the quirks of trying to meet someone when you’ve been off the market most of the 21st century is hilarious. A lesser writer might struggle with that balance, but the rapper who made “Hey Ma” is in his element, telling lurid stories about dates gone comically wrong and reminding you how outrageous it is that he lived to tell his story. The first cut, a remix of Purple Haze 2’s “This Is My City” that trades the sedate pianos of the original for a roaring chipmunk gospel arrangement, leads with death and destruction, revisiting the mystery of the murder of Big L in the first verse, framing U Wasn’t There’s luxurious expenditures as comforts he’ll never take for granted: “Outside, more gunshots than Commando / That’s why I had to treat myself to Porsches, Lambos.” “All I Really Wanted” revisits the career windfalls of Cam’s young years in a few vivid lines: “In high school, I was on the court getting buckets, swish / Then I started getting duckets, can’t lie, I’m in love with this / The art of getting money, man, my motto was like ‘Fuck a bitch’ / By time I turned 30, I completed my own bucket list.” Each song imparts a bit of wizened advice or a diabolical taunt or a memory of a lost friend. Each verse is a hail of dazzling internal rhymes.

The wordplay here is potent, as jarring in an intricate story song as it is in a flurry of random insults. Nodding to “Gone,” the classic Cam and Kanye West collab from Late Registration, U Wasn’t There’s “Dipset Acrylics” spins a familiar punch line into a string of lines wilder than the Late Reg verse: “You superficial, I’m super-official / Coupe to coupe, still I be on the stoop with a pistol / And I got it, who need meth, I’m still moving the crystal.” “Cheers” takes us back in time with the first verse — “Fisticuffs had my wrist in cuffs / Roaches, mice, rats; in fact, they all lived with us / Got an opportunity, Killa, he wasn’t slipping up / Had cokeheads like the K9 unit, yeah, they would sniff it up” — and then drops us into a bit of frivolous Instagram drama in a second verse that feels like a backdoor pilot to a sidesplitting reality show: “Call me a perv / Text like she writing a scripture, swerve / Ask why I’m liking her pictures, the nerve / I liked the picture ’cause I liked the picture / Now curve, heart-eye emojis, ‘You real exciting, nigga’ / Absurd.” He leaves us with a couplet that could work as a dating-app bio or an assessment of having seen so much that social-media smoke barely registers: “Low key, static free, ’cause Cam is cozy / You nosy, I ain’t beefing over no damn emoji.” “Ghetto Prophets” is full of rude boasts: “She about a 7 so I took her to a four-star,” “In the glove, I got the semi cocked / Don’t talk old money if you never had a Benzi box.” The batting average is astounding. He is hitting all his marks, rhyming so hard that guest appearances from storied New York rappers such as Styles P and Conway the Machine feel like pleasant detours from the virtuosic show the main artist is putting on.

A-Trak is a good foil for a project like this. It feels like someone is finally imposing on Cam’ron a sense of what the public wants from him; his half-dozen tapes with Vado are proof he works with people he likes and not just people he thinks will advance his career and bolster his record sales, as mainstream rappers often must. (“Cheers” seems to cover his preference for creative control, and his reluctance to bow to trends, in just a handful of words: “Rather distribute, couldn’t go the consumer route.”) The beats — co-produced by everyone from Texas cloud-rap impresario Beautiful Lou to Eminem collaborator DJ Khalil to veteran New Jersey beat-maker !llmind — play with the building blocks of the rapper’s classic singles without descending into self-parody. The shouting choirs of “This Is My City” evoke the hard-hitting soul chop from Dipset’s “I Really Mean It.” U Wasn’t There wraps its arms around soul, rock, gospel, and reggae without losing sight of a specific sense of time and place, a suitable fit for a rapper who could rep the neighborhood in any genre setting, who skated across Sting’s “Fragile” on his first album and spit a few of his coldest bars ever over the Hill Street Blues theme song on his best album.

Brevity keeps the mood of the album and the quality of the songs consistent. There’s barely room for filler. You could argue that U Wasn’t There might even be too short. We’ve heard three of its nine songs in some form over the past eight years. (In 2014, the bonus cut “Dipshits” was a tantalizing teaser. That year, the album was announced under the name Federal Reserve, which is the subtitle of the new version of “This Is My City.” How many versions of this album exist?) But it is precisely this curatorial eye that makes the curt and concise U Wasn’t There feel like one of the best Cam releases in recent memory. It benefits greatly from a shared vision, from a brain trust of executive producers including A-Trak and his brother, Dave 1 from Chromeo, as well as Roc co-founder Dame Dash, a quick-tongued Harlem legend in his own right (pause). Dame’s two-minute “Dame Skit” interlude is every bit as potent as the raps situated on either side: “I asked him if he was copping a new house. He said don’t disrespect him. He just copped ten acres. I said, ‘You right, we only get neighborhoods, compounds.’” Dame delivers the album’s thesis before he goes, “Twenty or 30 years ago, we were sitting around talking about what we was gonna do, and we did it. We had dreams, and we made ’em come true.” Elsewhere, in “Dipset Acrylics,” Cam can’t help but phrase this notion as a snap: “I stay inside a new something / Your dreams still alive ’cause you keep hitting the ‘Snooze’ button, you fronting.”