Felix Gonzalez-Torres did it live. Instead of keeping a studio — he said that was for artists who needed to “rehearse” — he often wanted to find out what his ideas for billboards, light strings, and candy piles would look like at the same time everyone else did: while they were being installed. “When you don’t have a studio, you take risks, you change your underwear in public,” he told an interviewer in 1993. “I’m not afraid of making mistakes; I’m afraid of keeping them.”

He died of AIDS three years later, at 38, and the thing about dying young and famous is that everything you did gets kept. Drafts become archive. Mistakes turn oeuvre. This month, power gallery David Zwirner filled its wide, multi-address building on West 19th Street with a show dedicated to four of the artist’s monumental installations, including two never manifested during his lifetime. Gonzalez-Torres is often called a conceptual artist, meaning a lot of his work takes the shape of an idea; because the art market runs on fairy-dust, magic-bean logic, these ideas can be bought and sold even if they’re not carried out. At Zwirner, the never-before-seen works bookend the space: In a stark room at one end, there’s “Untitled” (Sagitario) (1994–95), a pair of perfectly round, filled-to-the-brim reflecting pools sunk into the gallery’s concrete floor, close together enough that a breeze generated by the sweep of an overcoat could blow water from one to the other. At the other end, there’s “Untitled” (1994–95), a pair of massive billboards mounted in the center of a room and facing in opposite directions. The overhead light suddenly drops to black to a soundtrack of loud and startling applause.

The artist expressed these ideas as specs for installations in terms both particular and vague. A billboard should just be made like a billboard, whatever that means where you happen to be, as long as it uses the image or words he specified. Andrea Rosen — who was his art dealer when he died and whose gallery now co-represents his estate with Zwirner — said Gonzalez-Torres’s plans for the pools were simple: They should be 12 feet wide, the water level with the floor. “Someone might choose to paint the inside blue,” Rosen said, “but those things are irrelevant. Felix worked hard to get to an essence. It’s a pared-down ‘This is the intention.’”

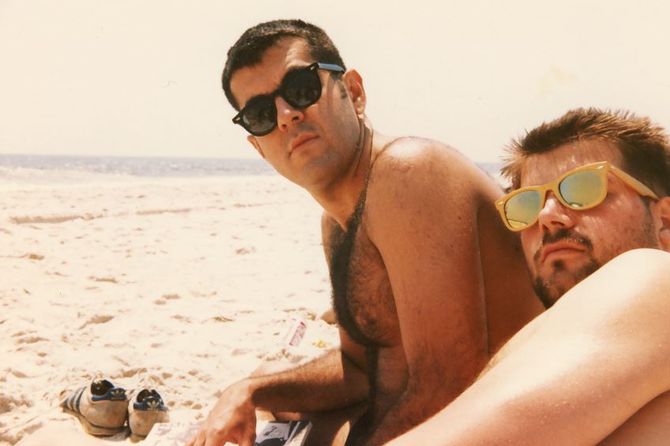

But what was that intention? Gonzalez-Torres never said, and he was famously slippery. He insisted his work was personal but rejected the notion that he was the only one who could give it physical form. While he always used objects, the objects might be disposable. Sometimes he enjoyed the idea of being a threat to the market; other times he wanted to use it. And he saw evasion as his superpower: In an era when conservatives were attacking the work of gay artists, he made art inspired by his boyfriend’s death from AIDS and dared any theoretical homophobe to find obscenity in a pair of clocks — “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) (1987–90) — merely ticking along together, until eventually, inevitably, one slows first and stops, at which point both clocks are reset. As he told one interviewer, “If I were to do a performance with HIV blood … that’s what the rags expect because they can sensationalize that.”

“The absence of information creates responsibility for the borrower, the curator, the owner,” said Rosen. “This is a piece that will be made over and over, and each time someone may make different decisions.” (Rosen said both works had been owned by someone after Gonzalez-Torres’s death, but she would not confirm if or when they were sold: “They were not sold in his lifetime. They have an owner.”) Fans of the artist haven’t always been happy with her choices — as in May 2020, when Rosen and Zwirner invited 1,000 people around the world to stage their own version of the artist’s AIDS-inspired 1990 work “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner) with a suggestion to tag it on social media. Collectors and dealers ordered hundreds of fortune cookies, piled them in the corners of their chicly appointed pandemic nests, and dutifully posted. Many critics were infuriated, calling the result indulgent and out of touch. (It didn’t help that it went live the same day Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd.) A Los Angeles Times art columnist who had been invited to participate declined, calling the project “Felix Gonzalez-Torres as Instagram prop for the art-world well connected.”

Then, a few months ago, there was a kerfuffle in Chicago when disgruntled visitors to the Art Institute thought the museum had intentionally edited the wall label for Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 piece “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) to avoid directly mentioning his longtime partner, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS the year he made it. (This was still the focus of the audio guide, and the museum has since changed the label.) Rosen, who seemed frustrated by the issue, declined to discuss it on the record. When I asked about the fortune cookies, she pointed out that they had invited people from outside the art world, too. “I think anyone who chose to be part of the project thought it was very meaningful,” she said. “But everyone has the right to think what they want.”

Some may see the interpretations Zwirner proposes for this show as an attempt to make up for past controversies. The press release suggests multiple meanings for “Untitled” (Sagitario): Perhaps the pools evoke “themes of the poignance of partnership, relationality, and queer intimacy.” Perhaps “the exchange of fluids between two human bodies.” There’s no text provided near the pools themselves. When I entered the room, the water seemed frozen, perfectly still. Only when I crouched down could I see ripples whiffling along its surface, the dust motes on the top. Liquid is meant to leak across the concrete; from where I was standing, the ground between the pools looked dry. With no artist, no context, no perceptible exchange, maybe the work remains just an idea.