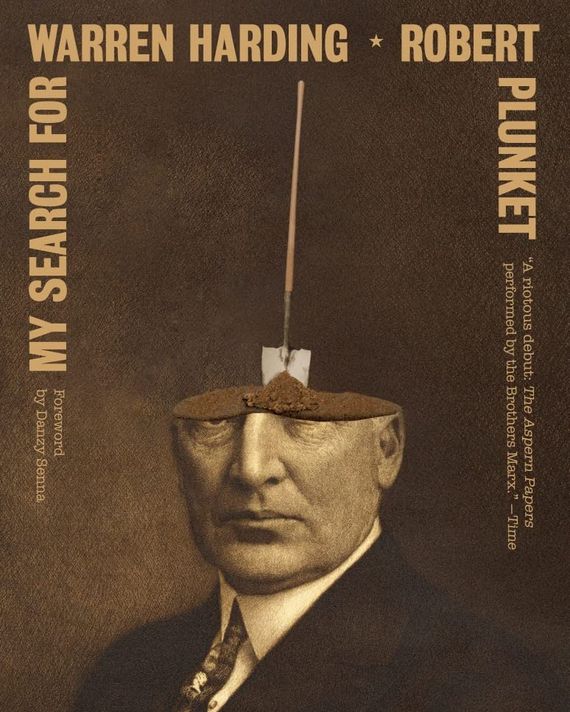

Robert Plunket is finally getting his due. My Search for Warren Harding, his first novel, published in 1983, was reissued in June by New Directions, prompting a round of praise for the author from all corners: the New York Times (“stealthily influential”), The Paris Review (“one of the best, and most invigorating books I’d read in years”), and The New Yorker (“one of America’s funniest, gayest writers”).

So where has Plunket been this whole time? After a sojourn in the downtown New York theater scene as a young man, the now-78-year-old Plunket moved to Florida in the 1980s, where, until about a year ago, he wrote the “Mr. Chatterbox” gossip column for Sarasota magazine. He’s had a wide-ranging career, reporting on the gilt and drama of the Gulf Coast, acting off-off-Broadway, appearing in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, publishing novels, and joining the White House press corps in Florida on 9/11. And now he’s retired. “I want my fans to know that I have found peace and contentment at a lovely trailer park in Florida,” he says.

My Search for Warren Harding finds a catty, cutthroat, embittered, insecure East Coast presidential historian in Los Angeles in search of love letters exchanged between Warren Harding and a (fictional) mistress, Rebekah Kinney, now an old woman living in a Norma Desmond–y mansion in the hills. The historian, Elliot Weiner, is obsessed with recovering the gleaming Hardingiana he thinks Rebekah has, convinced it’ll be a boon for his career. As he schemes and hurtles around L.A., Elliot spends most of his time tossing off callous, culturally tuned observations that cohere into a cheeky, contemptuous, self-satisfied queer sensibility: “By now, I was at the bottom of the stairway. I strained to listen. But the acoustics of the Hollywood Hills are notorious for their unpredictability. A case in point: Sharon Tate, et al.”

Arranging to speak in early July, Plunket told me he could talk after he finished body-surfing off the coast of South Carolina. When we got on the phone, we discussed Floridian scandals, contemporary fiction, U.S. political history, and Juicy Couture.

How was surfing?

It was too hot to go surfing! Literally, I go outdoors and have to come back in. I’m no spring chicken, and I’ve got to be careful.

What are you doing instead?

At the moment I’m staying with some friends, and we’re sitting indoors and we’re telling each other jokes and things like that. It’s holiday weekend kind of stuff.

How long have you lived in Florida? And how long did you write your “Mr. Chatterbox” column for Sarasota magazine?

Forty years and 40 years. I just retired about a year ago.

Is there a lot of drama in Sarasota?

Oh, there is! It’s a funny kind of drama. I don’t know if you’ve ever lived in a small town, but a small town has just as much drama as a big town. But it’s even better because you know the people involved. When there’s a scandal, you always know somebody. I remember when the sculptor John Chamberlain, who did crashed-automobile sculptures — somebody broke into his studio, and it turned out that I not only knew him, I knew the guy who broke into his studio. So when something interesting, scandalous, disastrous, embarrassing happens, you get to see it firsthand and up close. And it’s fascinating!

What’s the messiest drama you ever observed in Sarasota?

The messiest was the 2000 election, Gore versus Bush. But Pee-wee Herman was … I don’t want to say exciting, but kind of tragic also — the guy who owned the adult theater where Pee-wee was arrested was a very good friend of mine, so I was also in the middle of that one. That’s what makes being a small-town gossip columnist so much fun.

Were there certain themes that cropped up time and again?

Sex is always there. Greed is always there: trying to make money and maybe doing something that’s a tiny bit illegal and sometimes a tremendous amount illegal. One of the best things about Sarasota is that it has a history of attracting these people who come into town, and they have a lot of money, and they buy a big house, and they give to the right charities and become prominent in society and then something from their past shows up and they end up in ruins. It happens over and over again. It’s the oldest story in Florida. We had a mini Madoff scandal — a guy who embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars in a Ponzi scheme.

Part of what feels so notable about your writing is that it expresses a gay or queer sensibility through a lot of different, complementary emotional registers. My Search for Warren Harding is funny, energetic, and bitchy, but it’s also a complicated character study. Which, to me, feels different from a lot of popular gay fiction today. I wonder if you feel that way too.

Well … absolutely. But I didn’t write it as a gay novel. I did and I didn’t. It works both ways. If you’re alert to the homosexuality, the extremely repressed homosexuality, then you get it. But, particularly when it first came out, most people missed that, and they saw this mean, spiteful, pompous jerk being a fool, not realizing the whole secret to it was the repressed homosexuality that he couldn’t deal with. So, yeah, from that point of view, it’s much, much different from most gay novels.

I guess I’m thinking of a certain type of novel that exists today that very somberly reflects on trauma, and the characters cry during sex and that sort of thing, and there’s not much irony to speak of. This is so different from that.

I know, and I think I lucked into my point of view. And, of course, one of the reasons I could do it was because I wasn’t trying to write a gay novel with a sympathetic gay character. I was writing a character who happened to be gay, and that was the key to his character. Can you think of any novels that fit into that category at all? I really can’t. I’m sure there must be some. They always end up a little earnest, a little sincere, and “We’re proud to be gay,” or they find themselves and accept themselves, and that doesn’t happen with Elliot Weiner. I’m part of a much older gay generation, much more closeted, and with good reason — you kind of had to be to get anywhere in the world. And this reflects that way of thinking, that way you had to live … but there’s still a lot of gay men who for some reason or other have ended up in a corner where they can’t deal with it.

That feels so much more honest to me, stacking repression on top of humor on top of x, y, and z.

Do you read a lot of gay novels?

I guess so. They’re all sort of mixed in with everything else. But I don’t really like the weepy type I just mentioned. Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is maybe the most emblematic mainstream example of that.

I’m not familiar with that one.

So you’re currently working on a novel set during the Civil War. What draws you to American political history as a subject?

The hypocrisy of it, and the fact that there’s so much hidden between the lines of history that you can explore fictionally but can’t explore historically — because a lot of it is legend, folklore, and gossip. This thing I’m working on now is about the Confederacy. It has a lot of gay characters. It’s hinted at if you read it historically, but then you have to fill in all the blanks and make up the story of what it was like before the modern idea of being gay existed. And it’s so much fun! It’s just a ball, because it’s a blank canvas of incidents and characters and crazy things happening.

Which writers have most inspired your work?

Nabokov taught me how to write. I studied creative writing, but those types of classes never helped me at all. But if you read Nabokov carefully, every secret to writing is there. I love British comedians like E.F. Benson — track him down, you’ll love him. I also like Evelyn Waugh very much, that kind of British writing from the ’20s and ’30s. Comedy writing never got any better than that.

Well, while we’re on comedy writing, you improvised a monologue in Scorsese’s After Hours, right? What’s the story there?

[Laughs] You know, I was so naïve. My friend Griffin Dunne got me the part in After Hours, and I went to watch them shoot the day before my scene was scheduled. They were shooting a scene with Teri Garr, and she flubbed a line, and Scorsese says, “Don’t stop, don’t stop, say it in your own words!” And so she keeps going. And I thought, Hm, gee, he doesn’t mind if you change the lines! I went home that night and rewrote the whole thing. The next day, we get there and shoot, no rehearsal, and I start doing this nice, well-done monologue about my dead lover, and he doesn’t stop me. He’s astonished by how bizarre it is. I went on and on, and he finally did stop me. Imagine doing that. It’s both stupid and kind of brilliant to be that audacious.

How long did the monologue go on?

Minutes and minutes. I have a copy of it that I used to show at parties.

I would love to see a copy of that.

It’s coming out again [through Criterion] and I’m hoping they might include it with the extras on the DVD.

You worked as an actor for a bit, right?

After I got out of college, I worked at La MaMa — Off–Off Broadway back in the early ’70s. There were incredible people working in those days, most of whom have been forgotten, but they were brilliant actors and writers, and that shaped my artistic sensibility, working with them.

What are your memories of New York from that time?

People look back at the ’70s as the low point of New York, and it was broke and filthy and dangerous, and I loved it. I thought it was terrific, it was a wonderful place to be a young artist. You were doing things yourself. You weren’t trying to get into the business. You were putting on plays in basements downtown that you wrote yourself and 20 people would come, but it was heaven.

Are you reading anything good right now?

Yes. I’m reading a lot about the Civil War, and I’m reading a lot of Barbara Pym. The Sweet Dove Died. I consider her one of the greatest; she’s another of my teachers. In one sentence she can put what it takes other writers three paragraphs to do.

What else do you do for fun?

I like to go to Goodwill and buy things. It’s almost like therapy, it calms me down. I’m always looking for a good T-shirt [laughs] because when you live in Florida, that’s what you wear! And I love dishes from the ’50s, Syracuse China, things like that. I like handbags, so if I see a good one, I’ll buy it. The thrill is wandering around in a meditative state.

Is it true that you collect Juicy Couture?

Yes. Are you familiar with it?

Yeah, I grew up in the aughts when the celebrity “It” girls were wearing the tracksuits.

Right! It was Paris Hilton and Madonna. The handbags from the early part of the century — they don’t make that style anymore. They’re so overdesigned and overwrought, overembellished to such a degree that they fascinate me. There’s so many different styles. I must have 60 or 70 of them, all different styles. And it’s not enough. I want more.

I remember the very elaborate old-fashioned script.

Yes! Yes! Exactly. Exactly! Oddly enough, they’re not well-made. They get dirty very easily, they fall apart, the velour doesn’t wear well. If you collect Juicy Couture, you have to take very good care of it.

Something to consider. What else is new?

I’ve suddenly been rediscovered, which I wasn’t expecting. That’s turning out to be fun but a little nerve-racking. It’s out of the blue, and I’m not quite sure how to handle it. It’s more time-consuming than you would think. People you haven’t heard of in 50 years suddenly want to develop relationships with you, and people you don’t know will email and say, “You were in my student film!” And I don’t remember that. I lead a very quiet life in a trailer park, so I’m an old retired guy. I’m 78. It’s a nice, quiet, retired life. I still love writing, I still do it, and I get to go to the Goodwill every day.