Too many book critics, when writing about Tom Wolfe, attempted to echo his style. Zowie! Bam! Hrrrrmph!!!! And by failing, they all inadvertently showed why Wolfe was Wolfe. The only one who came close to matching him at the sentence-by-sentence level was Kurt Vonnegut, reviewing Wolfe’s first book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, for the Times in 1965. He himself noted that Wolfe pastiche invariably misses the mark, and he closed his (mostly warm) review with a one-sentence paragraph:

“Verdict: Excellent book by a genius who will do anything to get attention.”

That observation, blown up to a crisp 75 minutes, is at the core of Radical Wolfe, a new documentary directed by Richard Dewey, which arrives in theaters today. It’s an adaptation of a Michael Lewis profile of the Man in the White Suit himself, published in Vanity Fair about two and a half years before Wolfe’s death in 2018. It’s generally unreasonable to ask a documentary to leap off the screen as Wolfe’s words do off the page, but the film is a well-made appreciation with significant participation from his fellow New Journalists, including a couple now gone, like Gail Sheehy. Wolfe, having often been interviewed on television, is highly present as well. The documentary is sure to have the excellent effect of getting viewers to seek out Wolfe’s work or reread, revisit, reconsider.

We at New York obviously have a horse in this race. Wolfe’s best journalistic writing was done at two magazines, and although the film focuses somewhat more on his stories for Esquire, he really developed as a writer in our pages. Starting in 1963, when New York was still a supplement to the New York Herald Tribune, he wrote about teen culture, about one of the first topless dancers with silicone-enhanced breasts, about Baby Jane Holzer, about Pop Art collectors, about the embalmed self-satisfaction of The New Yorker, about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

By 1967, after that magazine closed down, he was one of the highest-profile journalists going, and his editor, Clay Felker, began bringing him—along with their friend and future colleague Gloria Steinem—to lunches with potential investors, trying to cadge some financing to take the magazine out on its own. Steinem called these sessions “tap-dancing for rich people,” and the mix of her cool glamour and Wolfe’s courtliness — not to mention that each of them had charm to spare — played well. Felker’s magazine launched on April Fool’s Day 1968, with stories by Wolfe and Steinem teased on the cover. You can read Wolfe’s feature, about the status distinctions among New York accents, here. It was long enough that Felker snapped it in half and ran it serially in the first two issues.

He wrote steadily for New York in those first couple of years, then slowed down to contribute fewer longer pieces. (Probably owing to both literary ambition and procrastination: Despite his newspaper background, Wolfe sometimes found it difficult to get a piece of writing going, and often pushed his editors’ deadlines.) In that latter run, he produced two giant works, one of which, of course, was “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s.” It’s considered one of the high-water marks of New Journalism, nearly 25,000 words about a fundraiser for the Black Panthers held at Leonard Bernstein’s apartment. The collision of high-minded leftism, Park Avenue wealth, and Black radical politics was irresistible as a subject for Wolfe to mock. He was—as the documentary notes—a man of the South, and at Yale he had been treated as a guy from the sticks, one whose doctoral thesis was rejected at first for its right-wing slant. He didn’t exactly hate Northeastern elites and their ways, but he definitely enjoyed taking a scalpel to them, and they often bled out.

“Radical Chic” is funny, and it’s mean—maybe a beat too mean. It also arguably falls on the wrong side of history. Whatever you think about the Black Panthers’ methods, they were an organization trying to break the back of white supremacy, and Wolfe was a white conservative reared in Richmond in the 1930s; their views of the civil-rights movement were probably pretty far out of alignment. The Bernstein family is still wounded by the story, and who could blame them? But it is also, inarguably, a masterpiece of observation and reporting—both at the party itself and then on the outside afterwards—and a spectacular, if perhaps overlong, piece of pure writing. Three paragraphs in, the reader is almost driven to say “who is this guy?” (A genius who will do anything to get attention, that’s who.) One can—and I do—appreciate it in a love-the-sinner-hate-the-sin way.

It’s a bit easier to enjoy “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening,” his takedown of boomer solipsism from 1976—just as sharp, but pointed toward a perhaps worthier target. I’ll let him do the work here, as he visits a let-it-all-hang-out Werner Erhard training session:

The trainer said, “Take your finger off the repress button.” Everybody was supposed to let go, let all the vile stuff come up and gush out. They even provided vomit bags, like the ones on a 747, in case you literally let it gush out! Then the trainer told everybody to think of “the one thing you would most like to eliminate from your life.” And so what does our girl blurt over the microphone?

Hemorrhoids!

From there he proceeds in a bunch of unexpected directions, connecting that moment to Louis XIV and Clairol advertising and Scientology and more. It’s surprisingly dense with research; in other writers’ hands it would likely be hard to get through. Wolfe’s language is sometimes described as pyrotechnic, but I think of it as pyrolytic: applying extreme heat and often reducing his subjects to ash.

Wolfe stayed loyal to his editors, and when Felker was deposed in a hostile takeover at the beginning of 1977, he too left New York in solidarity. The bulk of his magazine work thereafter was for Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone before he eventually shifted to writing mostly novels. But he did not entirely vanish from our orbit. In later years, he contributed a few short pieces and a couple of longer ones for us, including a majestic remembrance of Felker in 2008 and an appreciation of the photographer Marie Cosindas in 2017.

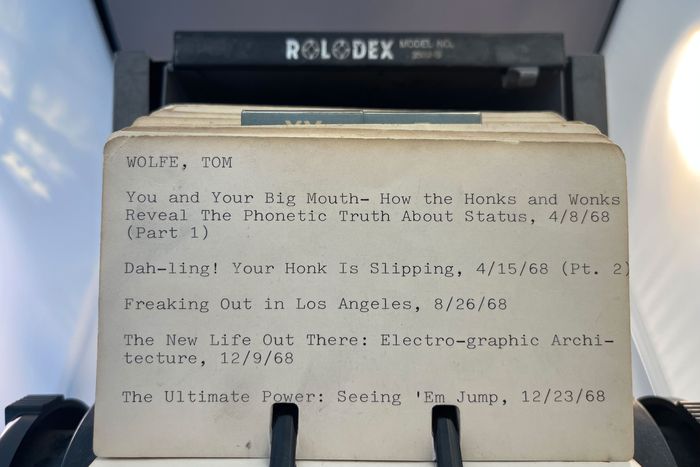

To mark the release of Radical Wolfe, we’ve dug into our first eight years of back issues—and from this page or the links below, you can read most of his work for New York, much of which has been newly digitized for the occasion.

From the Archives:

➼ “You and Your Big Mouth: How the Honks and Wonks Reveal the Phonetic Truth about Status” and “Dah-Ling! Your Honk Is Slipping!” (April 8 & 15, 1968)

➼ “Freaking Out in Los Angeles” (August 26, 1968)

➼ “The New Life Out There: Electro-graphic Architecture” (December 9, 1968)

➼ “The Ultimate Power: Seeing ’Em Jump” (December 23, 1968)

➼ “Streetfight Etiquette” (April 7, 1969)

➼ “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s” (June 8, 1970)

➼ “The Birth of ‘The New Journalism’; Eyewitness Report by Tom Wolfe” (February 14 & 21, 1972)

➼ “Advertising’s Secret Messages” (July 17, 1972)

➼ “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening” (August 23, 1976)