The Boy and the Heron opens with a sharp wail of a siren — something has gone wrong, something bad. A fire rages in Tokyo and men are pouring out into the streets to help put it out. The film’s protagonist, Mahito, rushes to get dressed and sprints into the chaos. All we hear is his breath, panting and shaking, as he arrives to see a hospital collapse into a pool of flames. Hayao Miyazaki’s film cuts abruptly to a parade of tanks rolling down the street, and the piano enters, plaintive, mournful, and almost welcoming.

On January 23, Miyazaki received his fourth nomination for the semiautobiographical The Boy and the Heron for Best Animated Feature: a category in which he previously won for 2001’s Spirited Away and was otherwise nominated for Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and The Wind Rises (2013). In all this time. Miyazaki’s longtime collaborator and composer, Joe Hisaishi, has never been recognized by the Academy, despite having written devastating scores for all the director’s films since Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Miyaszki’s second feature. Earlier this year, Hisaishi was nominated for a Golden Globe for his Boy and the Heron score, his first nomination from a major Western awards institution in his 40-year career. Yet despite being shortlisted for an Oscar nod, Hisaishi went unacknowledged by the Academy Awards again.

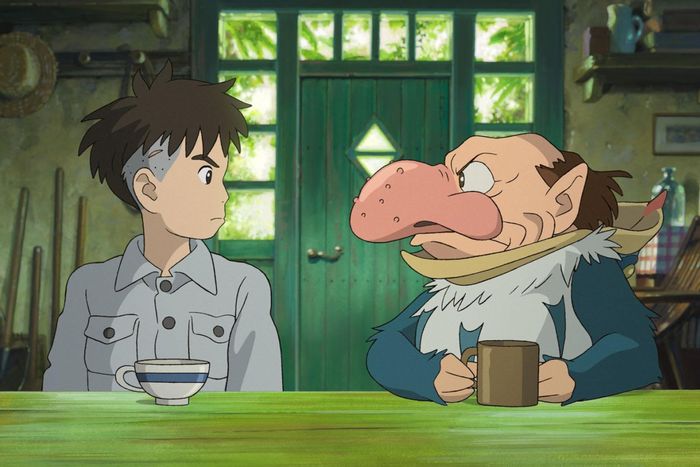

Ask any Miyazaki fan what they love about the director’s work and most of them will point out Hisaishi’s lush scores. The waltz from Howl’s Moving Castle is as distinctive as any body of cinematic music from the past 20 years, bouncing with a sense of ease and delight, breaking free from the confines of the dark, sometimes tragic film in which it’s featured. It’s more than an emotional cue for viewers or a quirky texture for a fantasy tale. Similarly, The Boy and the Heron complicates the beautiful and disturbing worlds that Miyazaki invents, putting pressure on the mythology taking shape, questioning the emotions being presented visually onscreen. Hisaishi’s music here is like a big beautiful bird puffing out its chest as much as any other character, apt for a film that must balance the usually strict rules of a Miyazaki universe with the intentionally flitting nature of a story about herons, canaries, and pelicans.

This year, new Oscars eligibility rules went into effect, mandating that a movie meet two of four criteria “designed to encourage equitable representation on- and offscreen.” In theory, this means the Academy is more open than it’s ever been to non-American filmmakers. In practice, it’s more complicated. Original Score presents a unique challenge for Academy members, who over the past few years have opted to reward predictable fare: expensive musicals (like Justin Hurwitz’s win for La La Land), Pixar movies (think Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross, and Jon Batiste’s win for Soul), and big-budget epics (Hans Zimmer for Dune or even Volker Bertelmann for last year’s All Quiet on the Western Front). The type of scores that supplement films by adding decadent strings to an already arch period piece or twangy guitars to a western.

The most recent and welcome upset in recent years was Hildur Guðnadóttir’s eerie, displaced score for Joker, a movie that could have felt far cheaper and less interesting without atonal, Icelandic music to accompany it. The original music upended viewer expectations in ways even the script itself couldn’t, leaving the audience jilted and intrigued. But it’s been difficult for East Asian composers to break through, even when their films are nominated in other categories: Jung Jae-il’s delightfully twisted Parasite score gave it the sound of an 18th-century period piece. Eiko Ishibashi’s jazzy, cool music for Drive My Car felt as fittingly retro as the film’s titular 1990 Saab. Neither was recognized by the Academy.

Hisaishi doesn’t need the nomination more than anyone else needs the nomination — he’s been decorated by other awards bodies, including the Japanese Academy Awards. His fans love his work, and Miyazaki clearly knows how valuable he is. But in a year when his musical jumps and dazzles make it as beguiling as ever to see a cartoon child splattered in the face with fish blood, it would have been nice to see the Oscars make a bigger moment of what is likely Miyazaki and Hisaishi’s last project together (if The Boy and the Heron is indeed the director’s last movie). Alas, Hisaishi will return to New York this summer to play Madison Square Garden, and that’ll be way more fun than going to the Oscars anyway.