Playwright and screenwriter John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: A Parable made its debut Off Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club in 2004, the same year the Catholic Church released a report saying that more than 4,000 priests in the United States had molested more than 10,000 children in the prior 50 years. Shanley’s play focuses on two nuns, Sister Aloysius Beauvier and Sister James, working at a K-8 school in the Bronx in 1964 who fear that a charismatic young priest, Father Flynn, is sexually assaulting a Black student who has just transferred in. The show riveted audiences both for its performances by Cherry Jones, Brían F. O’Byrne, Heather Goldenhersh, and Adriane Lenox and for Shanley’s refusal to definitively answer the question of whether Father Flynn had abused that child. The play ends instead on the starkest of notes: Having gotten Flynn thrown out of her parish through an act of deception, Sister Aloysius — the show’s unflinching icon of justice and truth — breaks down with emotion as she admits to Sister James, “I have doubts! I have such doubts!”

The play would move to Broadway, where it won four Tonys, including Best Play and Leading Actress for Jones as Sister Aloysius, and then to Hollywood, where Shanley and the film’s entire cast, which included Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Viola Davis, and Amy Adams, would be nominated for Academy Awards. The play also won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Twenty years later, the revelations of historical abuse of children and vulnerable adults in the Catholic Church have only grown exponentially. A revival of Doubt begins previews February 2 at the American Airlines Theatre, with Tyne Daly as Sister Aloysius and Liev Schreiber as Father Flynn.

In a gorgeous preface to the script, Shanley reflects on the era in which the play takes place. “Looking back, it seems to me in those schools at that time, we were an ageless unity,” he writes. “We were all adults, and we were all children. We had, like many animals, flocked together for warmth and safety. As a result, we were terribly vulnerable to anyone who chose to hunt us. When trust is the order of the day, predators are free to plunder. And plunder they did.”

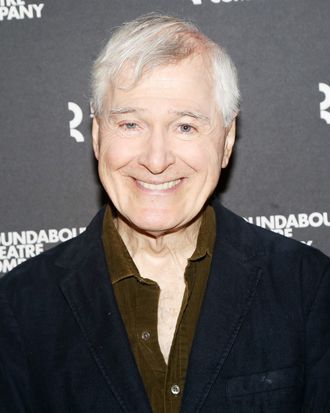

Shanley spoke about his thoughts on the play today and shared for the first time his own childhood experience with an alleged serial pedophile, which inspired the story.

I know you grew up Catholic in the Bronx. How would you describe the Catholicism of your upbringing?

It was certainly more understandable, because it didn’t feel like it was constantly shifting, and it didn’t have scandal in the foreground. As kids we were all quite aware that the clergy we were dealing with were fallible, and more than that. There was a lot of sexual repression and weird sexual behavior, but kids understand that, at least in the city. Parents, maybe, with a level of belief in the spotlessness of the clergy, were blind to things. But the kids saw it. We all knew.

Really? The reality of priests abusing kids was no surprise to you?Absolutely not. I’ll just speak for myself and the people that I saw around me. I have two sons. I remember one of them saying he was almost mugged on the way home, and not for the first time. I said, “You know, no one has ever tried to mug me. What are you doing?” And he said, “Dad, I’m a teenager. That’s who it happens to.”

When I was a teenager, I got mugged; I dealt with all sorts of people after me for money, people after me for sex, people after me for what they didn’t even understand or I didn’t understand. That age range, it brings out everything in everybody. Because they’re going through the transition right then, all of their issues are visible. Their sexual ambiguities, their vulnerability, their credulousness — it’s just right there.

You’ve said that you had long wanted to write about the nuns who had taught you in grade school. And you dedicate the play to them. But what inspired the specific idea of a story about a potential abuse situation?

It started with the title. On a break at a rehearsal, I said to a friend of mine, “I’m going to write a play called Doubt.” He said, “What’s it about?” I said, “That’s all I got.” But I knew it was a good … what Jung would call “attractor,” that if you put that down into your unconscious it would pull things to it.

I went to a private school in New Hampshire for two years. I’d been thrown out of all these schools in New York, and this right-wing Catholic lay organization Opus Dei adopted me. A priest in that organization said he had connections with this private school, and he was going to see about getting me in there.

He came back and said that they were willing to give me a two-year scholarship, that my parents would just have to pay for my food. Then in August my mother, who was a long-distance telephone operator, had not heard from the school, so she called the headmaster and said, “I just wanted to know when you want my son John to arrive.” And the headmaster said, “I’ve never heard of your son; I don’t know what you’re talking about.” The priest was crazy.

My mother burst into tears, and the headmaster said, “Look, put him on the plane. I’ll talk to him.” So I went up to New Hampshire, sat down with this guy at a diner. He figured out my credits on a napkin. I went to that school with the deal that the crazy priest had presented through the generosity of this headmaster.

While I was there, I was taken under the wing of the head of the English department. And that guy was a predator. Which I did not know. We found this out much later. All around me he was abusing students, but not me. A couple of times it got broached, and I was immediately fiercely protective of this guy, because he had been my champion.

I was there for two years, I left, and sometime afterward I got an inkling because I stayed in touch with him, continued to see him, and he kept getting thrown out of schools, though he didn’t put it that way. But he’d end up on his feet in another school.

One time I saw him with this young guy about my age, and he introduced him as his son. And I was like, That’s weird. And the young man looked really sad. That was the beginning of my understanding that this guy had been a predator.

Many, many years later, I got a letter from him. As I suspected, the letter said he was going to die of cancer.

I decided, I am not going to answer this letter, and I’m not going to visit him because of what he has done. When he died, I read in his obituary that attending his funeral were his four adopted sons. Four.

I’ve never told anybody that story. Back at the time of writing Doubt, I kind of buried it for myself. I wanted to write about the time in my life before I’d ever met that guy. But that is definitely part of the deep background of the play.

I’m sorry that happened.

I’m sorry for all of the ones that he picked. I’ve thought since that maybe I was his justification, that he’d done something right, you know, that he spared this one boy.

Given how he’d helped you, was it a shattering experience to learn what he’d done?

No, it just added a slight level of nausea. Life is complicated. People are complicated. Whenever you think someone else is the bad guy, look in the mirror. We’re all wild creatures trying to make believe we’re civilized.

It can be very difficult to face yourself. I went through a period, which at the moment seems to be quiescent, where every morning in the shower I remembered another ten terrible things I had done. That went on for like a decade. I was like, How many things did I do? Haven’t I gotten to the end? It was like, No.

It’s interesting — I find a similar dynamic in your plays. Terms like villain and hero don’t really seem to fit your characters; it’s always a both/and. Even in Doubt, we’re clearly rooting for Sister Aloysius, and yet she can be incredibly cold.

Yeah, and maybe she’s done something very, very wrong.

That ending … It’s so unexpected to discover that she, too, is riddled with uncertainty. Was that always where you saw the play headed?

I didn’t know it until I wrote it. The reason that it’s powerful is I came to it like the audience comes to it, at the moment and not before.

Would you say you see yourself in Sister Aloysius, Sister James, or any of the other characters?

You know, of all of my plays I’m probably the least in Doubt. I’m a silhouette described by the presence of them and the absence of me.

Sister James is a real person. She’s still alive. I didn’t change her name, and when I first did the play, in early previews, a person who knew me from the Bronx said, “I told Sister James that you’re doing a play and she’s in it. She’s very excited, and she’s coming to see it.” I was so alarmed. I thought she was dead. It was suddenly like, I’m going to be sued!

She came with another nun. We sat together, and the lights went down and then came up on the set, which I think was an exact replica of the garden that was outside of their convent. And I’m looking through this magic window right into the past. It was one of the strangest experiences of my life. Very moving.

It’s been 20 years since the show first premiered. How do you think it will resonate today?

When I did the play originally, I think the audience as a society was much more complacent than it is now. I think a lot more people will be walking into the theater this time already in a state of conscious doubt than when we did it the first time. And that will make it a different experience. I’m interested to see what that experience is.

In the preface to the play, you talk about the experience of doubt as a profound moment of crisis, but also a gift, a chance at liberation from old and inadequate ways of thinking or acting. I find that such a hopeful idea. But then in your plays, that gift often comes at such a terrible cost.

I don’t mind that it’s that way. I think it’s much more interesting, more important, more valuable to notice the way things are than to have even a single moment of thinking you know the way things should be. Because the second thing is just egomaniacal. You think you know how things should be? You think you know what justice is? Justice is the most frightening word there is as far as I’m concerned. Anything but justice.

Why do you say that?

Look around at what we’ve done. Let’s hope to God there’s not justice.

I’m really struck by how you refuse to allow us to rest when it comes to good and evil.

I just don’t want to be alone. I want other people to share my point of view with me. And my point of view is that we’ve all done stuff and carry that around.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.