Yvonne Wells began quilting in 1979, nearly at the age of 40, for the reason most people begin quilting: to keep herself and her family warm. Born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Wells was a schoolteacher at the time and entirely self-taught in her art. Her husband one day handed her a picture of a quilt clipped from the local Tuscaloosa newspaper and challenged her to re-create it. She did so perfectly, igniting a deep spiritual calling that found her abandoning the conventions of the craft. Wells pieced unusual shapes and fabrics together. She attached buttons, yarn, zippers, snippets of text, and even police tape. “My work is not traditional,” she has said. “If they tell me to make my stitches small and tight, I’ll leave them loose.” She added, “This is truly me: the unfinished, the unpolished.”

Now 84, Wells is considered a visionary on par with historical figures like the “Mad Potter” George Ohr and the quilt-maker Rosie Lee Tompkins. Her large-format quilts contain both the epic detail of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings and the crude charm of all good outsider art. She has made pieces based on Proverbs and the Seven Deadly Sins, for the White House Christmas tree and the aids Memorial Quilt, and as backdrops for the concerts of Cicely Tyson, Harry Belafonte, James Earl Jones, and Sidney Poitier. But she is best known for her narrative compositions depicting formative moments in Black history: the Middle Passage, the Great Migration, the civil-rights movement. Her work is rich with American flags and Statues of Liberty and crosses, reimagining and remaking the familiar iconography of this country into a deeply spiritual, almost joyous celebration of Black struggle. “Every time I would make a civil-rights quilt, it was not ever made out of anger,” she once said. “I couldn’t do it.”

Her show at Fort Gansevoort, “Beyond Patchwork: The Abstractions of Yvonne Wells,” at first glance seems to mark a departure. Gone is the great narrative sweep; instead, we have bold shapes, kaleidoscopic arrangements of fabric, geometric symmetries. To find the themes of her more famous work, one must look closer — and there, in the very materials used, in the warp and weft of the design, we will encounter the unfinished, unpolished evidence of both Wells’s life and many others’.

Unwind (2010) is mainly black and white, its curving lines, tails of shooting stars, stripes, and polka dots evoking a scene from outer space or perhaps a holy garden. The title may refer to the unraveling of a ball of heavy yarn and the shape that unraveling might take. African–American Squares (1994) gives us horizontal bands of red squares set like stones upon patterned blocks, a flag made of the African prints she received as a gift. This quilt was used regularly as a tablecloth during Thanksgiving celebrations at her Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church in Tuscaloosa. This is an art with utility — you can gaze at it, eat from it, and incorporate it into ritualistic communion.

Even among all this abstraction, though, symbolism makes an appearance. Crazy Quilt (2017) is an uneven grid of panels featuring different objects: a dismembered white hand, a cross, a sun. There are musical notes, upside-down newspaper headlines about the end of the Vietnam War, men walking on the moon, Amelia Earhart. There is a strip of a Confederate battle flag, a menacing motif in a body of work that is otherwise so colorful and lively.

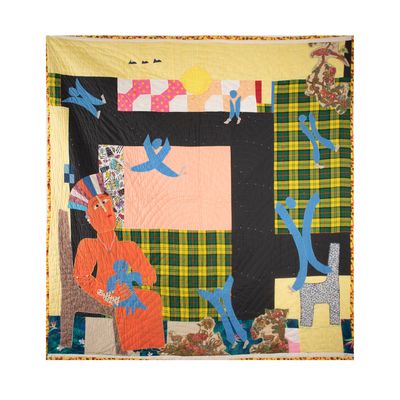

I understand the gallery’s temptation to focus on abstraction. First, exercising different conceptual muscles is essential to Wells’s wide-ranging practice. Second, we are miserably awash in wave after wave of figurative painting, and while Wells’s figures are blocky, I am always grateful for a break. Still, I wish more of her larger narrative works were present, such as my favorite piece on view here, Sit Down (2003), which features a seated woman with color blocks representing her hairstyle. She holds a baby in her lap and looks up at what could be bluebirds or angels but Wells says are children. The woman is situated among flowers, and a red parrot is looking down from a branch. This is a beautiful, sacred space.

That is not to say that her abstract quilts don’t tell a story. Wells works with ephemeral, disposable, and found materials, often assembling scraps of cloth in eccentric ways. “Gathering ‘stuff’ to make a quilt is very rewarding because there’s no telling what I may find,” she once said. “If I saw something out there in the street that I could use, I would jump out of the car and go get it. Or if something is lying around the house — my husband’s clothes or children’s clothes — I would use it.” Like a traditional African American quilt, her pieces appear made with a sort of consummate haphazardness, packed with meaning. Parts don’t quite fit, then — boom — click into place.

The materials include the kente cloth, which was originally used by African royalty, and the Dutch wax print, named after the traders who brought fabrics inspired by Indonesian designs to West and Central Africa. These are quilts, in other words, that contain the great movements of the African diaspora instigated by colonialism and enslavement. Wells is attempting to capture the vertiginous pull of history, perhaps best expressed in Round Quilt (1987), in which a circular pool of various fabrics seems to be swirling down a drain. This is work that feels both simple and complicated, alive with contradiction, and bursting with a humanity whose story is still

being written.