Warning: Numerous spoilers for the Batman story “Hush” follow.

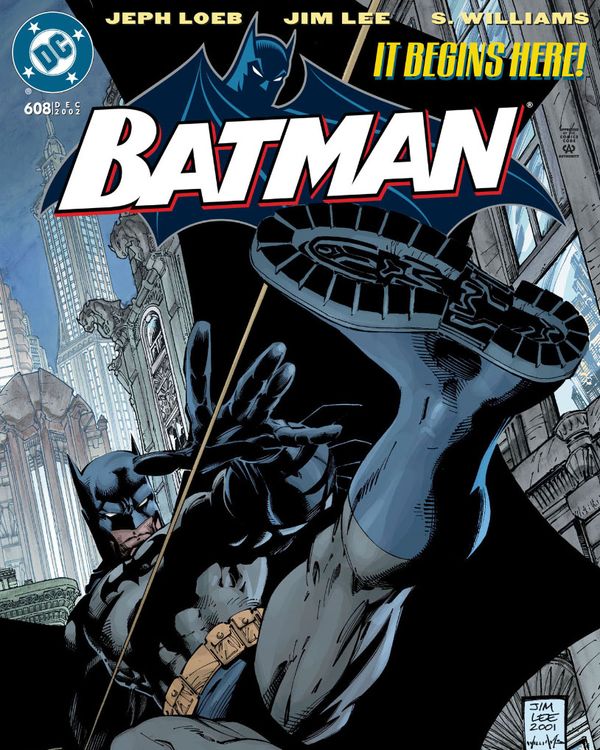

The new millennium did not start well for DC Comics’ Batman: In both 2000 and 2001, the monthly title failed to crack the top 100 of issues shipped to comic stores — and the first nine months of 2002 looked equally grim. That October, DC signaled a course correction, shipping Batman #608 with a new cover logo and a three-word all-caps cover line that made clear changes were afoot: “IT BEGINS HERE!”

What that proclamation referred to was “Hush,” a 12-issue narrative written by Jeph Loeb and penciled by Jim Lee, and it provided a massive boost to the series’ popularity. In a recent interview, Lee, who is now publisher and chief creative officer of DC Entertainment, said single-issue sales of Batman jumped from around 66,000 to more than 330,000 during the story’s run. The final issue in the arc, Batman #619, was the most-shipped issue to comic book shops for all of 2003. Four of the nine other Batman “Hush” issues shipped that year were also in the top ten.

Two decades and two imprint-wide reboots later, “Hush” is as popular as ever. It is frequently cited as one of the all-time best Batman stories, it was adapted into a well-regarded 2019 animated movie, and director Matt Reeves included several references to it in this year’s The Batman. Earlier this week, DC released Batman Hush: 20th Anniversary Edition, a $49.99 hardcover that is at least the 13th (!) different book-length edition of the story to be published since 2004. According to Lee, “Hush” brought significant numbers of both new readers and “relapsed fans” into comics. It’s not hard to see why: Loeb’s rapid-fire pacing and the fluidity of Lee’s intricately detailed artwork make this the graphic novel equivalent of a Michael Bay movie.

It is most definitely not, however, a story that benefits from repeat readings: Underneath all the flash-bang action, it’s a clumsily written, convoluted tale that’s full of gratuitous characters, narrative inconsistencies, and a wholly unsatisfying conclusion. For all of those reasons, I’m here to argue that this latest deluxe edition of “Hush” should also be the last.

Loeb’s initial pitch to Lee was a team-up on a “great murder mystery” with “all the greatest Batman villains” that would “lean into the fact that Batman’s not just a great crime fighter, he’s also an amazing detective.” It was a smart move on paper. One of the joys of reading Batman stories is marveling at the hero’s preternatural ability to follow a trail of carefully placed breadcrumbs. The first issue of “Hush” features not one, but three of Batman’s longstanding adversaries — Killer Croc, Catwoman, and Poison Ivy — along with plenty of action. After Batman rescues an heir to a chemical-company fortune, his attempt at recovering a $10 million ransom is foiled when an unseen fourth antagonist cuts his rope line, causing him to fall to his near death in the very spot where his parents were murdered. This setup provides any number of potential clues for where the story is headed: Did eco-warrior-cum-terrorist Poison Ivy target the heir because his family’s company created a defoliate that “makes napalm look like lipstick”? Was Croc, described as having recently changed into something “more savage than human,” affected by some sort of chemical spill? Was the famously wealthy Wayne family somehow involved with making chemical weapons?

The answer to all of these questions, as well as virtually every other question raised by the red herrings and misdirects in “Hush,” is no. Characters ranging from Lady Shiva to Lex Luthor and Leslie Thompkins to Lois Lane are introduced for no apparent reason other than checking a box on Loeb’s extended-Bat-universe bingo card, story logic be damned.

It’s tempting to view Loeb’s padding of “Hush” with a grab-bag of dead-end cameos as a feature and not a bug, a tactic for keeping readers sufficiently off balance so that they ignore the fact the “great murder mystery” makes no sense. The plot tracks the sudden reappearance and subsequent murder of Bruce Wayne’s hitherto never-mentioned childhood chum Thomas Elliot. Except, it turns out, Elliot isn’t really dead; he is, however, a psychotic sociopath who tried to murder his parents by severing the brake line on their car. After the crash, Bruce’s physician father saved Elliot’s mother’s life … and apparently, Elliot has had a “mad on” for Wayne ever since.

In our world, deducing that Elliot is the eponymous madman of “Hush” is painfully easy. It’s a safe bet that the new villain will be the one character nobody has ever heard of before. In the world of the story, however, it’s all but impossible to figure out. Despite Batman repeatedly reminding readers that “the answer lies somewhere in the details,” the details that are included generally show the opposite to be true. To take one example, Loeb’s explanation for the fact that multiple people witnessed Elliot’s apparent death is that they actually saw Clayface, a villain who can famously transform his outward appearance, posing as Elliot. That’s a plot twist that might have been possible to guess — except for the fact that Elliot’s body was subjected to an extensive (and extensively detailed) police autopsy, which Clayface shouldn’t be able to fake. It’s tough to find the answer in the details if the details undermine the actual story.

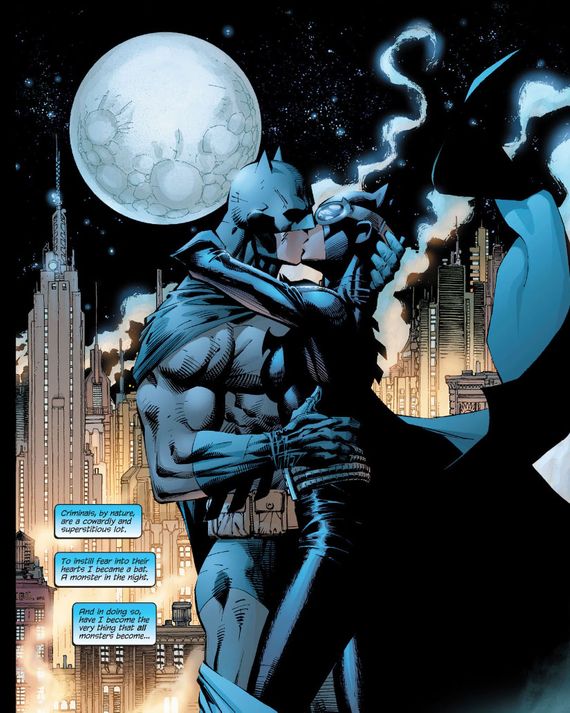

That type of blithe disregard for consistency extends to characters’ well-established backstories, which Loeb leans on to make the emotional arcs in “Hush” resonate. The hastily assembled scenarios he uses to get to those payoffs, however, require characters to act in ways that contradict what we already know about them. Bruce Wayne had spent his entire adult life sublimating his desires, adhering to a strict moral code, and keeping his vigilante identity a secret. In the B-story of “Hush,” a pair of sweaty, stolen kisses between Batman and Catwoman leads to his revealing his secret identity and nearly abandoning a “no-killing” creed that is as much a trademark of his character as pointy ears and a cape. The Joker is famous for acting irrationally and always insisting on being center stage; in “Hush,” he agrees to serve as a patsy in someone else’s grand conspiracy. Even minor characters aren’t spared: Leslie Thompkins is a committed pacifist who disapproves of Batman’s vigilante tactics; in “Hush,” she tells Catwoman to join a gun battle in the middle of an opera house lest the men “have all the fun.”

It’s possible some of these problems could have been glossed over with better writing. In his earlier, more satisfying Batman stories like “The Long Halloween” and “Dark Victory,” Loeb showed admirable narrative restraint. “Hush,” by contrast, is filled with a mishmash of Yogi Berra-isms (“I seem to have more family than I seem to have”), clumsy constructions (“You and he are working together now?”), nonsensical similes (how exactly would a defoliate ”look like lipstick”?), and reversed idioms (“people in ice water want Hell”). Bruce Wayne’s internal monologues are especially painful: Lines like “Have I become the thing that all monsters become — alone?” make a famously brilliant tactician sound like he’s auditing an Intro to Psych course at Gotham High.

But the worst sin of all might be that Hush is a lame, unoriginal villain. Batman has the most recognizable rogues’ gallery in comics because its members represent archetypal anxieties and primal emotions. Poison Ivy was once a shy genius who was taken advantage of; as a supervillain, she personifies the fear of being overpowered by seduction and the danger of sexual obsession. As children, Killer Croc and Two-Face suffered abuse at the hands of alcoholic caregivers; as adults, they epitomize the unforgiving ferocity of the natural world and the cruel randomness of fate. Hush, on the other hand, was a brilliant kid with wealthy parents who grew up to be a handsome, world-class surgeon — full stop. (It wasn’t until other DC writers took a crack at the character that any attempt was made to account for his behavior.) The explanations for his patricidal rage and his all-consuming hatred of Bruce Wayne are so flimsy as to be nonsensical — and his identity as a villain is essentially just a pastiche of other, more interesting characters, from Bane to Black Mask. The reveal in the story’s final pages that Elliot was working with a resentful Riddler — “I used to be a somebody in this town. Now, everybody has a gimmick” — is a fitting coup de grâce. It’s never entirely clear what either character’s ultimate motivations are, or why they needed to work together at all.

For the legions of diehard “Hush” fans, these gripes are akin to criticizing a roller-coaster for being incoherent — and if you’re just interested in the thrilling, breakneck ride, there’s lots of great scenery: “Hush” is among the best works of Lee’s long and storied career. His artistic and narrative sophistication is perhaps best illustrated in “Hush”’s lush, frame-worthy full- and multi-page spreads. Take, for example, a single moonlit image that occupies two full pages in the first issue:

Batman has flung himself almost horizontal to the ground as he tries to shield a young boy from a feral Killer Croc, who here resembles a xenomorph from Alien more than a human with an atavistic condition. This is the story’s first real fight, but if you rush past it, you’ll likely miss a tiny image of Catwoman, completely in shadow, skulking in the background of the right-hand page. She’s framed by the crook of Croc’s left arm, which happens to be holding a briefcase full of cash. It’ll take another six pages before Batman realizes that she absconded with the money. The fact that this isn’t even among the top dozen of “Hush”’s best-known drawings only highlights the impressiveness of Lee’s work.

And in the end, it’s the art and not the story it supports that is “Hush”’s true legacy. The hyper-stylized Tim Burton and Joel Schumacher Batman films of the late 1980s and 1990s featured exaggerated characters and sets that were easily identifiable as coming from the comics. In the years immediately preceding “Hush,” Batman was drawn, mostly by Scott McDaniel, in a style more evocative of animation than real life. But ever since then, Lee’s brooding, noir take on both Batman and Gotham City has been the lens through which every other portrayal of the Caped Crusader and his environs has been filtered, including, perhaps most notably, Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy and The Batman.

Like previous graphic novel versions of Hush, the 20th-anniversary edition features a handful of extras, including a “20 Questions With Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee” feature, reprints of some covers, and annotations Lee did back in 2005. The most hyped add-on, which was presumably included to entice people who already own an earlier edition, is a new, five-page story by Loeb, Lee, original inker Scott Williams, and original colorist Alex Sinclair. Titled “Prologue: The Aftermath,” it shows how Elliot survived being shot and falling into Gotham River in the climax to Batman #619 and concludes with an all-caps “TO BE CONTINUED …!” Unlike the original cover line on Batman #608, however, this reads more like a threat than a promise. It’s also completely unnecessary. Over the past two decades, both Thomas Elliot’s background and his post-“Hush” activity have been extensively explored by other writers. The original Loeb-Lee story has had a good run. Unlike its infamous supposedly dead characters, it’s time for DC to let it rest in peace.