I don’t care about any new animated show this year more than I do the reissue of a 24-year-old one with dated animation and a frustratingly incomplete story. This week, the original 1997 anime adaptation of the late Kentaro Miura’s manga Berserk, only ever released on home video domestically, came back in print in the United States and sold out within a day of its debut this Tuesday. Luckily, knowing the show had been unavailable to buy or legally stream for about a decade, I had planned ahead. As its distributor Discotek raced to get new copies out to stores like Crunchyroll and Amazon this week, I poured some bourbon, hit play on my preordered Blu-rays, and dove back into the beauty and brutality of Berserk.

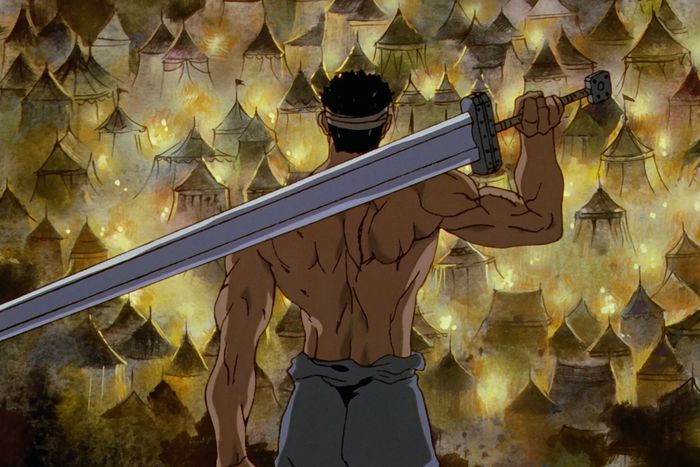

Set in a dark fantasy world dominated by feudal empires and similar to medieval Europe, the show follows Guts, a burly wall of an anti-hero racked with guilt and trauma. We meet him in the first episode as “The Black Swordsman,” a cruel and committed slayer of the demons that prey upon the countryside. An abused child who grew into a violent and cursed man, Guts wields a colossal sword — a heavy slab of metal seven feet long and perpetually soaked in blood — and a gruff, merciless attitude. He also has only one eye and one arm. At the end of the first episode, after Guts destroys a demon who reminds him of his past, the show immediately flashes back to his teenage years as a young warrior, before he lost his eye, his arm, and his humanity. This Berserk anime, which preceded a workaday 2012 film series adapting the same arc and a reviled 2016 adaptation, is largely a prelude to Guts’s story in the ongoing manga: Over the course of 25 episodes, we watch his power grow and his shell soften as he finds allies in the warriors Griffith and Casca and overcomes the traumas of his childhood, even as he improves his skills as a mercenary. As the young Guts begins to find meaning in those friendships and relationships, though, tragedy rips them away.

We won’t spoil more than that, except to note that the specific horrors of the series include grotesquely graphic cruelties and shocking sexual violence. Like other epic series such as Game of Thrones or Vikings, Berserk is known for not pulling punches, and not only are the show’s demons literal agents of hell, they also prey upon the psychological and societal ills of the medieval world Miura created. In the story, torture, rape, and genocide are all wielded to break individuals and kingdoms, as they are in real life. Nonetheless, we empathize more and more deeply with Guts as the show progresses; he is introduced to us as a vicious monster, but we come to understand the experiences that shaped him, and how he keeps struggling through them, despite the pain they caused him.

Every episode begins with a narrator’s epigraph on causality and free will — “Man has no control, even over his own will” — but Guts’s actions prove we’re not meant to believe that: The point is that no matter what he faces, Guts continues to strive. In Miura’s manga, the same quote appears, but it goes on, hammering that point home, “Man takes up the sword to shield the small wound in his heart sustained in a far-off time beyond remembrance.” Berserk may be a hyperviolent story, but it’s not an edgelord’s power fantasy: It’s a dark tragedy about how difficult waking up to a ruthless world every day can be, especially if you have dreams beyond fighting.

The animation in the 1997 adaptation underscores the point. Think of the most impressive, immersive action animation you’ve seen, old or new, and you’ll likely think of characters in motion. The fluidity of the bike races of Akira and staccato styling of Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse often feel like the most important elements of those films’ success. But they’re not. What’s most important is tempo and pacing — balancing the fluid, high-budget action with deliberate, evocative character building. Berserk has that in spades — in part because director Naohito Takahashi and studio Oriental Light and Magic (which also released Pokémon the same year) had to allocate animation budgets carefully. As a result, it’s full of conversations where the only visible movements are lip-flapping, slow pans over painted backgrounds, and the occasional still spliced right into an action scene, but they all still punch hard.

The show’s most poignant episode, “Bonfire of Dreams,” is built largely around a conversation Guts has with Casca, standing alone and overlooking his comrades’ camp at night. The scene’s emotional power comes from its stillness, its music, and an artistry that amounts largely to simple, slow animation framed in front of gorgeously painted backgrounds. The scene doesn’t need much else, because Miura’s source material, the direction by Takahashi, and the art direction overseen by Shichirō Kobayashi do all the work that flashy animation cannot. Neither anime adaptation of Berserk released since could touch this show’s sense of style.

But that limited, controlled cartooning also feels like the most undersung aspect of anime series. The manga produced by Miura is legendary and has inspired fellow artists, metal bands, and video-game series like Castlevania, Dark Souls, and Elden Ring for decades. The manga is also intricately detailed, a work that relishes in double-page spreads of supernatural landscapes and the details of every segment of Guts’s black armor — to say nothing of the hundreds of pages in which he swings his sword. Miura, who died in 2021, created a masterwork, and though this translation doesn’t capture the full richness of his pencils or the entirety of his story, it remains the best adaptation we have of Berserk. Like Guts, it will never be whole, but in a way, that’s fitting.