As the coronavirus pandemic raged on last year, animation proved to be as close to the ideal medium for remote production as the moving-pictures industry is likely to get. So it’s no surprise that 2021 was a year as rich in remarkable animation as any in recent memory, even if most of the year’s animated output began production long before lockdowns commenced. This year’s best animated films and television series were astoundingly diverse, from a form-busting documentary about the immigrant and queer experience centered on real-world tragedies, to an experimental limited-series anime preoccupied with remarkably abstract and dense existential musings.

The ten best animated titles of 2021 were almost entirely creator driven and — perhaps unsurprisingly, considering that our country’s film and television industries’ most hallowed taste-making bodies still tend to see the medium as an afterthought — almost entirely foreign made. (Five of our favorites are from Japan and three others from Europe.) Our hope for 2022 is that major American entertainment companies come to appreciate animation as an art form of astonishing breadth and depth and not simply a cash cow for lazy sitcoms and the milking of preexisting IPs. In the meantime, we have these astounding works, as good an argument for the power of animation as any other.

.

Belle

Belle is already anime superstar Mamoru Hosoda’s highest-grossing film, and that’s before it even hits theaters in the U.S. This is no surprise. A visually stunning retelling of Beauty and the Beast for a digital age, Belle is gorgeous to look at and packed with things to say about our increasingly digital lives and how we socialize within social media. It manages this through both the artistry of its virtual world — known in the film as U, a shimmering, hypersaturated, brand-sponsored infinite reality where identities are created, consumed, and closely guarded — and its characters. Heroine Suzu (the Japanese word for “bell”) is a shy and deeply scarred young girl who finds fame and acceptance within U until her path to stardom collides with the antisocial and (virtually) violent Beast, with whom she forges a strong bond. Despite the homages to the Disney film (the camera movements in the dancing scene!), you’d be wrong to call it a remake. Instead, Hosoda and Studio Chizu, with the help of Cartoon Saloon and Disney veterans Jin Kim and Michael Camacho, made a film more about one young girl’s journey back to life after enduring tragedy, rather than a fairy-tale version of true love. And it hits all the harder for it.

.

City of Ghosts

Elizabeth Ito, the creator of City of Ghosts, seems hyperaware of the power art can hold in a society divided by hate. “Even as we were making it, there was this sense of, We really need this show. Whatever we can make to help us recover,” she told Vulture in an interview about the Netflix series, which feels like a succession of confident skips through L.A.’s diverse and historic neighborhoods and communities. The ghosts in the show represent the living memories and oral histories locked inside decades of urban change, and its protagonist, Zelda (August Nuñez), acts as a kind of documentarian, cataloguing and explaining that change to viewers. City of Ghosts is an all-ages show, one that at times feels like it’s halfway between Dora the Explorer and Planet Earth. At every turn, though, it’s more charming than both of those. The animation and characters may seem simple, but the stories and background art are strikingly complex; both reflect the realities and fantasies of one of America’s richest cultural melting pots.

.

Encanto

Sixty movies in and 84 years since the debut of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney Animation’s newest film feels as sharply made and warmhearted as its classics. Appropriately, Encanto, co-directed by Jared Bush, Byron Howard, and Charise Castro Smith, is obsessed with the idea of legacy and how families carry their name and extraordinary secrets forward — a relatable idea, even if not everyone can relate to controlling the weather or changing shape as Encanto’s Madrigal family can. Heroine Mirabel (Stephanie Beatriz) has no special powers, and she feels trapped and unworthy in a movie that has no single villain aside from the extreme pressure her family puts on her. Both the movie’s fun and its emotional heft shine through in the many one-on-one scenes with her family members, from her sisters, Luisa and Isabela, to her estranged uncle, Bruno. Encanto’s core argument is that the roots that anchor us to family sometimes go even deeper than blood reveals, but that makes them all the more crucial to nurture.

.

Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time

The final installment of director Hideaki Anno’s Rebuild tetralogy of films revisiting his iconic series Neon Genesis Evangelion is a masterpiece, full stop. It may have taken years to get it finished, but you could argue this wound up being to the film’s benefit on a cosmically meta level. Every minute of Thrice Upon a Time refers backward, by design, to what came before but never feels beholden or shackled to that past. Over and over, especially in the film’s last act, the director literally and metaphorically closes the door on his long-suffering family of psychologically damaged pilots of giant humanoid robots — breaking the fourth wall as he goes on to express what we can only interpret as being his own sense of closure for the series. As the end of a nearly three-decade maxi-series, Thrice Upon a Time all but demands that viewers have at least seen the first three Rebuild films (streaming on Prime Video), if not also the TV series and theatrical films, End of Evangelion and Death (True)² (on Netflix). We also recommend the documentary Hideaki Anno: The Final Challenge of Evangelion to get a fuller sense of the director’s work ethic. The payoff is worth it.

.

Flee

How does one come to terms with a childhood filled with unspeakable suffering and tragedy? For Amin, the protagonist of the moving visual marvel that is Danish French director Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee, the answer is to run from it — or, at the very least, hide it, even from those he loves most. The story’s entwined dual narratives follow Amin’s family’s desperate attempts to flee a war-torn Afghanistan over the course of more than a decade and his own experience coming out as a gay man, harrowing twinned journeys of self-knowing and survival. The film masterfully juggles two visual styles — one more realistic and rich with color, the other awash in dark grays and beiges and sketchy as only our most difficult and distant memories are — interspersed with real-life footage of refugees and cable-news stories from the time of the Soviet-Afghan War. Its storytelling style, which centers its own director’s halting and painful conversations with his friend and main character, makes Amin’s process of reckoning with his past as much the focus as the stories themselves. It’s as masterful a documentary as it is an animated film, and it’s one of the year’s best movies.

.

Mad God

For three decades, legendary visual-effects supervisor and director Phil Tippett (Star Wars, Jurassic Park, RoboCop) was hard at work on a pet project titled Mad God, and for three decades, no one was sure it would ever be completed. The final product is about as different from any of the animations on this list as you can get: a “fully practical stop-motion film” that happens to be violent, bloody, and redolent of a descent into hell, complete with demonic monsters, gnashing teeth, sadistic doctors, and screaming children. It’s biblical to the extreme — even kicking off its proceedings with a quote from Leviticus about razed cities — but it’s a vision realized in the form of a Gumby episode. This is something Tippett worked on in bursts of productivity on evenings, weekends, and days off; on his off time, he chose to make an elaborate, somewhat cryptic infernal fable that raises more questions than it answers. Mad God is a lot, but it was worth the wait.

.

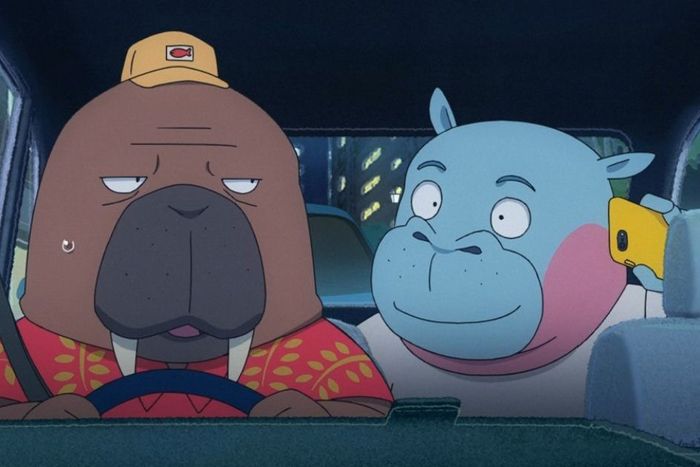

Odd Taxi

A pitch-perfect noir filled with mystery and intrigue. A sublime skewering of contemporary society in Japan and beyond. A laugh-out-loud drama and a dread-filled comedy. Odd Taxi is all of these things. It is also an anthropomorphic romp starring a charmingly misanthropic taxi driver who believes he’s a walrus; an alpaca nurse in over her head and the gorilla doctor she works for; an almost too smart baboon yakuza and his rival, a rapping porcupine; a megalomaniacal hippopotamus internet personality; and more. Director Baku Kinoshita’s first anime — with a script by another anime newcomer, Kazuya Konomoto, that’s so sharp you could slit a throat with it — is a marvel. Its visual style, arguably more at home on Nickelodeon than on Crunchyroll, is an instant standout (all the more impressive considering that, unlike most anime, much of the dialogue was recorded before any animating was done), and the show’s slow-burn storytelling is consistently riveting. As with any good noir, whom you can trust is always in question, and the dialogue is about as on point as banter can get. Better yet, it sticks the landing, wrapping up its swirling set of central mysteries in a finale filled with guts and heart, and with just a touch of the sinister.

.

Sonny Boy

As a society, we tend to think of television as entertainment and not as art, but every once in a while, a series comes around that seems to scream otherwise so loudly even the strongest doubter can’t help but be convinced. Sonny Boy, the first show created by veteran anime director Shingo Natsume, is such a series. Over the course of 12 hallucinatory episodes animated by Madhouse, the students of a middle school stuck between a seemingly infinite array of strange new worlds are forced to ask themselves massive existential questions: What is reality? Do our choices matter? How can we hold on to what is gone from our lives — if it is ever truly gone — and should we? Sonny Boy answers many of these questions with more questions, as its central cast and their fellow castaways either learn to live with their strange new circumstances or fight to escape them in a series that’s as much an exercise in philosophical quandaries as it is in storytelling. It’s a deeply weird show, but that’s the point. Sonny Boy firmly establishes Natsume — an apprentice of Cowboy Bebop creator Shinichirō Watanabe whose past directorial work on such series as One Punch Man and Space Dandy was already exceptionally impressive — as an auteur to watch.

.

The Summit of the Gods

Like the high-climbing feats it gorgeously portrays in muted colors and simple line work, The Summit of the Gods feels inexorably executed — a film striving across its run time to go further and prove its mettle. It mostly succeeds across two story lines that inevitably intersect: Photojournalist Fukamachi Makoto wants to know who first summited Everest, while climber Habu Jôji grows increasingly obsessed with doing just that. We learn more about both of the indefatigable, not always very likable men as they tackle their respective missions, but the film shines on the mountainsides they scale and in the energy that the animators, led by director Patrick Imbert, imbue the climbing sequences with. The characters are designed in clean lines evocative of FX’s Archer, while the background landscapes look grainy by comparison, painted to perfection whether capturing urban environments or the sides of cliffs. Imbert gives all of it the space to breathe, ratcheting up the tension on difficult climbs with deadly precision.

.

Tear Along the Dotted Line

Italian cartoonist Zerocalcare’s claustrophobic adaptation of his own fumetto is a testament both to animation’s sheer limitless possibility and to what creative constraints can produce. Sparse on dialogue but brimming with monologue, nearly the entire series is narrated in voice-over by its anxious, bitter, and struggling cartoonist protagonist, Zero, an epithetic appellation if ever there was one. Throughout, Zero’s meltdowns and memories take remarkable shape and form, not least of which involves the physical manifestation of his conscience as a giant anthropomorphic armadillo with whom he consistently bickers. Imagine the BoJack Horseman entry “Stupid Piece of Shit” stretched across six episodes and you’ll get the idea. All of this would have made for an interesting premise even if the show weren’t about something much bigger than the difficulty of waking up each day within one’s own troubled mind. But the series takes a turn toward the end of its second act, revealing a carefully unspooled central story line that finds Zero and his friends coming to grips with unspeakable loss in a manner sure to leave viewers watching its final moments through tears.

2021

Honorable Mentions

Throughout the year, we maintained a “Best Animation of the Year (So Far)” list. Many of those selections appear in the above top-ten picks; these are the other animated titles that stood out to us this year, presented in alphabetical order.

Angakuksajaujuq: The Shaman’s Apprentice

Canadian Inuit director Zacharias Kunuk’s Inuktitut-language film, rooted in Inuit folklore, is a magnificently eerie stop-motion short with a simple story: A shaman and her apprentice make a house call to a sick man, then visit the underworld to learn why he won’t recover. In its tone and subject matter, the short is reminiscent of Japanese animator Koji Yamamura’s adaptation of Franz Kafka’s A Country Doctor, but in lieu of Yamamura’s exaggerated squash-and-stretch figures, the stop-motion here is subtly cinematic. The visual details are extraordinary — the bright light of sun on snow, the dim glow of a low fire in an igloo, the cold sweat on a sick man’s face, so realistic you can almost smell it through the screen — and the sound design is almost claustrophobic. And while Kunuk’s tale shares A Country Doctor’s fascination with illness, death, and the afterlife, the film’s mythological underpinnings eschew Kafka’s existential alienation in favor of something more spiritually profound, albeit equally perturbing. A gorgeous, unsettling film.

Beastars, Season Two

This prep-school anime gone wild — its protagonists are anthropomorphic animals — is arguably one of the best to hit Netflix in the past couple of years (which is really saying something, considering the streaming service’s investments in the anime space) and inarguably one of its weirdest. The world of this series is one in which carnivores have, by and large, given up eating meat to live alongside herbivores, but the urge to slake their thirst for blood is a hard one to overcome. Is a series whose wolf protagonist pines over a white dwarf rabbit upperclasswoman while trying to unravel the mystery of who ate his friend as his school’s star acting student, a deer, drops out to lead a lion pride specializing in black-market meat sales going to be for everyone? Probably not. Still, the show is compelling because of its strangeness, not in spite of it, and the second season’s doubling down on both its murder mystery and soap-operatic elements is as satisfying as a big, red, juicy steak.

Centaurworld

All-ages, post-apocalyptic found-family fantasies mixing the earnest with the silly and the surprisingly dark have been all the rage in American animation since Adventure Time burst onto the scene in 2010. Centaurworld follows Netflix siblings Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts and She-Ra and the Princesses of Power in that tradition and, at first glance, it threatens to be more of the same. It is decidedly not. The show employs two very different animation styles — one somewhere halfway between She-Ra and The Legend of Korra, the other around the middle mark between Adventure Time and Cow and Chicken — while taking the musical theater leanings of Steven Universe and galloping off with them. The series somehow both serves as the natural endpoint of the past ten years of American animation trends and deliberately sends them up one by one, and it manages more than two tear-jerking showstoppers over its ten-episode first-season run. Also, Tony Hale voices Josh Radnor’s giraffe-centaur’s seemingly sentient flatulence, if that’s your thing.

The Crossing

This oil-paint-on-glass animated feature film has more in common thematically with the gut-wrenching animated war films Funan, Grave of the Fireflies, and Persepolis than the works of paint-on-glass master Alexander Petrov or even 2017’s oil-painted animated feature Loving Vincent with which it shares its visual DNA. It’s a devastating and timely portrayal of child refugees escaping pogroms in an unspecified Eastern European nation, and as the film winds on, the list of their lives’ horrifying turns grows: parental separation, homelessness, human trafficking, the ravages of nature, prison, and seemingly endless loss. The film’s use of bold primary and secondary colors — the bright yellows and reds of protagonist Kyona’s sweater and skirt, the cobalt tattoos on the faces of witches, the greens and purples of circus tents — in strong brush strokes stands out against the drab, watered-down backgrounds of beiges and browns and blacks of the war-torn countryside. The Crossing — co-produced by studios from two of Europe’s historical animation powerhouses, France and the Czech Republic, with a third from Germany — is still on the festival circuit, and not yet available in the States. When it is, it’s worth watching, another powerful war film in a medium not as known for them as it should be.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train

In the first 15 minutes of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train, you will lay eyes on a stunningly beautiful verdant forest and Japanese-style cemetery, charming and colorfully designed lead characters, and a fiery demon carved to pieces by a hyper-detailed magic sword before it explodes in a flash of guts and lava. Like the Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba series it’s based off of, the Demon Slayer movie is as concerned with heart-stopping action as it is with emotive character work and drama, which might explain how it became the top-grossing R-rated movie of all time. Yes, you might be best off watching the show before starting the film, but our advice is to approach that as an opportunity rather than as a chore.

The Ghost and Molly McGee

Disney has a winner in The Ghost and Molly McGee, a buddy comedy starring the relentlessly optimistic titular tween and a crotchety ghost with a heart of gold who haunts the attic of her new home. Showrunners Bill Motz and Bob Roth have been in the Disney stable for years — their first script for the company, in fact, was for Darkwing Duck, way back in 1991. As such, the show borrows bits of tone and design from a number of the Walt Disney Company’s best series over the years, from Gravity Falls to Kim Possible (whose director, Steve Loter, helped produce the series) with a healthy dose of Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends thrown in. Comparisons aside, the show has yet to feel derivative, bringing a light touch to a unique concept, and the chemistry between voiceover veterans Ashly Burch as Molly and Dana Snyder as the ghost, Scratch, is to die for.

Heaven Official’s Blessing

This donghua, about the adventures of a crown prince turned banished god from ancient China and a powerful ghost feared by nearly all other occupants of the heavenly realm, is remarkable for many reasons. The greatest of those is that it is a queer romance from China, a country where LGBTQ rights are consistently under threat and censorship of the arts is fairly common. That in itself would make it worth the watch, especially considering that the series eschews the queer-baiting so familiar to many anime, but Heaven Official’s Blessing has a lot more going for it than just its (beautiful) central romance. It balances action and intrigue with humor effortlessly. It has a robust mythological backstory rooted in Chinese mythology and philosophy that the first season only begins to tease out, which is a rarity in animation that makes it to American audiences. And the animation itself is gorgeous, incorporating the aesthetics of traditional Chinese landscape paintings into an art style that will otherwise be quite familiar to anime viewers Stateside.

Infinity Train, Season 4

You can’t say the writers of Infinity Train were averse to trying new things. With each of its seasons, the animated sci-fi thriller anthology series by Owen Dennis tested the limits of its concept, only to find that the concept was nearly as infinite as its metaphorical engine. The series itself, unfortunately, wasn’t so endless — two seasons after its move from Cartoon Network to HBO Max, someone at WarnerMedia killed the show after deciding that it no longer had “a child entry point.” That seems like corporatese for “it’s not making us money,” but the series had indeed grown more adult and darker by the season. And its fourth season — a commentary on co-dependent relationships that saw the fates of its two protagonists tied together inextricably — is, despite the absence of a heel turn leading to a horrifying death scene, just as dark as its third. While the season’s story arc wasn’t quite as tightly woven as in prior seasons, that seemed to be in part the point: as soon as another person’s life, and struggles, are as important to yours as your own in an unhealthy way, the track to acceptance and self-actualization becomes all the harder to stay on. Is that easy for kids to learn? No. It’s not easy for any of us to learn! Is it a powerful and necessary lesson? Yes. And Infinity Train was powerful and necessary television.

Invincible

Amazon Prime’s animated companion to The Boys engages with ideas familiar to most modern adult superhero fare — power versus responsibility, masculinity run amok, the Übermensch, and on and on — but its execution is where it shines. In the first episode, teenager Mark Grayson learns he has superpowers and is a descendant of an alien race; what he doesn’t know is that his father, Earth’s greatest hero, is a murderous psychopath. Produced by Skybound Entertainment, Invincible is staffed by a flock of superhero animation veterans: character models by Invincible co-creator Cory Walker, storyboards by the likes of the Copeland Brothers (Young Justice, Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts) and Joaquim Dos Santos (The Legend of Korra, Justice League Unlimited), and supervising direction by Jeff Allen (Ultimate Spider-Man, Avengers Assemble, Harley Quinn). Special shout-outs in particular go to the voice casting, direction, and especially the acting. Steven Yeun leads the cast with an anchoring, relatable performance as Mark, while J.K. Simmons flawlessly juggles a nuanced dual role of father figure and fascist liquidator.

Kid Cosmic

Any new series by Craig McCracken, one of American animation’s great design talents and the creator of The Powerpuff Girls and Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends, is a bona fide event in the animation world. But Kid Cosmic ups the ante: As McCracken’s first show for a streaming era, it is also his first serialized series. Kid Cosmic may return to the child superhero trope, but the show is anything but a Powerpuff-style episodic beat-em-up showcase. Patient character development, subtle world-building flourishes, and a willingness to explore just how hard it is to grow up — even with superpowers — makes the series an early standout among 2021’s animation slate.

Maya and the Three

Kinetic and deliriously colorful, Jorge R. Gutiérrez’s Maya and the Three is an all-ages charmer about a young Mesoamerican princess and her fight to save her people. It creatively blends a stop-motion-influenced CGI animation style that makes liberal use of ancient precolonial iconography to narrate a compelling hero’s journey for Maya, the warrior scion of the Teca people. Voiced by a deep bench of talent (Zoe Saldaña, Stephanie Beatriz, Rita Moreno, Gael García Bernal, Alfred Molina, and Danny Trejo are just some of the cast members) and meticulously put together by Tangent Animation, Maya and the Three races through its nine episodes, often literally bursting out of its own aspect ratio for emphasis when the need arises. It’s also clearly made with a love and reverence for “all of Latin America,” in Gutiérrez’s own words, and that means something too.

Megalobox 2: Nomad

Any boxing anime is inevitably going to be compared to the landmark 1970 series Ashita No Joe — which boasts one of the most influential sequences in animation history — and Megalobox, itself based on and created to celebrate the 50th anniversary of that series, is no exception. But Megalobox took its predecessor’s brutal underdog sports story into a grim cyberpunk future set in 21st-century Japan, where fighters don robot exoskeletons in the ring. Megalobox 2: Nomad, the show’s second season, is billed and framed as a stand-alone story, and it departs even further from Joe. The season focuses less and less on the titular boxing and more on the issues inherent to this world, not the least of which are a crumbling capitalist culture blaming immigrants for its problems and the protagonist’s struggle with addiction, loss, and the mistakes of his past. It’s a painful, powerfully told parable for our times but with just enough of a glint of hope — and remarkably beautiful animation to boot.

Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway

Gundam’s latest film is the franchise’s best in at least two decades, even if it’s not exactly intended for newcomers. Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway is functionally a sequel to Char’s Counterattack, the film that closed the book on the conflicts of the original Mobile Suit Gundam series. Like that film, Hathaway is crisply animated and moves at a brisk, politically motivated pace. Its first half’s gunplay and intrigue feel more like watching a James Bond film than a Gundam one (“My name’s Noa, Hathaway Noa,” is how the protagonist introduces himself), and as the first of a planned trilogy, much of it serves as table-setting for a larger conflict. Nonetheless, the film’s major battles excel at dramatizing the dread of watching giant-size robots from the ground, and its warring, mechanized soldiers fly and lumber across the screen with a weight and realism that matches the franchise’s best entries.

Namoo

Animation has no shortage of films and sequences of a life passing bittersweetly in the span of minutes: The opening sequence of Up devastated audiences, and The House of Small Cubes is arguably even more powerful. Oscar-nominated Korean director Erick Oh’s Namoo, from Baobab Studios, is in this vein. The film was created using Quill — a VR animation tool previously bought by Facebook’s Oculus but now back in the hands of its original owners — and depicts the passing of a man’s life through a number of stages of growth and grief. All the while, a single tree grows from sprout to sapling to a mature tree, holding in its branches the detritus of the man’s life experiences. It’s as lovely conceptually as it is visually.

Robin Robin

This holiday entry from Aardman Animations is a charming and literally fuzzy stop-motion story of a robin raised by mice who’s dealing with a character crisis about what exactly she is. Along the way, she gets roped into the schemes of a materialistic magpie, who loves shiny objects and sings through the pipes of Richard E. Grant, and meets a hungry cat voiced by Gillian Anderson. The charm of Robin Robin, directed by Dan Ojari and Mikey Please, is in the details — the warmth of how needle felt was used to create the characters — and the demands of stop-motion mean every movement you see onscreen in a half-hour special had to be meticulously positioned.

Star Wars: Visions

Like The Animatrix two decades before it, Star Wars: Visions never busies itself with selling you on the idea that an anime anthology is a good fit for its Hollywood intellectual property. It just lets the artists show their work, and their work is dazzling. Seven studios created the series’s nine shorts, drawing from influences as diverse as Japan’s chambara films, pop-punk music, and the Star Wars saga itself. The entries’ tones and narratives differ significantly, and never outstay their welcome. Highlights include Kamikaze Douga’s moody black-and-white short “The Duel,” the over-the-top action excess of “The Twins” by the studio Trigger, and Science SARU’s “Akakiri” — a story of seduction to the dark side that puts a grim bow on the whole anthology.

Trese

Netflix’s The Witcher has its anime spinoff film, but if you want something in the same vein, only in TV form, Trese is right there. As rooted in Filipino folklore as The Witcher is in the folklore of Eastern European, Trese splices the monster-of-the-week adventure DNA it shares with The Witcher with the genetic makeup of police procedurals and adds a flashback element to boot. The manner in which it blends these elements and the techniques of serial and episodic storytelling is almost reminiscent of the earliest, and best, seasons of Arrow, back when it was still breaking new ground for superhero TV adaptations. The series is set in contemporary Manila and follows Alexandra Trese, the city’s lakan babaylan, as she attempts to keep the tentative peace between humanity and the supernatural world in a city beset by worldly problems that are just as difficult to solve as those that involve shape-shifting demons. The show depicts a folklore and culture rarely depicted in global media, let alone with nuance. The first season is far too short, clocking in at only six episodes, but that just means there’s more to look forward to.

Tuca & Bertie, Season 2

Adult Swim saving this show from cancellation has already paid off in the episodes screened by critics. Tuca & Bertie more than re-earns its welcome in just a few entries this season, showcasing Tiffany Haddish and Ali Wong’s irreplaceable performances in episodes tackling anxiety, a bachelor/bachelorette weekend, harassment at work, and more. In every episode, the virtuosically stylized animation by the Tornante Company shifts to expose and highlight the pressures and internal tensions afflicting the characters through shifting color palettes, background jokes, and eye-popping movement — demonstrating, just as the first season did, how the medium can be used to represent characters’ interiority.

The Way of the Househusband

This slice-of-life series might pack the most laughs per minute of any series available on traditional television or streaming right now. The show’s episodes are short affairs, hovering between 15 and 20 minutes, and are themselves anthologies comprising a handful of much-shorter vignettes, each of which is centered on a gag related to the show’s consistently hilarious central question: What would happen if a terrifying yakuza gave up the life of crime to become an utterly doting househusband? The answer is simple: It would be kinda scary, kinda funny, and ultimately totally adorable. The animation here is fairly rudimentary (although the illustration packs plenty of detail), but that’s almost beside the point; it feels almost more like a moving comic than an animated show, a technique that seems to draw attention to the material from which it was adapted, Kousuke Oono’s eponymous manga. And the voice acting is pitch perfect. Even those who don’t typically gravitate toward anime will find plenty to giggle at here. You can crush this show’s first season in a little over an hour, and you may well be tempted to, but don’t. It’s worth spreading out the laughs.

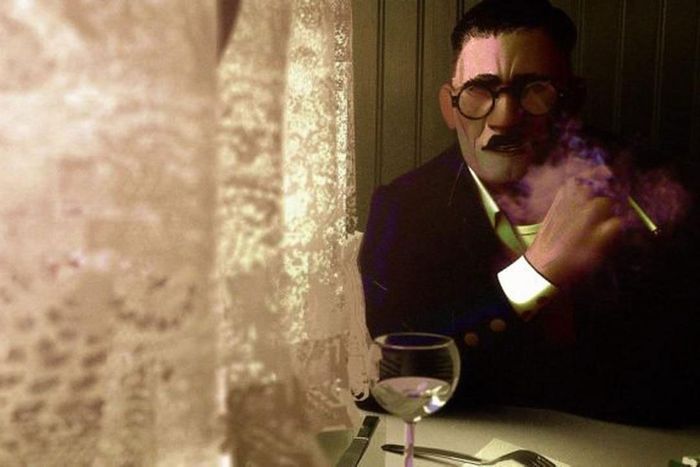

The Windshield Wiper

“Love is a secret society.” That is the conclusion the middle-aged man smoking a full pack of cigarettes alone in a dingy café finds at the end of this powerful short by Alberto Mielgo, after lovers and would-be lovers avoid, disappoint, embrace, and narrowly miss one another in the world around him over the course of just under 15 minutes. CG characters rendered in a style that mimics stop-motion move haltingly over digitally painted backgrounds in a film that meditates on the particularities of love both modern — ghosting via text, matching on a dating app then never following up — and timeless. A powerful outing.

Words Bubble Up Like Soda Pop

“Good-bye is something / like a cherry blossom’s dance / that is never said.” Director Kyōhei Ishiguro, of Your Lie in April fame, would have had a winner with this charming slice-of-life teen romance even had it not asked bigger questions than whether its adorable central characters, Cherry and Smile, would ever get together. And yet it does. Cherry, a poet who is too nervous to speak in public, let alone read his haiku aloud, and Smile, a prominent social-media personality who hides her braces-laden buckteeth behind a surgical mask (talk about timely), reckon with their own insecurities as much as their budding romance, and their central quest for an elderly widower’s lost album of his late musician wife’s only recording is a moving exploration of love, loss, and what it means to come to terms with both. The brightly colored Pop Art–inspired visuals instill the film’s suburban setting, centered on a shopping mall, with a sense of life that’s not quite as powerful as Makoto Shinkai’s your name., but it begs to be a similar sort of crossover hit with western audiences. Oh, and the soundtrack bops.

Young Justice: Phantoms

Greg Weisman and Brandon Vietti’s grand take on the Teen Titans family of superhero sidekicks has returned for another season and has fully evolved into “What if Robin’s friends were dealing with Game of Thrones plots every week?” To be clear, that’s a compliment. In just a few episodes this season, its heroes had to endure several cosmic layers of historical daddy issues, a fraught royal wedding, a major character’s death, and interplanetary scheming that would make Littlefinger cringe. But this makes it one of the most excitingly watchable superhero shows in any format.

If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.

More From This Series

- What’s the Most Memorable TV Moment of 2021?

- The Best TV Trees of 2021

- The First Annual Golden Dolly Awards