This was a big year in bookworld for the phrase “much-anticipated.” As publishers reinstated some semblance of normalcy after pandemic shipping delays, a bevy of marquee names beckoned readers with long-awaited follow-ups — and, in some cases, unexpected merch. The heavy hitters met with mixed success, but this year was still abundant with books that scribbled outside the lines, upended old conventions or freshened them up, and dug out stories we’d forgotten or never known to ask about. The best of the lot were invigorating — the kinds of books that crawl outside their text and into your life. And, of course, there was a new Franzen novel.

10.

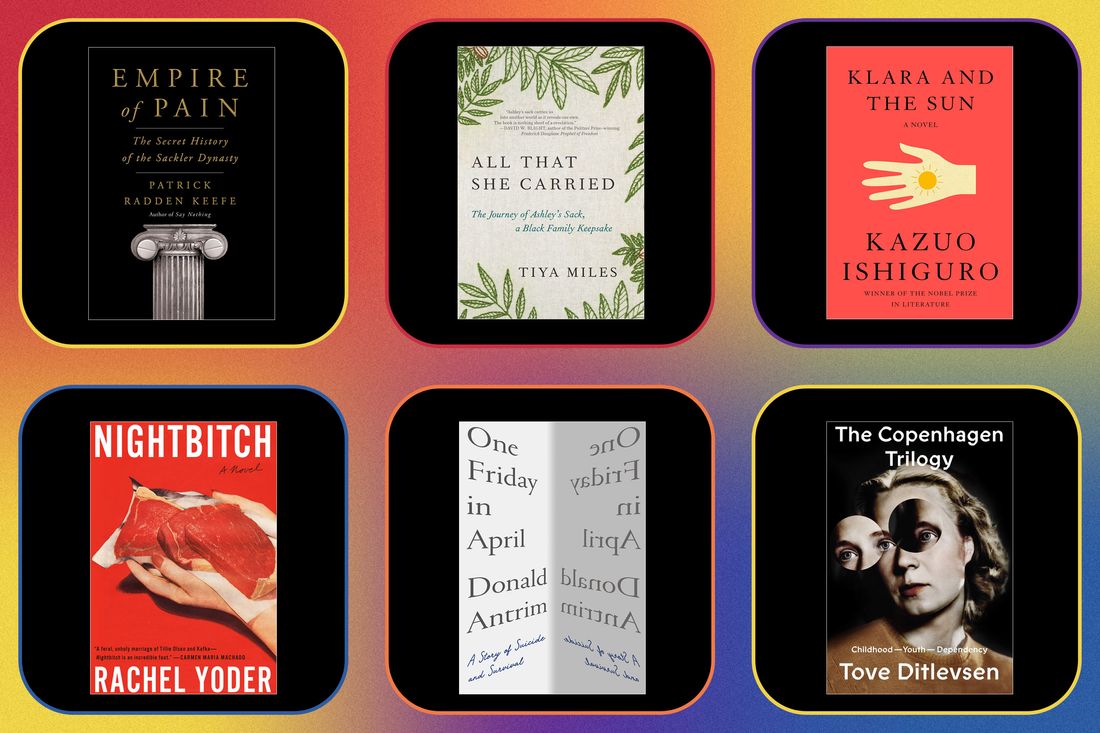

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

This story of a resentful artist turned stay-at-home mom morphing into a dog claws its way out of the pile. Yes, the premise sounds a bit like it was found on the reject list at a B-movie studio, but Yoder’s commitment to describing the animal nature of parenting carries it through with maximal success. The protagonist grows a scruff of coarse hair above her sacrum and sniffs out bunnies in her yard; playtime with her son involves licking and biting. Her metamorphosis is a “a pure, throbbing state” that redirects her energy and moves her beyond learned helplessness. Yoder goes deep on the performative nature of mothering — how so much of it feels like a Marina Abramović performance in which strange creatures are invited to scream in our ears and wrestle raisins from our fuzzy pockets, all while we gaze ahead coolly. In a crowded field of novel-manifestos about the indignity of parenting, Nightbitch is primal and corporeal, a labor scream of a book.

9.

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen

Translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman

For months this was my pitch to potential readers of The Copenhagen Trilogy: “You have to read this. It was so good I couldn’t finish it.” Blame my low tolerance for inhabiting someone else’s psychosis. These books percolate with the sickening anxiety of madness, a state that the best writers can render as a kind of hell. From her muffled young adulthood in Nazi-occupied Denmark to her rise as a writing wunderkind and spin into a romantically mangled, drug-fueled early adulthood, Ditlevsen’s autobiographical collection (composed of three formerly separate memoirs — Childhood, Youth, and Dependency — first published between 1967 and ’71) spares neither the writer nor the reader. This is not a tale of heroic endurance. It’s a sally inside the mind of a young writer who tentatively climbs toward professional success and familial stability, only to find that both are moving targets.

8.

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles

The stories of enslaved Black Americans are still far too scarce, lost to time by a nation indifferent to more personal aspects of the experience. Miles, a Harvard historian and MacArthur fellow, had little definitive information about a simple embroidered sack found at a flea market in 2007, other than what it said: My great grandmother Rose mother of Ashley gave her this sack when she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina / it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her It be filled with my Love always / she never saw her again / Ashley is my grandmother / Ruth Middleton / 1921

From there, she traces the likely lineage of this unlikely object — a bit of cotton that might have crumpled into dust, but instead carried a whole family’s legacy — and puts both what she learned and what might have been into this riveting book, which just won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. All That She Carried balances two aims: to share what it can of Ruth Middleton’s matrilineal family and to explore what their lives might tell us about the experiences of other Black women connected, thread by thread, to an uncertain past. The result is as delicate and determined as the story that inspired it.

7.

I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

Forget reading for comfort. Watkins has no interest in the concept, for herself or for you. I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness follows a protagonist (also named Claire Vaye Watkins) who leaves her family behind as she smokes and ruminates and screws her way through the Mojave Desert, where she grew up. The story alternates with real (but edited) letters written by Watkins’s mother as a teenager and excerpts from Watkins’s father’s book about his role as Charles Manson’s “number one procurer of young girls.” The desert setting is as prickly and vast and mutable as Watkins’s writing; the book is a stern kick to the groin of heroic tales about the majesty of the American West. Watkins wrote two brilliant books before this — the otherworldly good story collection Battleborn and a terrifying enviro-novel, Gold Fame Citrus — but this is the work that should put her on the map. Watkins is a necessary writer for a changing American pastoral.

6.

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe

For the first time, the U.S. has surpassed 100,000 deaths from drug overdoses in a single year — and opioid deaths accounted for more than 75 percent of those. Opioid overdose has grown so common that some cities have installed Narcan vending machines and pharmacies put up posters showing customers how to administer it. The epidemic has spilled into every corner of American life. In Radden Keefe’s meticulously reported and brilliantly assembled Empire of Pain, he traces that spill back to the family at the very center: the billionaire Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma. Like Gilded Age barons before them, the Sacklers sat atop a massive fortune, behind a fortress of lawyers and corporate privacy screens, while their company pushed OxyContin onto prescription pads and out into America. It’s a blood-boiling story of American apathy — of a family more concerned with putting their name on museums than keeping people from harm, a pharmaceutical industry shrugging its shoulders at staggering death rates, and a medical community entirely unequipped to handle the surge.

5.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

In the very near future, an AF (Artificial Friend) named Klara, manufactured as a companion for a child, stands in the sunlit window of a quiet shop and narrates her yearning to be purchased and taken home. She’s childlike herself and exceptionally naïve; we are immediately endeared to her, though we know her insides are wire, her thoughts determined by code. Ishiguro has claimed his prose is nothing special, but over the course of his career, he has again and again managed to push readers into mourning for some of the most isolated members of society. Klara and the Sun glides in on tiptoe, tracing delicate circles around Klara’s time in the shop; her life with Josie, the young girl who takes her home; and the realization that Josie’s mother’s decision to genetically “lift” her daughter’s intelligence is costing the girl a normal life. Even in the book’s quietest moments, there’s a sense that humanity’s control over itself is on the line. And much like Ishiguro’s earlier book Never Let Me Go, this novel delivers a tender, enthralling twist.

4.

Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir by Akwaeke Emezi

Sometimes a writer comes along who seems to float above language and direct it like a sorcerer, raising up whole worlds then sliding them out of the way. That’s Emezi. Dear Senthuran is their fourth book in three years (with another three on the way), and they organize this memoir — about their childhood in Nigeria; their role as an ogbanje, which they describe as a spirit reborn to cause suffering; and their painful, necessary gender-confirmation surgeries — as a series of letters to friends and family, a form that amps up the intimacy and penetration of the work. Emezi’s words emerge, bold and annunciatory.

3.

One Friday in April: A Story of Suicide and Survival by Donald Antrim

One Friday in April 2006, Antrim checked himself into the psychiatric facility at Columbia Presbyterian; late that summer he finally exited its doors, after several new medications had failed and innumerable group- and individual-therapy sessions, as well as about a dozen rounds of electroshock treatments that made it possible for him to at least “look forward to feeling well.” His memoir about the experience ought to immediately join the pantheon of classic works about the treacherous pull between life and death that can occur in one person’s mind. Antrim cracks himself wide open. The book is declarative and urgent, tracing the precise contours of suicidal thinking; it’s also quiet and engineered, a fully reasoned tour of a recalcitrant brain. “Maybe you’ve spent some time trying every day not to die, out on your own somewhere,” Antrim writes. “Maybe that effort has become your work in life.” One Friday in April may be remembered as the work of his own.

2.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

I started the year thinking that Lockwood’s pseudo-autobiographical bait and switch irritated me too much to ever wiggle its way onto a list of my favorites. Then the damn thing crawled inside my head and refused to leave. If this sounds like the opposite of an endorsement for this book — which begins as a story about the noxious pull of the Twitterverse and turns into a family drama — that’s because when I first encountered it, I felt primed to reject a novel propelled by social-media discourse. (“The word toxic had been anointed, and now could not go back to being a regular word,” Lockwood writes. “It was like a person becoming famous. They would never have a normal lunch again, would never eat a Cobb salad outdoors without tasting the full awareness of what they were. Toxic. Labor. Discourse. Normalize.”) Here’s what’s kept me bouncing back to it: Lockwood doesn’t give a shit about the traditional novel or what anyone might want from it. She knows she can nab you with descriptions of the self-imposed suffocation of being Very Online before wringing your heart out with the tale of a dying infant. No One Is Talking About This flicks the Establishment in the face and giggles.

1.

Matrix by Lauren Groff

I wanted to live inside this novel, to peel apples and dig in the soil and repair the stone walls of the nunnery Groff manifests as she builds a life around Marie de France, the 12th-century poet and maybe-abbess about whom we know very little. And what a life Groff designs, unfurling Marie’s story in ribbons. Big, awkward, and of mildly noble heritage, the teenager is cast out of the French royal court by Eleanor of Aquitaine, whom she adores, and sent to starve in a dripping, tumbledown convent. But through sheer grit and wildly progressive plans, she spends the next decades turning the abbey into a paradise for women — a sheltered place where their work has meaning and their faith can catapult beyond unthinking ritual. Matrix practically draws blood in its bid to evince ecstasy, physical, spiritual, and emotional. This novel has its own racing heartbeat.

Honorable Mentions

Throughout 2021, I maintained a “Best Books of the Year (So Far)” list. Many of those selections appear above in my top 10 picks. Below are the rest of the books that stood out to me this year:

The bloody pyrotechnics of anti-abortion organizations in the early ’90s, country-club drunks and their cruel domestic antics, the pre-internet teen scene in Buffalo: Jessica Winter’s sophomore novel is Franzen-esque in its broad sweep of a Rust Belt family coming down off the highs of mid-century American capitalism. (I say that as a huge compliment.) Winter starts with Jane Brennan’s accidental pregnancy in the late 1970s, then works through her tempestuous relationship with her shotgun husband and the push-and-pull dynamic with her eldest daughter Lauren, and finally into the utter displacement the Brennan family undergoes when Jane brings home Mirela, one of hundreds of thousands of “Ceausescu’s children” — Romanian children abandoned in orphanages in poor living conditions. Like Graham Greene before her, Winter is fascinated by the Catholic draw to suffering — Jane’s as a beleaguered mother, Lauren’s as a misunderstood young woman, and Mirela’s as a nearly feral outsider — and she manages to elegantly and movingly write a novel about faith that doesn’t proselytize or condemn.

Greenidge debuted with a bang in 2016 with her novel We Love You, Charlie Freeman, about a Black family who agrees to participate in a psychological study more nefarious than it first seems. Libertie is a tamer work, though no less forceful and imaginative. Libertie is the dark-skinned, free-born daughter of a light-skinned doctor mother in Civil War–era Brooklyn. The story begins when an enslaved man named Ben Daisy is delivered to them in a coffin — alive. From there, Greenidge charts Libertie’s development from college student to young wife, and then stranger among family in Haiti, wondering where she belongs and whether she belongs to someone. Every bit of Libertie is rich and vibrant, offering the best of what historical fiction can do.

America isn’t paradise, one of Engel’s characters thinks to herself in this tale of a cleaved immigrant family. Co-workers murder each other with semi-automatics, kids blow each other’s brains out at school. And violence isn’t held at bay by ICE; in fact, it’s often perpetuated by the people who fill the agency’s ranks. Infinite Country follows whats happens when one member of an undocumented Colombian family is deported. Engel writes beyond mere frustration or sadness or economic hardship — and she brings individuality to a story too often told in statistics and two-minute news reports.

Reading this novel is like holding a live wire in your hand. The first novel by a trans woman to be nominated for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, it follows a triangle of people — Reese, a trans woman desperate to be a mother; her ex Ames (formerly Amy), who detransitioned and is living as a man again; and Ames’s boss Katrina, who is pregnant with his child and unsure about the prospect. But there is so much more than that — Detransition, Baby is populated like a Dickens village of the queer community, with married HIV-positive cowboys and IVF-entangled trans couples. Most refreshingly, it isn’t out to prove that a trans love triangle can move copies just as affectively as cis ones do; there’s no mimicry here. It is what it is, an eyes-wide-open escapade.

In this mash-up of culinary history, cultural criticism, and memoir, the cookbook author and essayist chooses a different “difficult” fruit for every letter of the alphabet — things like authentic maraschino cherries made with poisonous bitter almond juice, little-known thimbleberry, inedible Osage orange. Some entries are almost entirely personal histories, but most move around more freely — like a chapter on juniper berries’ unwritten history as an abortifacient, or the story of the eugenicist horticulturist who domesticated blackberries for the masses. Through it all, you can connect the dots on humanity’s history of turning fruits into magical entities capable of tightening our skin, supercharging our diets, and making sense of evil in the world.

Nadia Owusu’s young life was splintered into dozens of little pieces — her Armenian American mother left the family, her sometimes cruel stepmother joined it, and she moved between continents for her father’s work for the United Nations. Her memoir Aftershocks, structured as a series of reverberations, doesn’t assemble those bits together. “I have written for meaning rather than order,” she explains. She whisks together the fractured history of her father’s homeland of Ghana and her own privileged bubble inside sometimes bomb-strewn locales, then teaches herself to reread her own childhood history, to see beyond the story she has always told herself of who she is.

Cornflower blue, Simpsons-esque skies may be a thing of the past if the environmental scientists get their way. In Under a White Sky, the Pulitzer-winning Kolbert examines — in terrifying detail — the measures researchers and climatologists have already taken (like electrifying the waters of the Chicago River so invasive Asian carp can’t make their way to other tributaries) or are considering (filling the atmosphere with light-reflecting particles to form a sunshield and, in turn, a powdery firmament) to reverse-engineer the ecological mess humanity has gotten itself into. This is definitely an “It’s Time to Worry” book, but it’s also a wise rumination on hubris — how factories and engines and our desire for Progress set a ticking time bomb on our planet, and how mankind now thinks it can mastermind a way to cut the fuse.

Forgive me for screaming, but In the Quick is Jane Eyre IN SPACE! The idea sounds unhinged, but its execution is so fresh and so understanding of Brontë and genre fiction that it all comes together in a wild Ad Astra meets Prep mash-up. In a not-so-distant America, orphaned young June Reed is sent to study at the space program her brilliant uncle founded after his early death. At the same time, a crew he sent deep into the solar system suddenly goes quiet. As June endures a punishing regimen of robotic sciences, physical fitness, and team-building exercises, she quietly works on the problem of where the crew might be and how best to save them. An entirely fun adventure.

Lately I’ve been missing the sweaty rub of strangers’ arms in tight city streets and the faint smell of yeast rising up from bar floorboards. Cities are made for clamor and bustle, and the past year has emptied them of both. Mozley’s Hot Stew is just the sensorial knockout I needed, alive with the hoots and steam of a small patch of London’s Soho, where an unlikely group of tenants works to keep their building, a French restaurant with a brothel on top, out of a developer’s grip. Among the tenants are a sex worker and her carer, a homeless couple who inhabit the grates beneath the building, a policewoman, and a bright young thing — a mix just as chaotic as any group of strangers sharing walls and air in the city’s bowels. Mozley writes across the spectrum of humanity — a talented juggler who throws a dozen plates in the air and then catches each one as if it were nothing.

A biography that intentionally blows up its subject’s own image. On the cover: A demure Helen Frankenthaler neatly seated on one of her pastel-soaked canvases in a salmon-pink button-down that could blend right in with the paint, a dainty cream headband holding back her Veronica Lake curls. Inside: A rollicking beat-by-beat saunter through the downtown 1950s art scene and a long-overdue reckoning with Frankenthaler’s oft-derided, so-called “feminine” work. Too pretty, too rich, too well-connected — these were the bombs lobbed at Frankenthaler even after she produced Mountains and Sea, the seemingly brushstroke-free, nursery-colored work that Nemerov claims launched the genre of color field painting. Nemerov admits to his subject’s privileges, but undoes the (jealousy-induced) fantasy that Helen, as he calls her, was just a painter of pretty little pictures. This Helen is a woman of the mind, a crucial component of America’s mid-century dominance in the art world, and, at times, a provocateur, even if she didn’t see it that way.

Give me the glorious tangle of page-long sentences, the piled-up cacophony of crowded prose. In Painting Time, French novelist de Kerangal (she whose book covers always lure me in) refuses to match form to subject matter, a collision that yields a stylistic wildness we need more of. Protagonist Paula Karst is a young Parisian decorative painter learning trompe l’oeil, “the art of illusion,” at an intense Belgian institute that churns out faux marble re-creators and faux bois conjurers, but not artists. Formerly a glassy-eyed layabout, decorative painting has molded Paula into a rigorous worker, and Painting Time accompanies her through that transformation. As she moves from Paris to Moscow to Rome and back again, it’s de Kerangal’s meticulous understanding of the tiny devotions that craftspeople make again and again — the thin strokes, the blended edges, the changing of brushes — that elevates Painting Time into a pulsing ode to creative labor.

The first time I heard about ACT UP — the organization that formed to demand that the political establishment and scientific community take action on AIDS — was nine years after it was founded, when activist David Reid poured the ashes of a friend who’d died of the disease onto the White House lawn in 1996. “If you won’t come to the funeral,” he said, “we’ll bring the funeral to you.” The act was shocking to my 12-year-old self, but it’s not nearly as shocking as the history of neglect, contempt, and disgust for the gay community that thinker, archivist, and ACT UP activist Sarah Schulman writes about in Let the Record Show, a necessarily expansive and bombastic corrective of modern history. Using years of interviews and her own vast inside knowledge (the Times’ Parul Sehgal called Schulman “a living archive”), Schulman charts ACT UP’s highly effective barricade-storming tactics, eventual sway over drug companies, and early ’90s fracture. Let the Record Show is as righteous and revelatory as its subject matter.

I counted over 130 exclamation points in Second Place, Rachel Cusk’s first novel since the end of her highly celebrated, much-dissected Outline trilogy. For Cusk, well-known for her tight control over her prose, such bluster and exuberance demonstrate a more unwieldy new direction, an experimental phase. Protagonist M is the bombastic exclamation-point user, as she writes a letter to a friend about her miserable experience hosting L, a famed painter of the Lucian Freud variety, at her home in an English marsh. Seeing L’s work once helped to transform M’s life, and she hopes his presence will provoke another revelation. Second Place grapples with the contradictory desire to be muse and artist, and with the extraordinary tolerance that the world shows intolerable men.

In the first scene of Good Behaviour, originally published in 1981 and reissued in May by the reliable folks at NYRB Classics, protagonist Aroon St. Charles kills her mother with the mere scent of a rabbit mousse. She puts the lunch tray in front of her, and Mummy trembles, cries, vomits, and promptly dies in “a nest of pretty pillows.” Is it intentional? Why no, not exactly, but it is a glorious introduction to this novel with a hungry, wolfish smile but no visible claws. Aroon is a child of the Irish aristocracy, raised in the early 20th century in a manse built by her ancestors; she’s bent on explaining her good intentions to the reader, though she seemingly understands very little of her own motivations. This is not a damp, woe-is-the-child redux: Good Behaviour includes very little good behavior, featuring instead delicious and deleterious accounts of illicit sex and wild high jinks, and a mother-daughter duo who can scrap with the best of them.

Witch hunt! The phrase has enjoyed a renaissance, courtesy of our former POTUS, along with MeToo-ed men of all varieties. It reverts to its original meaning in this romp, from the cerebral and daring novelist and essayist Rivka Galchen, that’s set in 17th-century Germany, a time and place where women were hunted, jailed, taunted, and tortured for actually (supposedly) being witches. Galchen’s novel focuses on illiterate but brilliant Katharina Kepler — a real historical figure and the mother of the iconic astronomer Johannes Kepler — as her neighbors turn against her, bringing wild charges of hexing and poisoning. This parable about the dangers of many little lies is also a true guffawer, with a protagonist so sharp and self-righteous she may have a direct familial line to Olive Kitteridge. Read it to leave this century behind for a while.

All of Taylor’s stories of young midwestern ennui are A sides, but one tale from this new collection, “Anne of Cleves,” is particularly bound-for-the-anthologies good. Sigrid is on her first date with Martha when she asks her with which wife of Henry VIII she most identifies. Martha is an engineer, living outside the shimmery dome of the liberal arts, and she barely understands the question. But it reverberates underneath their whole relationship; for the next 30 pages, the two women slide toward one another and then away in a mating dance reminiscent of a Shirley Hazzard story, where sighs and shifting thighs make huge waves. And yes, Martha is an Anne of Cleves: strong, stoic, and capable of survival. Taylor’s energy is so focused, his characters so full and motley, that each of the 11 tales here (some of which are linked) fleshes out a small spinning world of its own.

Katie Kitamura’s novels are like recently vacated rooms. The occupant’s scent is still there, the warmth of their hand on the doorknob, but the space itself is desolate. Intimacies is the story of an interpreter for an international court in The Hague who is lingering in an in-between space of her own — she cannot pin down her Dutch boyfriend, who moves between her and his estranged wife, or the charismatic, recently deposed African president whose words she worriedly translates as he stands trial at the court for crimes against humanity. Is she misreading everyone and everything in her adopted country? Is there a reason for her to feel this low-level dread? Like Muriel Spark in her darker moments, Kitamura taps into the most basic human fear: that we will never really know anyone.

Kleeman doesn’t do maudlin — she forces you to look into the fun-house mirror until you realize that what you’re seeing is reality. Something New Under the Sun starts off as a Hollywood send-up, when a novelist arrives on the set of a film adaptation of his work and discovers he’s actually a babysitter for the tabloid-ravaged teen bopster playing the lead. He also realizes he’s in a hellscape where water is scarce, a commodity for the yacht set, and WAT-R — a molecular near copy of the real stuff — is pumping out of every other faucet and plastic bottle in California. Because this is Kleeman, the plot is far less important than the view along the way. Her writing is cool, detached, and DeLillo-ish, the urgency red hot. Reading it while the West crackles, it’s easy to imagine this book may someday be a vital artifact from our era of climate twilight.

The British press has been singing the praises of Wilson’s wise, brutally honest, expansive consideration of Lawrence’s “middle years” — the time from 1915 to 1925 when he wrote Women in Love and The Rainbow, exiled himself from England, and tried to found a utopian community in New Mexico. American readers haven’t picked up on it yet, but it’s time to change that! For all the hoo-ha that once surrounded his reputation and antics, Lawrence is now considered a sturdy, capital-I Important writer. Nonetheless, his novels don’t make it to syllabi, and his life hasn’t been called up for a feverish prestige biopic. Wilson writes without undue flattery or inflation about this decade of Lawrence’s life, when he was convicted of spying for Germany and darted across America to meet a mildly mad heiress and produced some of the century’s most enduring novels. This is a biography on fire, brilliant with tiny anecdotes and broad assertions about English literature alike.

Whitehead knows how to slither into a new literary identity with perfect ease. He started his career writing magic-sprinkled novels about zombies, elevator-repair workers, and John Henry before publishing The Underground Railroad in 2016 and The Nickel Boys in 2019, both investigations of cruelty inflicted upon Black Americans. These books became runaway hits of the change-the-author’s-life variety. How to switch things up again? Harlem Shuffle is a zooming, maniacal caper; the fact that it’s wrapped up in a historical novel is a sweet little bonus. There’s too much (read: just enough) plot for one sentence to do it justice, but let’s leave things here: A scheme by a madcap cast of characters to rob a swanky uptown hotel canters alongside a potent reconstruction of mid-century Harlem’s buoyant vibes.

Liselle is a private-school teacher in a tony Philadelphia neighborhood; her lawyer husband, Winn, just lost an election for state representative, and the FBI is investigating him for his campaign’s behavior. Set around a dinner party Liselle is reluctantly hosting, Solomon’s insightful The Days of Afrekete dives back and forth between Liselle’s cracking veneer and her memories of an intoxicating relationship (with the brilliant, unconventional Selena) that once constituted her world. It’s in the nitty-gritty that Solomon nails things — Liselle’s fretting over whether financial success has recast her as an out-of-touch Black woman; the rightfully chaotic depictions of sexually ambiguous entanglements. The publisher describes The Days of Afrekete as Sula plus Mrs. Dalloway; Toni Morrison and Virginia Woolf may be towering names to live up to, but Solomon is on the right track.

The Lucy Barton universe keeps expanding. Strout published My Name Is Lucy Barton, the gentle blockbuster introducing the character, in 2016, then broadened the web with the interconnected stories in Anything Is Possible, set in Lucy’s quiet Illinois hometown. Now Strout has written a more linear follow-up with Oh William!, which takes place about 20 years after the events of the first book and sees Lucy widowed and reconnecting with her first husband, the titular William. Strout’s placid prose and unswerving style go down as easily as ever. In other hands, this novel might reek of franchise aspirations, but the Pulitzer-winning author remains as devoted as ever to storytelling that prods at life’s big questions about trauma, loneliness, and the search for a hand to hold in the dark.

More From This Series

- What’s the Most Memorable TV Moment of 2021?

- The Best TV Trees of 2021

- The First Annual Golden Dolly Awards