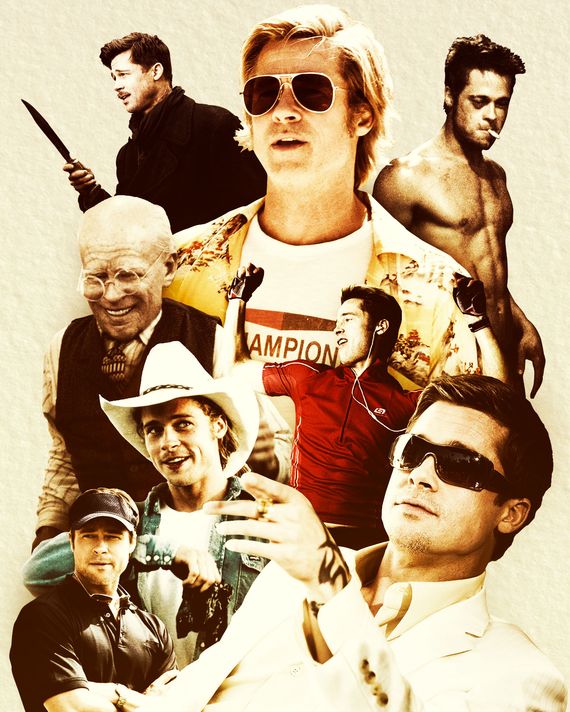

Brad Pitt is undeniably a great movie star. He has an enviable coolness that snakes through his work onscreen, most recently used to great effect in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. He’s the kind of movie star that has become increasingly rare — larger than life, assured, contradictory, physically mesmerizing, with a strong understanding of the power of persona. But is he a great actor? This question is trickier to answer because of the scope of his career and how subtle his best work can be.

Pitt’s decisions as an actor betray a curiosity I’ve always found admirable. One of the most perceptive insights into his work comes at the end of Jeanine Basinger’s trenchant book, The Star Machine. As Basinger writes, “Many of [his] ‘safer’ choices have actually been among the worst failures of Pitt’s career. Seven and Fight Club, by contrast, were huge hits. Pitt is thus one of the few neo-stars whose persona is located in, rather than denied by, his edgier projects.” Indeed, Pitt dazzled in his collaborations with David Fincher as the hotshot young detective in Seven and the enigma Tyler Durden in Fight Club. Despite his looks and presence, he makes a poor matinee idol. In films like 2016’s Allied, he seems bored with playing the stock dashing American hero. He’s also not the kind of actor who tries to prove his mettle by making the labor of acting visible through tortuous realism (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Oscar-nabbing turn in The Revenant) or by obscuring his beauty (Christian Bale, in everything since American Psycho; Jake Gyllenhaal in Nightcrawler). Pitt instead has a tremendous understanding and use of his body. As Elaine Lui wrote on Lainey Gossip, “As it is with all true Movie Stars, Brad Pitt’s face is a full body experience. He actually doesn’t get enough credit for the way he uses his body as an extension of his face.” His work in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is being recognized for this very reason: His physicality speaks fully to a character’s history and portrays a remarkable self-possession.

What has held him back has been his lack of consistency. This was more pronounced in the 1990s, when he ricocheted from great works like Kalifornia, as the lurching menace Early Grayce (which Roger Ebert called one of the most “harrowing and convincing performances” he’d ever seen) to straight-up middling work, sporting a wavering accent in The Devil’s Own. But in recent years, Pitt has been doing the most consistently interesting work of his career, in roles when his coolness is pushed to its limits and his characters find they can no longer run from the emotions they’ve kept hidden away. He’s best at the pitch of contradiction: when his self-possession clashes with his rage, loneliness, and masculinity.

This awards season alone has seen Pitt do career-best work in two very different performances — from the cocksure grace and bloody violence of Cliff Booth in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood to the tender yearning of Roy McBride in Ad Astra. I am especially haunted by his work in the latter, which is one of the most piercing depictions of what patriarchal conditioning does to men I’ve ever seen. Each performance speaks with eloquent precision about masculinity — how it’s shaped this country, its relationship to violence, and how men compartmentalize emotions. Pitt, who has just received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor, said in a recent New York Times profile that he’d be acting less going forward. Given these performances, I think he still has so much more to say.

44. Happy Together (1989)

Happy Together is a mostly forgettable romantic comedy in which Pitt plays Brian, a college student seen at parties and in lead Patrick Dempsey’s acting class. It’s too slight a role to be memorable, and it doesn’t ask much of Pitt either.

43. Cutting Class (1989)

In this sloppy high-school slasher flick, Pitt plays Dwight, a basketball star, academic slacker, and jealous boyfriend. Sadly for Pitt, Dwight is a poorly sketched archetype rather than a living, breathing character. Pitt’s charisma is evident, but it isn’t enough to flesh out the role or give audiences something to hold onto. There’s also a hesitancy to his performance that lessens the impact of his charm.

42. Across the Tracks (1991)

A staid, flatly shot drama about two brothers on radically different paths; Pitt plays the golden boy, a track and field star aiming for a Stanford University scholarship. As with his other early roles, he comes across as stilted and stiff, not yet used to what the camera requires for a believable performance.

41. The Dark Side of the Sun (1988)

After uncredited turns in four films, Pitt’s first starring role in this 1988 Yugoslavian-American production was shelved and not released until the late 1990s. Pitt plays Rick, a young man with a rare skin disease that prohibits him from being in the light, so he goes around wearing head-to-toe leather. This includes wearing a mask that makes him look like a strange fetish object, making his performance pretty weird until 35 minutes into the film, when we finally see his face. Pitt’s skills are unrefined here; he feels roughly sketched, even performative, as he charts the childlike exuberance and yearning of his character.

40. Johnny Suede (1991)

I can’t fully put my finger on what this Tom DiCillo–directed independent film or Pitt’s performance as aspiring musician Johnny Suede is going for. Whatever it is, it doesn’t work. Pitt seems strangely indecisive about every choice he makes, whether it’s staring down a white-haired Nick Cave or reacting to his paramour as she explains that she’s in an abusive relationship. He’s unable to grant the character any sense of an interior life. Johnny Suede is evidence that even great stars, the ones we associate with lightning-bright charisma and grace, can take time to hone these qualities and effectively communicate them to the camera.

39. The Favor (1994)

The Favor, filmed in 1990 before Pitt’s star-making turn in Thelma & Louise, but shelved until 1994, is a desperate blend of styles and tonalities. It’s the kind of film that has to be seen to be believed. The movie centers on a housewife in a somewhat passionless marriage who convinces her best friend Emily to sleep with her old high-school love so that she can vicariously experience the affair. Pitt isn’t the flame in question — he’s Emily’s lover, a young artist who primarily functions as a sex object to be gawked at and throw a hitch in the movie’s insane plan. Pitt maintains a dopey yet forthright quality that cuts through the ridiculousness of the film, but what’s most fascinating about the role is witnessing his familiar gestures — broadly open arms, fingers to his lips in concentration — without the impact they’d gain later.

38. Cool World (1992)

Ralph Bakshi’s lurid, grating live action/animation hybrid, created in the wake of Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s success, does no favors for its actors. As Roger Ebert noted in his review of the film, “In Cool World, a human character will throw an arm around the shoulders of a cartoon, and the mismatch will be so distracting it’s the only thing we can look at on the screen.” As a 1940s-styled gumshoe policing the animated landscape of Cool World, Frank Harris (Pitt) doesn’t have much of an arc. His performance is ultimately stiff and unimaginative. Pitt himself seems to agree. In the August 1992 issue of Details, this is how he summed up his Cool World experience: “It was fun. But I got into some bad habits because I did most of the film by myself. Behind a blue screen, you know? Acting’s magical when it’s fresh. Someone throws something your way, and you catch it and you throw it back. It’s hard to be impulsive when you’re working with a blue screen.”

37. Sleepers (1996)

A starkly moralistic drama charting the lives of a group of friends raised in Hell’s Kitchen, including their abuse in juvenile detention and their quest for revenge as adults. Pitt plays one of the friends, Michael, who as an adult has become an assistant district attorney. It’s far from his best work. Pitt dips in and out of an uneven accent and struggles to convey the weight of a man haunted by deep childhood trauma.

36. The Devil’s Own (1997)

The Devil’s Own is a muddled bore of a film in which Pitt plays a member of the Irish Republican Army who goes undercover in America to buy missiles he hopes will aid his cause. Pitt has never been a transformative actor in the modern sense, where we equate Good Acting with weight lost and gained, difficult accents, and de-glamorizing. His best work often is in more nuanced explorations of the calm, fully Americana persona he’s constructed. The Devil’s Own isn’t one of them. In the film, Pitt sports a rural Irish accent that renders him mush-mouthed. But the accent is only part of the problem. The Devil’s Own had a difficult production. “Ego clashes, budget overruns and long delays plagued the project,” as reported in the New York Times at the time. Pitt at one point said it was “the most irresponsible bit of film making — if you can even call it that — that I’ve ever seen.”

35. Seven Years in Tibet (1997)

Seven Years in Tibet — the autobiographical drama adapted from the novel of the same name by Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, set against the backdrops of World War II and the 1950 invasion of Tibet — demonstrates the worst traits of Pitt as an actor in the 1990s. Distracting accent? Check. Strange blankness in moments as if nothing is going on behind his eyes? Check. Harrer may have led an interesting life, but in Pitt’s hands, he’s all surface-level characterization. He seems more focused on the accent than imbuing his character with an interior life. I can see why Pitt would be drawn to a sweeping historical war drama to prove his mettle, but he only looks the part of a dashing, selfish adventurer. When it comes to portraying the reality of who that person is, he falls short.

34. World War Z (2013)

Nearly everything about this apocalyptic zombie flick slips from your mind the moment it leaves the screen, including Pitt’s rote performance. He struggles to, well, bring life to the character of Gerry Lane, a U.N. employee trying to keep his family safe as the zombie crisis spreads. Matt Zoller Seitz puts it well in his review: “He’s every other character played by Robert Redford in the 1970s and ‘80s: noble, brave, calm in a crisis, endlessly resourceful, kind to his spouse and children, respectful of authority but not slavishly so, independent-minded but not arrogant; a snooze.”

33. Meet Joe Black (1998)

Meet Joe Black is truly one of the most bonkers romance films of the modern era. When we first meet Pitt, his charm is off the charts as he flirts with Susan Parrish (Claire Forlani)… before getting into a brutal accident where his body bounces between cars like a ragdoll. But that’s not the end of the story, it’s just the beginning. Death arrives at the home of billionaire mogul Bill Parrish (Anthony Hopkins) in the form of the unnamed Pitt character, and he has a pitch: As long as Bill guides Death (given the moniker “Joe Black”) around Earth, Bill won’t die. Pitt plays Joe Black as a blank creation, an understandable approach to a character who is meant to be inscrutable and unfamiliar with the particulars of humanity. Unfortunately, it leads to a calculated performance. But the main problem, in the end, is the movie’s ridiculousness, which no amount of star wattage can sell.

32. Snatch (2000)

Watching Guy Ritchie’s interminable, testosterone-heavy crime comedy was a test of my patience. Pitt is clearly having fun playing Mickey, an Irish Traveller and bare-knuckle boxing one-punch champion. But the film’s running joke about not understanding his accent wears thin, quickly. Luckily, he has a spunkiness that offsets things, at least in a few moments — but not enough of them.

31. 12 Years a Slave (2013)

Steve McQueen’s gut–wrenching 12 Years a Slave finds Brad Pitt, who also produced the film under his Plan B shingle, cast as the one good white person who recognizes and calls attention to the brutality he witnesses on a plantation. Pitt’s producing work in the last decade has been defined by bold choices, many of which explore black life in various contexts (see Moonlight and last year’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco), suggesting that he walks the walk when it comes to representation. But there’s something unnerving and oddly congratulatory about taking on the role of Canadian day laborer Samuel Bass, who is the key to Solomon Northup’s (Chiwetel Ejiofor) freedom. While the notes of gravity he tries to add to the role don’t quite work, Pitt isn’t terrible here. It’s just memorable for the wrong reasons.

30. The Mexican (2001)

Pitt’s worth as an actor is often not found in films that require him to be the marquee star. Still, his efforts work well enough here in spite of a grating, uneven film. Directed by Gore Verbinski, Pitt plays Jerry, a low-level, bad-luck mob employee in a relationship with Julia Roberts’ shrilly written Samantha. Pitt and Roberts don’t play off each other well, thanks primarily to a flat script that has them stuck in screaming matches. But Pitt at least brings a kooky energy to the character.

29. War Machine (2017)

In David Michod’s loosely factual war satire, Glen McMahon is a four-star general tasked with pulling troops out of Afghanistan who instead does the exact opposite. The character is a caricature from the start. In scene after scene, Pitt feels like he’s making a performance; he never truly lives and breathes. Pitt plays him as a collection of quirks, and the schtick wears out fast.

28. Allied (2016)

At first blush, Allied should be the kind of film that hits my sweet spot: a sweeping World War II romance using Casablanca and London as its backdrop while dealing with the ethical, moral, and romantic complications that comes when two spies undercover fall in love and start a life together. Yet even though it takes cues from films like Casablanca and Now, Voyager (the latter for its costuming specifically), Allied doesn’t have the magic and verve of those films. Part of the problem is the actors behind the two spies in question, Marion Cotillard and Brad Pitt, who have negative chemistry. Chemistry between actors is a dance, and these two can’t agree on the rhythm of this romance. Pitt plays Max Vatan, a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot, with grim conviction, no matter whether the character is supposed to be haunted or happy. As a result, moments like Max’s proposal to Marianne (Coltillard) — “Come to London and be my wife” — land with the same energy as someone pointing out an exit on the freeway. And that’s to say nothing about the movie’s sex scenes, which are some of the most passionless I’ve seen in a long time.

27. Interview With the Vampire (1994)

In the Neil Jordan-directed Anne Rice adaptation, Pitt struggles to convey the regality of his character Louis, a member of the undead sired by Lestat (a career-best, extravagantly demented Tom Cruise). Pitt’s movements come across as stiff, particularly in exposition-filled scenes involving Christian Slater. He’s just trying too hard to capture the slinky malevolence of the vampire and comes across too studied as a result. But there are moments when he does sparkle — namely during an exceedingly homoerotic, angry goodbye to fellow vampire Armand (Antonio Banderas). Cupping Armand’s face, Pitt brims with complication, mixing anger and deep longing as he whispers about refusing to learn his lesson of living without regret. Pitt also plays wonderfully with Kirsten Dunst’s doomed child vampire, Claudia, in scenes that most clearly bring his character into focus.

26. The Big Short (2015)

In Adam McKay’s thinly constructed dramedy exploring the financial crisis, Pitt plays the small supporting role of Ben Rickert, a man who left the financial industry because of his distaste for how things work yet still mentors two men on how to get rich anyway. It’s a muted and ultimately minor performance that gets lost in the film’s chaotically slick stylings.

25. Spy Game (2001)

Directed by Tony Scott, Spy Game is full of the director’s trademarks — fast cuts, garish filters, and unrelenting energy. Pitt plays Tom Bishop, a CIA asset mentored by Nathan Muir (Robert Redford). Nathan is about to retire, until he hears about Bishop’s capture and imprisonment in China and does everything he can to save Bishop. Pitt plays off Redford (an actor he’s often compared to, both in terms of looks and leading-man charisma) exceedingly well as the young upstart, resulting in an amiable chemistry. Good, but not essential.

24. Thelma & Louise (1991)

What is the alchemy behind a star-making turn? Charisma, of course. Timing, definitely. But perhaps most importantly, a sense of contradiction that audiences are drawn to and want to solve. For Pitt, once he found his standing as an actor, moving beyond the stilted performances of his early years, the contradiction lies in how his sunny good looks hide the remoteness in his characters. In Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise, you catch merely a whisper of this, but it’s there as he plays J.D., the slippery criminal with a downhome drawl that becomes the object of desire for the camera and Geena Davis. Pitt is immediately magnetic.

23. Troy (2004)

In writer David Benioff and director Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy, an exceedingly buff Brad Pitt plays the infamous warrior Achilles with clear-eyed conviction and undeniable swagger. There’s something alluring in how Pitt plays Achilles, adding touches of cocky humor as he faces the twinned fates in his future: fame and death. His eyes glimmer in a conversation with his mother Thetis (Julie Christie) at the idea of immortality. Those are the good parts, the ones that let you gloss past the scenes where Pitt becomes overly serious to the point of blandness.

22. The Counselor (2013)

In Ridley Scott’s wild and wildly uneven potboiler The Counselor, Pitt plays Westray, a criminal associate who warns the titular character (played by Michael Fassbender) of getting involved with the Mexican cartel. Pitt lends the character a slippery quality that makes you lean in closer, wanting to learn more and untangle the practiced nature of his charm.

21. Legends of the Fall (1994)

Edward Zwick’s Legends of the Fall is the kind of overwrought Hollywood melodrama you either love or you don’t. I have a fondness for tales that sweep through time, document the changes of a specific place (rural Montana), and chart a family along the way (headed here by a patriarch/rancher/war veteran played by Anthony Hopkins). In Legends, Pitt plays the middle son and brooding romantic hero, Tristan. In his hands, he’s wild, golden, immensely magnetic. In moments when his character grieves — like when he cuts out his dead brother’s heart on the battlefield in order to bring a part of home to be buried — his wails feel forced, too grand for a scene that demands nuance. He’s best in quieter moments, when romance is just out of reach, or with a stare into the distance that silently communicates just how haunted his character is by his brother’s passing. It’s a reminder that as Pitt became a star, he could rely on his power to enchant.

20. A River Runs Through It (1992)

Set in the glorious nature of Missoula, Montana, A River Runs Through It details the coming-of-age of a Presbytarian minister’s two very different sons — the studious, calm Norman (Craig Sheffer) and the troubled and talented fly fisherman/journalist Paul Maclean (Pitt) — through a changing world than runs from World War I to the Prohibition era. Pitt is tender and complex here. There’s a scene in which Paul regales his family around the dinner table with a story about President Calvin Coolidge. He gives the story a gentle buildup, injecting each moment with charm before using it to steamroll his mother’s worry about how he spends his nights. Pitt complicates the moment by turning his sunny disposition into something darker and more hurtful. That broad smile never leaves his face, and we learn how charisma can be a weapon.

19. Babel (2006)

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 2006 film spans the globe with interconnected storylines, one of which calls on Pitt to play a man hollowed by tragedy. Richard (Pitt) goes to Morocco with his wife, Susan (Cate Blanchett), in order to heal and find solace after the death of their child, which has deeply strained their marriage. Pitt is asked to play a few notes — worn down, tender, frustrated — which he does with grace. It’s a considerable portrait, with Pitt’s furrowed brows and tired eyes communicating a world of hurt.

18. Fury (2014)

It’s spring of 1945. A charred battlefield housing corpses and tanks lies still as a German officer on horseback surveys the wreckage. The quiet is suddenly interrupted when Don “Wardaddy” Collier (Pitt) leaps from a tank, stabbing the German officer in the eye with matter-of-fact precision before he gently releases the horse into the wild. Don is exactly the kind of leader you’d expect to helm the ragtag group at the center of this grimly masculine David Ayer war drama. There’s rough masculine intimacy and all the requisite war-drama shades of vulnerability. One of the better parts of the film, though, is watching the tension rise in Pitt during a fraught meal in the German home of two women. The tension in his performance is quiet first before it consumes the entire scene, making it feel claustrophobic. It’s a remarkable example of how specific performance decisions — a tightened jaw, hunched posture — can shift the mood of an entire scene.

17. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

For such a sweeping, fantastical film, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is remarkably thin in feeling. Rarely does it capture the right magical amber energy it’s going for, instead feeling maudlin, lost, even a touch twee — which is odd considering the usual force of David Fincher’s work. Pitt plays Benjamin Button with too light a touch for a character who should be brimming with deep feeling. (He earned an Oscar nomination for Best Actor for the role.) He has a soft chemistry with Cate Blanchett, but it’s not passionate or deep enough to sell the movie’s key romance. It’s an okay performance in an okay film that works in fits and starts.

16. Killing Them Softly (2012)

Trying to find the truth of a performance is sometimes exceedingly difficult when the work is so subtle. In Killing Them Softly — Andrew Dominik’s machismo–heavy, sweat–drenched noir set against the backdrop of the financial crisis and presidential campaign of 2008 — the truth of Pitt’s performance as mob enforcer Jackie is in his gaze. For most of the film, Jackie is seen talking in rundown bars, empty restaurants, corner diners, the passenger seat of cars. Pitt makes these scenes magnetic simply by the way he surveys a room. He isn’t so much a cool operator as a cold figure who deploys violence with professional precision. The best moments come when he’s playing off James Gandolfini’s Mickey, requiring Pitt to do more listening than speaking, letting the audience in on what Jackie is thinking without saying a word.

15. True Romance (1993)

In this neo-noir penned by Quentin Tarantino and directed by Tony Scott, Pitt plays the small role of Floyd, a stoner and roomate to Dick (Michael Rappaport). His voice, a slow, lackadaisical lilt, is hilarious in the few scenes he’s in. Just listen to his sharp “Oh” in the face of a cocked gun, the urgency humorously pulling the character out of his weed-laced stupor. It’s a master class in how to make a memorable turn with little material.

14. 12 Monkeys (1995)

What intrigues me about Pitt’s performance in 12 Monkeys is the energy it takes to pull off this perpetual unraveling. In the apocalyptic Terry Gillam picture, Pitt is supporting character Jeffrey Goines, a belligerent, manic motormouth. His body is rangey and constantly moving. Every decision is designed to keep the audience at a distance rather than draw them closer. The performance earned Pitt a Best Supporting Actor nomination at the Oscars and a win at the Golden Globes. I can see why — it’s a wild, oxygen-stealing performance that feels potently different than Pitt’s prior work (although one could draw a line between this and Kalifornia). Rewatching the film, Pitt clearly has a pull, but it also feels a touch too performative.

13. Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005)

Mr. & Mrs. Smith is the perfect hangover movie. Silly and simple, it doesn’t take itself too seriously, nor does it have much to offer beyond the central thrill of watching Pitt and Angelina Jolie play a married couple who also happen to be assassins on opposing sides. Pitt isn’t always at his best when asked to be a Movie Star in big bold letters, but here he’s cocky, loose, and utterly beguiling. The chemistry between him and Jolie is electric. It’s certainly not one of Pitt’s most layered performances, but what can I say? Sometimes you just want to have fun at the movies.

12. Inglourious Basterds (2009)

In this collaboration with Quentin Tarantino, Pitt doesn’t play a character so much as a broad, larger-than-life caricature. While he only plays a few notes, he hits them so beautifully and with such force you can’t help but be dazzled. Lt. Aldo Raine is a downhome boy from Tennessee, complete with an arch southern accent, who chomps down words with derangement. Pitt makes a meal of this part, imbuing the character with a cocksure blend of confidence and menace without ever losing the essential humor of the whole thing.

11. Ocean’s Eleven (2002), Ocean’s Twelve (2004), Ocean’s Thirteen (2007)

Brad Pitt’s unflappable cool as Rusty Ryan is simply a pleasure to watch. One of the fun things about the performances is that Pitt is constantly eating (something that runs through his career if you keep an eye out). The Ocean’s films represent Pitt leaning most into his movie-star qualities: laid-back demeanor, relaxation at the pitch of luxury, that bright smile. Crucially, it’s in an ensemble, not a lead role, that he was able to best utilize those qualities.

10. Seven (1995)

In his first collaboration with director David Fincher, Pitt seemingly pales in comparison to the rich, layered work Morgan Freeman is doing. But Pitt is vital to the film, a necessary balance in this two-hander about a grizzled veteran on the verge of retirement and a hot-headed upstart detective who is unaware of just how much he has left to learn. As Detective David Mills, Pitt is a remarkable study in frustration and the ways men are fueled by unhealthy emotions — in this case, his anger.

Pitt elegantly brings Mills to life in the movie’s quieter scenes: eating Lays with his feet up in a library, or tilting back in his chair as if falling were an impossibility. But, of course, the movie takes a turn, and Pitt is ready for the moment. His infamous exclamation at the end of the film (“What’s in the box?”) has been endlessly parodied and joked about since, but forget all that and revisit it. Watch realization bloom across Pitt’s face as John Doe (Kevin Spacey) speaks, and his eyes glaze in anger. He’s best without words here, contorting in pain in the back of a cop car as the enormity of the horror becomes devastating.

9. Kalifornia (1993)

Dominic Sena’s 1993 thriller Kalifornia, contains one of Pitt’s greatest physical performances. The plot: Brian Kessler (David Duchovny) is a writer working on a book about serials killers with his forthright photographer girlfriend Carrie (Michelle Forbes); he has plans to road trip across the country, visiting various infamous murder sites, before relocating to California. Brian advertises a ride share whose only respondents are Early Grayce (Pitt), a chaotic psychopath killer, and his naïve girlfriend, Adele (Juliette Lewis).

Brian is seduced by Early’s outlook, and it’s no wonder: Pitt is mesmerizing. His Early doesn’t walk. He stalks, lurches, stomps. He grins like a dog baring its teeth. Pitt’s voice is one of his most effective tools here. He growls, even when pleased; he chops off the end of words; he barks, snorts, spits, giggles, and rudely takes up sonic space with unrepentant delight, forcing people to take notice. Violence sparks easily in Early, and he gives into it with abandon, without regret or posturing. Pitt’s tongue — which hangs from the side of his lips — tells a story all its own about Early’s insatiable hunger. The film is quick to describe Adele and Early as “white trash,” but Pitt never condescends to his character as he carefully charts his anger and prejudice.

8. Burn After Reading (2008)

In this Coen brothers film, Pitt offers a performance full of both beautiful sincerity and near-slapstick comedic heights. Chad Feldheimer is a doofus trainer who is in over his head, but Pitt definitely is not: He plays Feldheimer with gusto, showing off his ability to take his physical talents to hilarious ends. His energy is wild and broad. In its most pleasurable moments, Pitt plays Chad as someone acting how he thinks someone in espionage would act — which, obviously, means narrowing his eyes and dropping his voice. It’s all foolish, of course. It’s in Pitt’s small flourishes — chewing on gum and straws with a glazed look — that makes it clear what Chad is really thinking: Nothing at all.

7. Fight Club (1999)

In a Film Comment column, critic Sheila O’Malley wrote about the phenomenon of “back-ting,” in which an actor is turned away from the audience. “An old friend of mine came up with a term for moments like Charles Lane’s in Sybil: ‘Back-ting.’ To this day, I am fascinated by moments when actors turn their backs on the camera. It is actor as storyteller, actor as auteur.”

Rewatching Fincher’s second collaboration with Pitt, Fight Club, I was surprised by just how many moments of back-ting there were, the most mesmerizing of which occurs in an early scene, when the eponymous club is just starting to gain traction. Tyler Durden (Pitt) is simply walking through a bar to the tune of “Going Out West” by Tom Waits. But in this singular moment, we can see, even from behind, that Tyler has what the unnamed narrator played by Edward Norton lacks: unbridled, unending confidence and a clarity of self. “All the ways you wish you could be, that’s me,” Tyler says later, sitting with the stillness of a coiled snake that’s waiting to strike.

Pitt’s mythic presence in Fight Club is almost overbearing, hard to look away from but beckoning all the same. A lot can be written about how much Durden is informed by Michael Kaplan’s costuming, and for sure, the ostentatious clothes are a key part of the character. But it’s Pitt who makes sure his problematic icon remains fascinating when he’s shirtless and covered in blood, all fists and fire.

6. By the Sea (2015)

In Angelina Jolie’s directorial work By the Sea, Pitt and Jolie play a couple in a disintegrating marriage who go to the coast of France to heal themselves, but instead start spying on their neighbors through a hole in the wall. But the plot isn’t the point. The film is a mood poem about desire, longing, the body, and the personas we create for ourselves. Pitt’s spikes his usual persona with an element of sloppiness. He’s alcohol-soaked and full of yearning. In one of the movie’s best moments, Pitt walks into the bathroom to talk to Jolie. “You look beautiful laying there. Maybe I don’t say that enough,” he tells her, his eyes downcast, wounded. This is a man brought low, hungry for affection, for a healing in his marriage, and his every gesture radiates with sorrow.

5. Moneyball (2011)

Manuela Lazic wrote in the Ringer, “Pitt approaches acting as an exercise in looseness; he seems to be testing just how unforced he can be while following the script he’s been given.” This is indeed clear in his work, but part of his power is the mystery that lurks under his surface. This is evident in Moneyball, where he plays Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane. As Beane, Pitt carries tension in his jaw and looseness in the rest of his body. An air of regret hangs around him. Whatever he’s repressing, it’s always close to bursting through the surface: At one point, he turns over a desk with the casualness of brushing hair out of his eyes. (It should also be noted that this is another film where Pitt eats a lot, a cinematic habit that cleverly punctures the Brad Pitt-ness off his more un-Pitt-like characters.) Pitt delivers a complicated, physically precise performance that illustrates what he’s so often best at: exploring masculinity at the pitch of crisis.

4. The Tree of Life (2011)

Terrence Malick’s lyrical drama Tree of Life — undoubtedly one of Pitt’s most finely wrought performances — asks the actor to channel a specific brand of mid-century white masculinity: stern, focused, controlling, and bubbling with misplaced rage. Pitt obliges with eloquent precision. He has an immense understanding of the character. Listen to the ferocity in his voice as he yells “Hit me” to one of his sons with an unblinking gaze. The scenes between him and Jessica Chastain are sharp enough to draw blood. In one instance, when a fight between them gets physical, Pitt wraps his arms around her, preventing her from moving. Their bodies say what remains unspoken in the film.

Given Malick’s improvisational style, I wondered if Pitt came up with certain touches himself, like when O’Brien casually withholds a tip from a waitress, teasing her by keeping it out of reach. It wouldn’t be a surprise if he did. By this point in his career, Pitt had grown more assured, expending less energy to yield greater impact, and in Tree of Life, he shows off his increasing command as an actor.

3. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

In Tarantino’s grand, detailed, warm treatise on 1969 and old Hollywood, Pitt is a revelation. He plays Cliff Booth, the stuntman and right-hand man to Leonardo DiCaprio’s failing actor Rick Dalton. It’s the kind of performance that looks effortless, a hard feat in and of itself, but stays in your mind (and potentially in the minds of Oscar voters). When Pitt isn’t onscreen, you yearn to see him. One of the things that makes Pitt such an intriguing movie star is that he doesn’t run from his beauty the way actors like Jake Gyllenhaal and Christian Bale tend to. He revels in it. This is true throughout Once Upon a Time, in which it seems he is bending the light toward him.

Cliff Booth’s life might be routine, but he moves into spaces where the ideologies represented in the film — about nostalgia, history, cultural and personal mythologies, and Hollywood itself — come to a head. Pitt knows that Cliff is a complicated man. His outwardly chill demeanor belies a pool of anger, clear in the film’s end but also hinted at earlier on, in a controversial scene with his wife. I keep coming back to this performance, hoping to decipher what is so effective. But this is the power of a movie star: to heighten the mundane — walking across an empty lot, eating macaroni and cheese from the box in your small trailer, smoking a cigarette — into something of elegant, mythic beauty.

2. Ad Astra (2019)

Every actor has a story. I’m not talking about the origin stories that bring them to our screens. I’m talking about the stories a star tells us through their work, about how we move through the world. Pitt works primarily in three modes: chill, wacky and arch, and matinee idol. He’s most impactful when he’s playing characters of incredible self-possession and prickly charm (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood; Moneyball) or men who are called to navigate fissured emotions they can no longer ignore (The Tree of Life). In James Gray’s Ad Astra, these approaches are synthesized into a career-best performance.

Roy McBride — a near-future astronaut on a dangerous mission that involves searching the cosmos for his missing father (Tommy Lee Jones) — is a tragedy. On the surface he’s in control, exceedingly calm under pressure, all translated through the still, closed-off physicality Pitt grants the character. But there are cracks from the beginning. When McBride is asked about his father in an early scene, Pitt holds onto the pause long enough to fill it with yearning. His eyes grow a shade tenser, and the depth of his loss becomes unmistakable.

Gray relies on tight closeups of Pitt’s face to communicate the film’s emotional arc; the actor’s visage becomes a textured landscape of its own, from the way he blinks to how he perpetually fights back tears. Pay attention to how his breathing moves from steady to ragged, unbalanced by the revelations concerning his father. It’s a fascinating contradiction of a performance, a comment on the ways a patriarchal society demands men to compartmentalize their emotions.

1. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

In Andrew Dominik’s poetic, crisp The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Pitt hones the full force of his abilities as an actor, utilizing his lupine grace and reserves of cool to give a multifaceted, towering performance. It’s also a performance that — aided by the narrative about the famed outlaw and Roger Deakins’s haunting cinematography — invites us to consider notions of celebrity, masculinity, and beauty; what it means for a star to transform; and the stories the human body can tell. Pitt’s excellence becomes evident quickly: Early in the film, there’s a shot in which Jesse James cuts through a dusty town. In the fluid movement of his walk and the posture of his back, we can see the power in the character.

The movie’s consideration of celebrity and obsession slyly makes Pitt an object of desire, allowing us to consider his persona as a star — calm, collected, sexy, and sunshine bright, yet, again, with suggestions of something hidden roiling beneath the surface. In his essay collection The Devil Finds Work, James Baldwin wrote about the stars of classic Hollywood, like Humphrey Bogart and Bette Davis: “One does not go to see them act: one goes to watch them be.” Watching Pitt, this still holds true. There are moments when Jesse James feels mythic — his silhouette against the light and smoke of an incoming train, for example — that still have the power to stun me, even after seeing the film several times.

What makes this role so fascinating is how it both plays with his movie-star aura and pushes against it. Pitt plays into his character’s harsh masculinity by highlighting its callousness—just watch the way his eyes narrow with greed or brighten with the potential for violence. He gives Jesse James a steady, even steely quality. (His command of stillness is in even sharper relief when he’s next to the jittery affectations of Casey Affleck’s Robert Ford.) But he also consciously uses his beauty to enchant and ensnare us. There’s a dancelike quality to the way he moves his body, and sequences where Pitt melts his hardened charisma: like an aching scene when he’s alone, his fingers running through wheat in an open field. It’s the kind of performance that argues that these kind of stars are doing more than just being — they’re actively working with how they’re perceived in the world.

There are some stars you turn to to see life reflected at you. There are others still, like Pitt, you turn to to see how much more beautiful and grand life, and the human body, can be.